Stephen Gill (b. 1971, Bristol) is a British conceptual image maker who mainly draws inspiration from his immediate surroundings and constantly pushes the limits of the photographic medium to catalyze a unique, visual language in which documentary coincides with chance, experimentation and intervention. Having built his career upon an ethos of creative enterprise, Gill as an established photographer, has furthermore been described as an anthropologist, sociologist, archivist and alchemist. His signature style of combining both his artistic and technical abilities has amounted to a notably diverse and distinctive oeuvre of photographic burials, tangible collages, submerged pictorial worlds, and in-camera photograms where objects appear simultaneously both behind and in front of the lens. Surreal and poeticised, his multi-layered works continue to disorientate the viewer about scale and subject matter through curious juxtapositions between fabrication and materiality — ultimately to heighten and elucidate the spirit of a place, not only in terms of what it looks like, but also how it feels.

In 1992 Gill enrolled on his first photography course in Bristol, capturing the streets and cityscapes around him. In 1985 he visited Arnolfini — a public space for contemporary arts that has been woven into the fabric of Bristol since 1961 — and was inspired by the exhibition ‘Graffiti Art’. Now, a few decades later, Gill returns to his place of birth with a retrospective showcase of numerous bodies of his own work, including previously un-exhibited and new projects such as his latest series and book ‘Please Notify the Sun’, as well as works from his renowned back catalogue. Informed by the artist’s extensive and meticulously ordered archive, the exhibition celebrates thirty years of extraordinary practice and forms part of Arnolfini’s 60th anniversary programme and the inaugural Bristol Photo Festival.

GUP was fortunate enough to discover more about the artist who leads us through the inner city life of East London to the rural surroundings amidst the Swedish countryside.

To me your works are kinds of catalogues and accumulations of things and forms of life, which hold every little detail and fragment of the world. Especially the photographs from ‘Talking to Ants’ and ‘Outside In’ — where you invite objects and insects into the body of your camera — are more like photographic studies. When did you become fascinated with the biological and what is it about the micro and macro world that interests you?

Without question, it all stemmed from my early childhood. I became interested in photography because of an initial obsession with collecting insects and bits of pond life that I inspected under my microscope. It was like a world within a world, or a world within a drop of water. As a child your imagination spirals and this idea of diving into these worlds that you invent or encounter was very exciting. Even now in my adult life, my work is made with a similar mindset. ‘Talking to Ants’ especially, was completely going back to what I would do as a child: to go into these worlds and spent a lot of time there. It is many things, but also an attempt to try and grasp what a place feels like, using photography not just as a descriptive tool. As much as I love photography’s great descriptive strengths, I started to kind of abandon them since 2005. There are a few series where I started to rely less on information and more on the feeling of a place. Sometimes I would try to let the place itself inform the work and guide me. Deliberately having less control, I find that so exciting.

Your work developed from straightforward depictions of places into more abstracted and experimental interpretations by literally bringing the subjects inside the frame as a way of collaborating with your surroundings. What caused this shift in your engagement with your surroundings? Could you elaborate on this concept of letting a place guide your work?

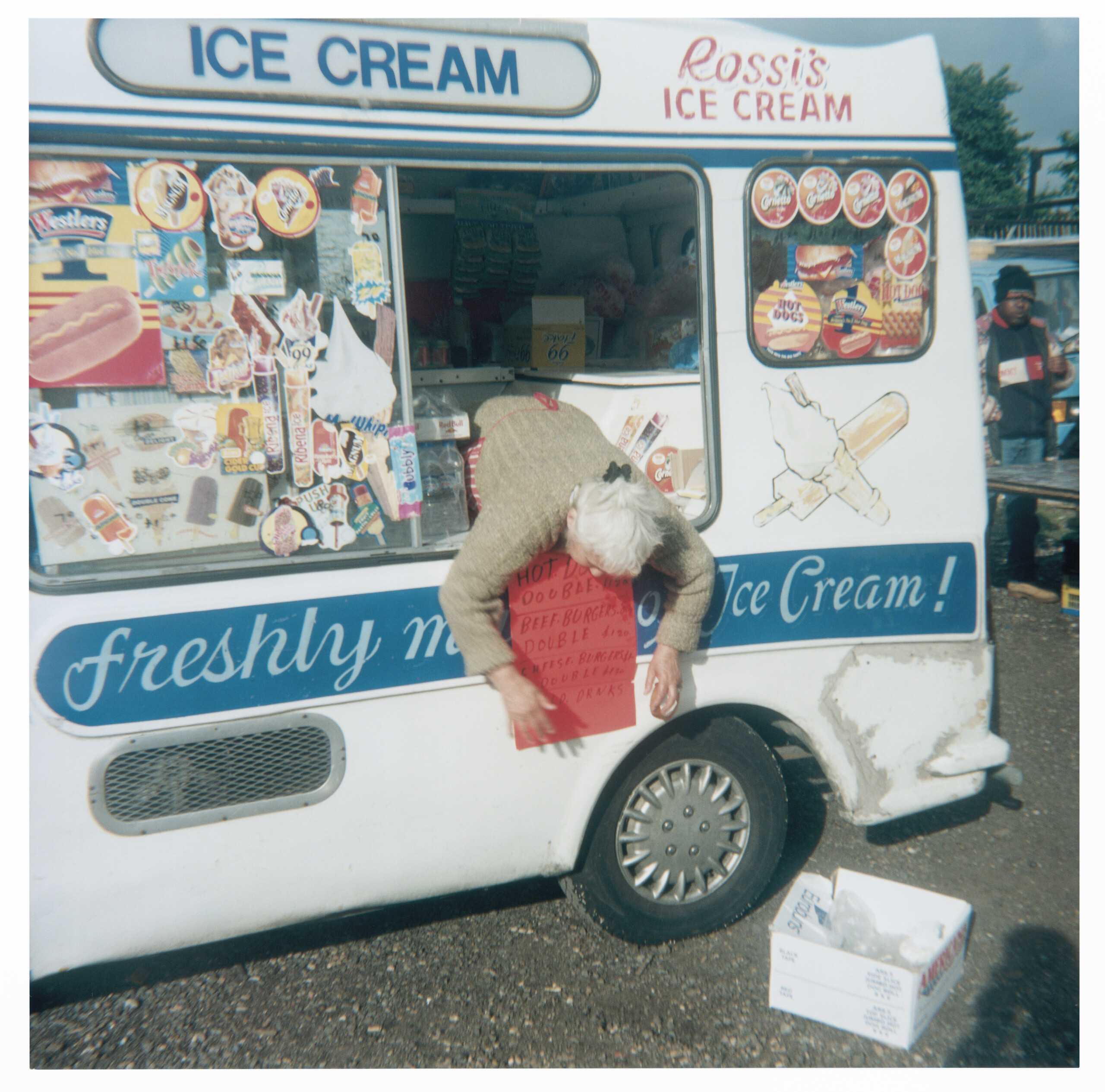

It was like I was hitting a glass wall, where you feel you pushed yourself and pushed your photography to a limit. Photography kind of suffocates, restricts and suppresses the subject. That was the big worry for me, this holding down the subject by photographing it, this sense of limitation. I do not mean to talk bad about the medium, but I just felt there were so many more possibilities, and when I first started to explore that, it was like opening little doors and walking through them. You just have to get to the other side of these technical parameters; the camera, lenses and optics. I started to think about how I could help the subject to speak for itself. In 2001 when I was photographing in Hackney Wick, I used a plastic camera with a plastic lens, and even though the information was denied or kind of tuned down, there was something amazing happening. It all became about capturing the atmosphere. I still see it as documentary in a way, but it is about wondering what a place feels like, over or above what it looks like. It embodies the subject more, but it is partly what you are bringing to it with your mind too.

It is kind of ironic, because you are told to look after your camera, but I was at a point where I was also partly running away from photography. I was so tired of it, I pushed it as far as I could. I was never really precious about cameras I suppose, so I destroyed quite a lot of cameras in the process over 5 years. I was taking them apart and repairing some old ones with broken bits. I was making and repairing them as I went along. I remember putting ice in the camera, and having to work quickly before the ice started melting. I did this between 2009-2013. I never considered that this concept and way of working was a niche approach or a gap in the market. It was always completely personal as I felt like I had exhausted the medium or it had exhausted me. I wanted to respond to a lot of things, so it was about pushing the medium, not based on aesthetic. Ultimately it was about grappling to find a way to articulate certain things.

You once described your work as where “intentions collide with chance”. To what extent does your practice rely on chance?

In the past 16 years I kind of thought along those lines. The danger with photography is that sometimes the photographer projects so much of what is in their head onto the subject, that they are not really giving it a chance to breathe or speak for itself. Photography has this terrible habit of imposing ideas and rejecting so much that is already out there. I was always thinking of this balance between intentions and chance. You can steer something but you do not know exactly how it is going to land. You are composing your rectangle, which gives slight control, but of course you do not know exactly what is going to happen within that rectangle. I love thinking about that exact point where the two meet and collide. As I have gotten older, I have really enjoyed this idea of stepping backwards, taking as many steps backwards as I can, and encouraging the subject to take a step forward. You are orchestrating the picture, but in some cases you are not actually even there. In ‘The Pillar’ I managed to finally step out all together as the birds took the pictures themselves.

I have noticed you tend to think and work a lot in series and collections too – your earlier works ‘Cash Points’, ‘Billboards’, ‘Bridges’ and ‘Roadworks’, to name a few. The way you approach topics as inventories reminded me a lot of Ed Ruscha, who also picks simple subjects like swimming pools and parking lots, and then goes out and photographs them. Could you tell me about this methodology of archiving and collecting? And was Ruscha indeed a source of inspiration for you or are there other artists who influenced you in this process?

I have always been interested in this detached, descriptive way of taking pictures — not stylistic, not about me or my signature style. I would say if anyone was an influence to me when I was younger, it was August Sander and his super descriptive typologies. Now I understand in my adult life as well, another reason why I did this. I only recently realised this. In London where I lived for 20 years, it is visually so noisy, a constant visual bombardment. As much as I had such a strong desire to make work in London, I thought I could not possibly get my teeth into everything that was going on in my mind. I decided my only way into London was to photograph things that interested me or that I wanted to describe or explore, or make a study of, or respond to in some way. I had to tune into these very narrow subject parameters, like you said ‘Cash Points’ or ‘Billboards‘. That was a way to explore things that interested me but in great depth. It also says a lot about what I was not photographing, and in a way, I was using photography to filter out everything else so I could concentrate just on one thing. As I grew older, I became less scared of the visual chaos and noise in London and started to get more confident, making bodies of work that were not conceptual or with narrow subject matters, but more geographical. That was so liberating, I became much looser and things went where they wanted to go.

Before you head out to take pictures, do you make a checklist or set yourself a challenge to search for these specific subjects? Or do patterns only start to occur and become realised once you get back to your studio and review what you have shot?

I would already have decided on the subject, I am quite disciplined in that sense. I would rarely work on several series at the same time. The weird thing is, once my mind is tuned into something, that is all I will see, sometimes for months. I think everyone does that, to some extend. We all see what we want to see. For example, if you were thinking of getting a new pair of red shoes or something, you would probably see loads of people wearing them because your mind stirs your vision. I would leave my house or studio, purely with that in mind and just walk for 6 or 8 hours searching. I would never question an idea too much; if it is a good idea, if it will work or if I and other people will like it. I would just do it and get it out of my system. I would also never think of the audience. It was purely the subject that was enough to carry and make the work. At the end I would assemble it and see what it was about.

Besides all manners of things you encounter on your cycles and walks, do you avidly collect anything else?

In London I was constantly picking things up and I have done that all my life really. I have noticed that my daughter does it too, but surely she has not seen me do that. I have such hungry eyes, they just never rest. I would not say it is necessarily collecting, but I do pick stuff up. When I was making ‘Hackney Wick‘ I was gathering objects like flowers that would end up being the ingredients for another series, ‘Hackney Flowers’. With ‘Talking To Ants’ it was the same, just this constant extracting from my surroundings…

A lot of your work is often slightly or even completely out of focus, for example in your series ‘B Sides’ and ‘Coming Up For Air’. Your images are very detailed yet vague and surreal. Are you willing to say anything about how you achieve this effect? And why?

Those are probably one of my favourite series, which I started around 2008. London at the time for me was so overwhelming and I was having lots of exhibitions and producing books. Modern inner city life, wherever you live, is quite intense and I was very sensitive to that. I remember thinking of making a body of work that was not a description of the modern world, but actually a complete reaction to it. Even if the pictures were made in Japan, it definitely is not about Japan, but probably more of a reaction to my life in London at the time. ‘Coming Up For Air’ is so multilayered and means so much to me. I always thought of it like the idea of when you go swimming and you go underwater, that you get that amazing muffled, odd sound. It was almost an attempt to make a photographic equivalent of that murky and muted, elongated sound. Turning the volume right down, so it is just the photograph. I said to a friend of mine: “well, imagine if the photograph was a living thing”. It was this idea of trying to make a picture that just had a pulse, that is just hanging in there as a picture. It is like putting your fingers in your ears and muting this intense life that we are all living. The journey took me to a lot of aquariums, and I realised that when I was leaving the aquariums, I started seeing the human world in the same way as the aquatic. It started to feel like a fictional underwater world, from the fishes’ perspective looking out at us. Perhaps it was like photography as therapy too.

Since moving to Sweden you have further explored your fascination with animals and the natural world. In your more recent series ‘Night Procession’ and ‘The Pillar’ you used special cameras with motion sensors. Could you tell us about the dynamic between you and the animals, and the technicalities of capturing them from such close proximity?

When moving to Sweden, I was not sure if I was either going to stop photography forever or start from zero, from scratch. One thing I always understood is that nature would play a big part in my work. I could see that my imagination would have to work much harder compared to in London, where there is so much going on and the landscape is so visually exciting. I would now have to extract the subject that is there, but cannot always see. When I was first here in Sweden, I would see traces of animals and birds in the morning. I could feel that it was busy, that there was this nocturnal presence. That is what led me to putting cameras in the forest. I thought I would try it as I lived in cities all my life, but I did not want it to be like a project about a person from a city that goes into nature. I did not want to impose my preconceptions onto nature, but let it guide and inform me, and steer the work. You are assembling something in order to allow things to unfold. After a while, even though chance played a big part, there were times where I envisioned things that could happen and I started to become quite accurate, predicting how the animals would behave or where they would be. You get to know and think like the animal. I loved the idea of composing the empty rectangles in daylight, seeing things with clarity and then watching it happen at night.

Talking about your move from the streets of Hackney Wick in London to the Swedish countryside — are there any cultural differences that have influenced or inspired your photography?

My work in London was quite angst-driven. The biggest difference is that the imagination has to work harder here in Sweden, but I like that. It has enabled me to explore things differently. I have become really interested in what we cannot see yet is there.

For your latest series ‘Please Notify the Sun’, you spent 10 weeks scrutinising a single fish which led to incredibly artistic and varied outcomes. How did you prepare for this journey of observation? Did being in lockdown due to the pandemic help you slow down and reflect more on life in general?

I have been thinking about this project for years, but I never had the energy. I was really burnt-out and exhausted, and I did not have the courage to start it. For years, I was sort of assembling what I thought I would need to go on this journey inside the fish, so I would start creating this set-up with lights, which I tested and thought could work as ‘the stage’. I saw it as this big expedition, like going to space or something. Then of course Covid happened and all my exhibitions and trips were cancelled. Even though I was not in the best shape at the time, I thought this was the moment to do it. I cannot travel so I have to travel inside the fish. I went fishing with my kids and eventually caught one. The next day I started the project.

Lastly, photo books are a big part of your career. You have published a vast collection of them under the name of your own publishing imprint Nobody Books, which you founded in 2005. What makes you so passionate about photo books? Do you believe they are the ultimate format for presenting your photography? And if so, why?

When I was younger I used to love picture books and in that sense photo book have always been quite close to my heart. The first ones I published were almost like a vehicle to carry finished bodies of work; to lock them down and incapsulate them. There are so many reasons why I like photography in book form. They are portable, quite democratic and not as expensive as prints. They travel and have their own life. It was really good to make books for me mentally, because it was a sort of closure. When you spent long periods of time immersing yourself in something, it was psychologically really helpful to know when a project was finished or when to bring it to an end, otherwise I would just never stop. When the book was made, it allowed me to move on to the next thing. I never thought my publishing would get so big, so in the end I was a bit scared that the publishing would start to suffocate the art. I have always been careful to keep my bookmaking and work making very separate. I have noticed too, that when you make all these books, people are always seeing things for the first time, even though for you those are projects you made years ago. Making books is like leaving a legacy.

Stephen Gill’s works are held in various private and public collections and have been exhibited internationally, along with his books that are a key aspect to his practice. Some galleries and museums include: London’s National Portrait Gallery, The Victoria and Albert Museum, Tate, Archive of Modern Conflict and The Photographers’ Gallery. Gill has had solo shows at festivals such as Recontres d’Arles, The Toronto photography festival, Festival Images and PHotoEspaña. In Summer 2013 Foam Amsterdam dedicated Gill a big retrospective ‘Best Before End’.

Coming up for Air: Stephen Gill – A Retrospective is on display at Arnolfini from 16 October 2021 to 16 January 2022.