Antony Cairns (b. 1980) has been taking photographs since the age of 15 and continues finding himself mesmerized by the mysteries of the ever-evolving medium and ever-changing faces of metropolises. His ongoing project ‘CTY’ (an abbreviation of ‘city’) sees the expansion of his oeuvre and is a testimony of his devotion to his subject: urban life and urbanisation. His muse has taken him all around the world, from his home London to Las Vegas, Tokyo and Osaka. The large body of work consists of original 35mm black and white film transparencies which he reversal develops into positives. The images not only function as archival documents of architectural, often skeletal structures and topographically built-up environments, but also as visual representations of what a city is and means in a more philosophical sense, and how it is in constant change.

Interested in how photography can be used to define the character of a place, Cairns began recording the fluctuations he noticed within the landscape; the deterioration of buildings and the sudden rise of new ones — all to capture the ambience and atmosphere.

Traditionally trained at the London College of Printing towards the end of the 1990s, his creative practice has remained rooted in analogue-based processes. Cairns recycles and re-uses forgotten, discarded or outmoded equipment and technologies. Like a magician and lab technician, he pushes the boundaries of what is possible under red light, performing darkroom tricks and producing chemical reactions which make his visionary cityscapes appear out of thin air. He regularly finds himself becoming spellbound by the imperfections and oddities of each distinctive method. Typically distorted, blurred, grainy, washed out or shrouded in darkness, his work has a supernatural feel.

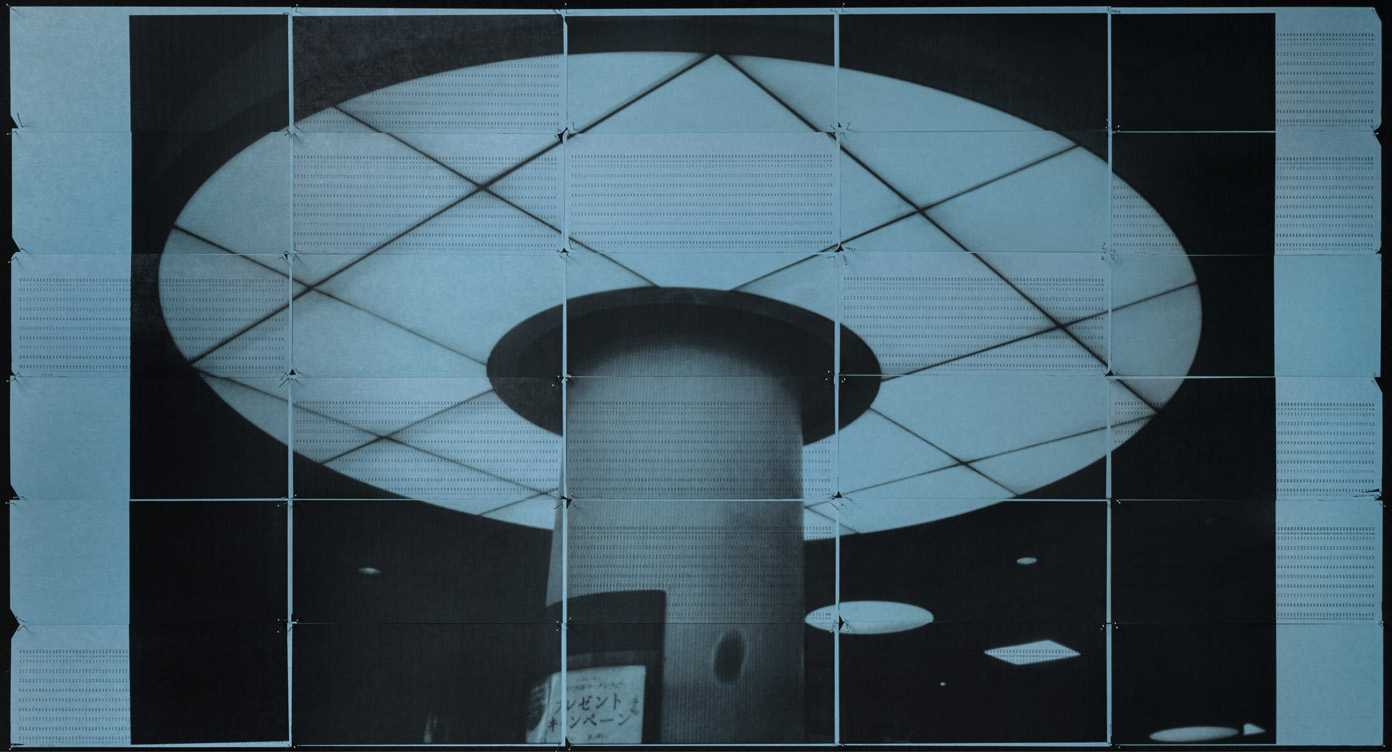

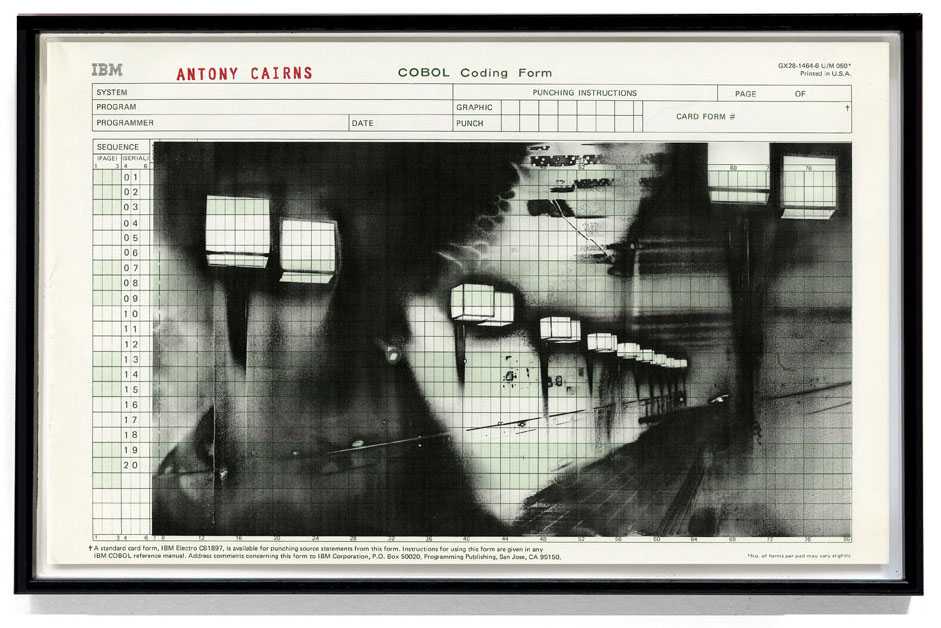

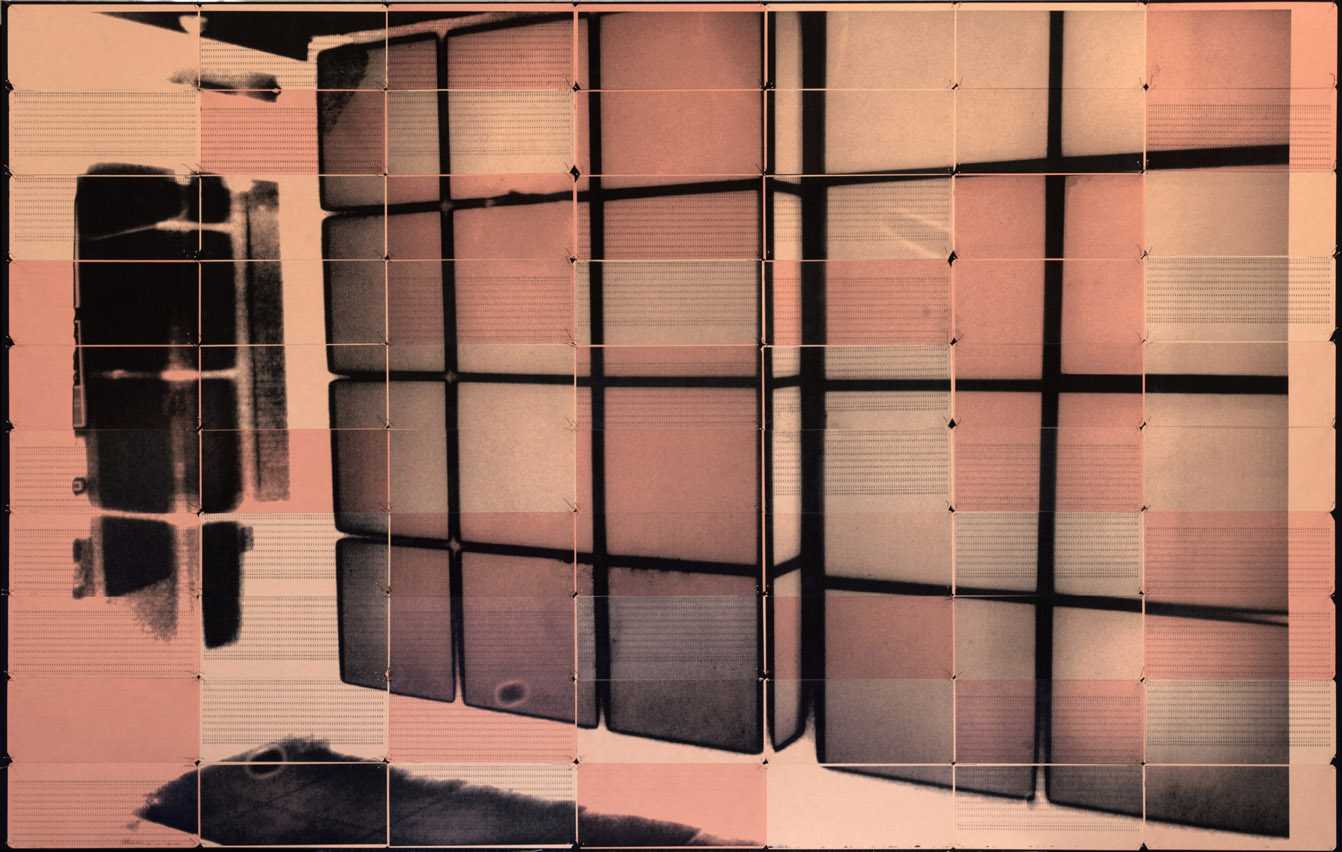

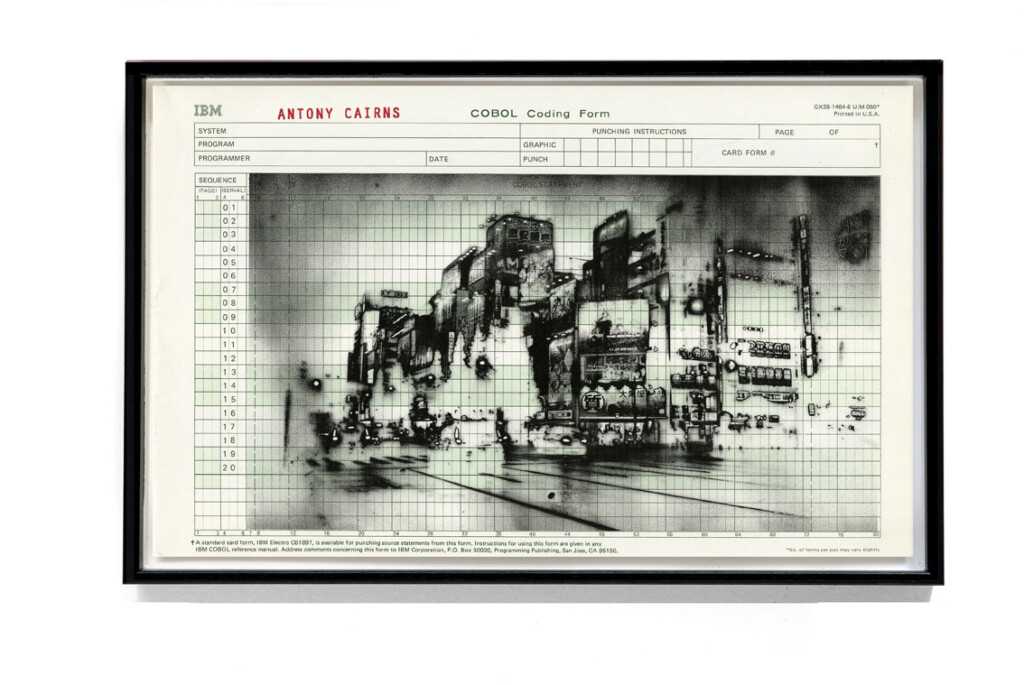

For exhibition display, Cairns reproduces a selection of images from his portfolio in a variety of unexpected and unique ways, creating artworks that span across photography, installation and sculpture. He has printed directly onto vintage Cobol coding forms, IBM decision tables and computer punch cards (pieces of stiff paper where holes can be punched into), visually embedding his work in an antiquated digital language. He also uploads scans onto Electronic Ink Silicon screens, transfixing them as jpeg files with abstracted aesthetics that address notions of transformation and modification.

GUP was fortunate enough to discover more about the thought process behind Cairns’ intriguing works from the multi-faceted artist himself.

To start off, where did your fascination with urbanisation come from? Many of your projects are made in big cities like London (where you grew up), New York and Los Angeles. What is it about these extremely metropolitan places that urges your artistic instinct? When and how did you start incorporating this interest into your creative practice?

I studied photography from an early age and soon started leaning towards a more focused interest on the imagery of the city. A fascination with how photography can portray a city grew over time, photobooks like Weegee’s ‘Naked City’ were really inspiring me to also use photography to tell the story of the metropolis that I lived in. From early on I used London as my focus when creating projects. I initially liked photographing historical parts of the city that were disappearing due to regeneration and gentrification, like closed-down pubs and vintage shops. On returning to these places, I realised that many of them were being replaced by conglomerate mega-complexes, so I moved more into trying to photograph the future of the city; what the urban landscape will look like or wants to look like. Later I took my same ideology to other places around the globe that matched the intensity of London as an urban centre.

Your cityscapes are typically devoid of three elements: people, daylight and colour. Why?

I made a conscious decision to shoot at night, often late at night, only using the available light and the flash of a small electronic camera. This in some ways accounts for the lack of people I suppose, but it is a deliberate choice as I am making imagery of the city and its infrastructure. I like to concentrate my audiences’ view on these elements. Also, I love the electric and digital feeling of the city at night, the neon haze and the fluorescent flickering. A megalopolis is just that, the city never sleeps, it is always there surrounding you. I do shoot mainly in black and white, but the reproductions of the original negatives often have elements that add colour to the works, and I sometimes also make hand colour pieces. For the last 6 years, I have printed onto vintage coloured IBM computer punch cards which I use to create large scale image compositions and montages.

Your practical approach is rooted in chemical-based techniques but combines the analogue and traditional with outmoded and modern forms of technology. Could you elaborate on your reasons for employing all these evolutionary configurations of the medium?

Overall, I am intrigued by the reproductive nature of photography and its continual link to technology. My interest lies within wanting to have a vast understanding of the history of the medium. This knowledge I can then use to choose the best type of photographic technology to create art pieces that fit the aesthetic I am looking for. I want my artworks to show the viewer the more obscure ways of presenting photographs.

How do you prepare your works for display? And how do you decide what form of presentation or printing technique best suits and compliments each piece?

When I marry printing technique to imagery it is to create a presentation that enhances the artwork. For instance, when I upload images onto an Electronic Ink screen and encase that screen in Perspex it is made to create a feeling that the artwork is a digital and photographic relic. There is always a reason to the choices I make.

Your images evoke notions of conventional documentary photography, but with an alternative, sci-fi twist. Do you consider the nature of your pictures to be documentary – also in the sense that they might contain historical value (compared to the more common commissions for artists to ‘map’ certain places/areas in development?)

Yes, I totally feel that they are documents that could be seen as record photographs. It is undeniable that underneath all the layers of abstraction, they are in the end photographs of a place within a city, shot at a certain time. I never add this information to the titles of the work currently though, because I prefer the audience to have their own idea of where and when the photograph was taken and to feel that they are looking at a representation of a city, it does not matter which one.

Do you think that the ominous and dystopian aspects of your works that were produced pre-Covid might now be seen in a new context – considering the anxieties that came to the surface? And if so, could your images add to the understanding of what happened to the world in the last year and a half or so?

I am not sure; I do not see any relationship with my works and the world during a pandemic or post pandemic. The pandemic which is now an endemic is not really in my mind when creating new projects.

Your projects require a lot of travelling, which has been difficult due to Covid restrictions. How has this affected your work mode?

Of course, during Covid, I did not do much shooting or travelling. I said previously in this interview that the city does not sleep, but during the pandemic, I really did not want to go and shoot the city at night. It did not have the same feeling and atmosphere, something was missing. I was lucky actually because in late 2019 I was on a three-month residency in South Korea and Asia, so I made a lot of work there. When lockdowns occurred, I had a lot of material to process and work through.

Finally, are you willing to share anything about your plans for your next project?

I am still working through imagery I shot in Asia just before Covid hit, a lot of the stuff is video works shot on a really quirky piece of film/video history. A PXL 2000 (1986), a video camera that captures black and white video data onto audio cassette tape. The unique footage from this camera will be the material from which I make my next few projects.

Antony Cairns lives and works in London and has been featured in international festivals and institutional exhibitions in Europe, the United States and Japan. His work has been shown at the Recontres d’Arles as part of Arles festival in 2013, at the George Eastman Museum in New York in 2016 and at Tate Modern in 2017. He was awarded the prestigious Hariban Award in 2015, resulting in a residency at the Benrido Collotype atelier in Kyoto. Cairns published a selection of artist books named LDN (2010), LPT (2012), OCS (2016), as well as work created using translucent silver gelatine films applied directly to sheets of aluminium in LDN2 (2013), LDN3 (2014). He also made experimental pieces with electronic ink for LDN EI (2015), both in working electronic Ink readers, hacked to contain his complete work and on their extracted frozen screens; strange distant descendants of the daguerreotype TYO2 (2017).