Rebecca Bowring (b. 1985, Switzerland) is a Geneva-based visual artist whose work questions the paradox of time within the medium of photography alongside the materiality of imagery that we create throughout our life. She is a graduate of the Vevey school of photography and of the University of Art and Design (HEAD). Recently, she was awarded the Near. Prize, an annual award providing a financial incentive to encourage production and foster new ideas. This year’s theme was “unspoken”, making Bowring’s project ‘Knowing Thunder Gives Away What Lighting Tries to Hide’ (2020) a perfect fit.

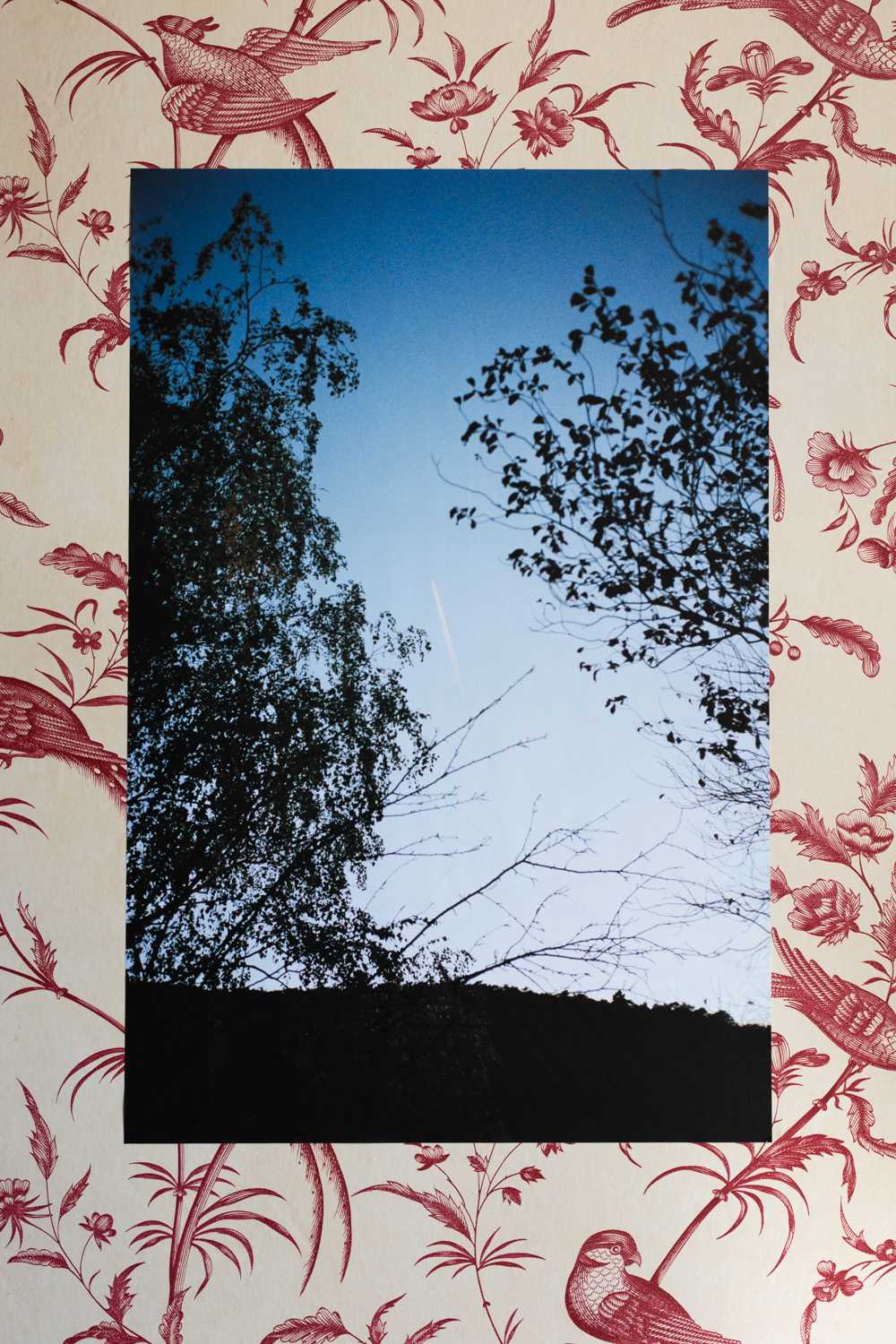

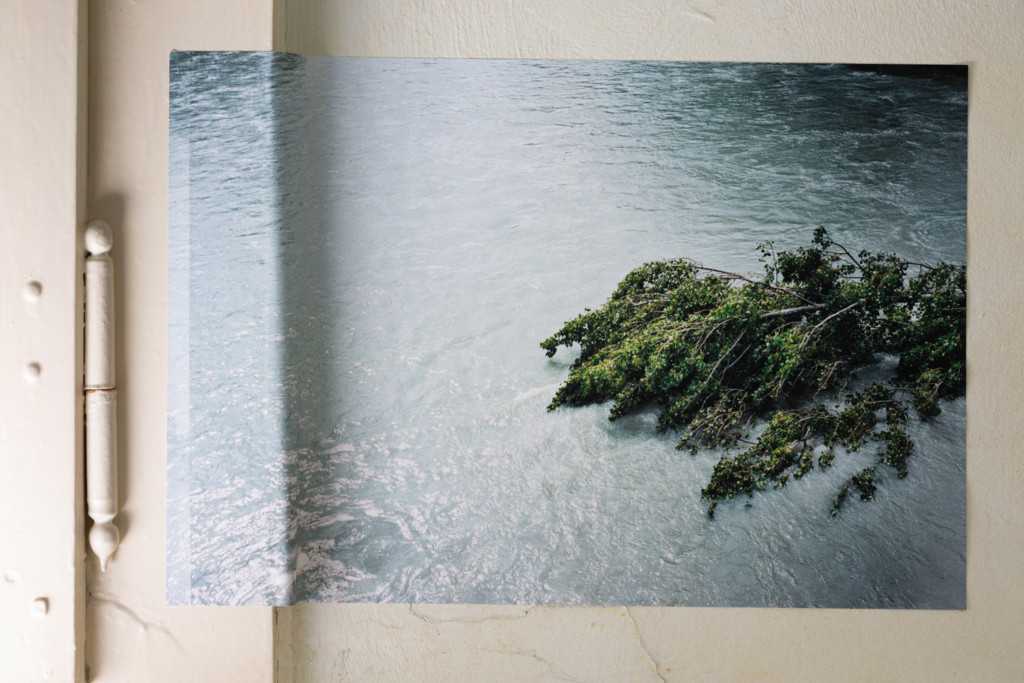

Confinement accompanied by alienation is no stranger to all of us after the outbreak of COVID-19, yet Bowring’s work examines an additional layer, that of domestic violence. Her personal experience is conveyed in the form of escapist landscapes that are mounted as posters in interiors. Serving as both a mental escape for the artist and metaphor for the violence and destruction experienced, Bowring creates a body of work that is soaked in subtle tension, directly piercing her audience.

On the occasion of Bowring’s awarding, we sat together with the artist to discuss her unique approach to the medium.

What was the defining moment when you decided to confront this traumatic experience and started visualizing it?

It was with the familiarity I felt during the first lockdown. The sense of being separated from friends, family, and life as I knew it. It was then that I realised it was all there echoed in the pictures made previously during my relationship.

Your photographs can be described as sort of hybrids between images, sculptures, and installations. What was the conceptual process that drew you towards this aesthetics and visual language?

It was a bit of a shock to realise I had expressed something in my pictures without knowing what exactly I was living at the time. So, blowing them up and having them physically represent the feelings I had during my relationship, made sense to me.

Was it only temporary installations you made at your home, or did you leave them hanging for some time?

I lived with them for quite a while, they were a reminder to not go back.

Since your images do not show any form of destruction but rather focus on escapism and tranquillity, how do you think calmness can become a vehicle to portray something so violent as an abusive relationship?

I had trouble understanding that what I had lived through was domestic abuse because I didn’t relate to the images that I had seen previously of victims of domestic violence. No broken bones, no blood, no bruises. In these pictures I see a quiet tension, things being bent and broken but subtly, just like emotional abuse.

“There’s an interesting link between the process of understanding the work and understanding the mechanisms of abuse. It takes time…”

Recently, you won the Near. Prize for this project, congratulations! This award has most probably led to increased exposure to your work. How do people respond to it?

Thank you! I get mixed reactions, to be honest. Some relate and talk about what they’ve been through. Others reject it because they don’t understand what they’re looking at when they first encounter my images. There’s an interesting link between the process of understanding the work and understanding the mechanisms of abuse. It takes time…

The lockdown and resulting loneliness have led to a sharp increase in domestic violence cases worldwide… What then is your goal with this body of work, and would you say that this project, in the end, became therapeutic for you?

It’s hard to recognise abuse when you’re in it because it’s easily mistaken for love. I hope that this work has allowed, even in the slightest way, for the collective narrative to begin to change. It personally gives me a form of resilience and I’m looking forward to the next project that I hope to share with you soon.

“It’s hard to recognise abuse when you’re in it because it’s easily mistaken for love.”