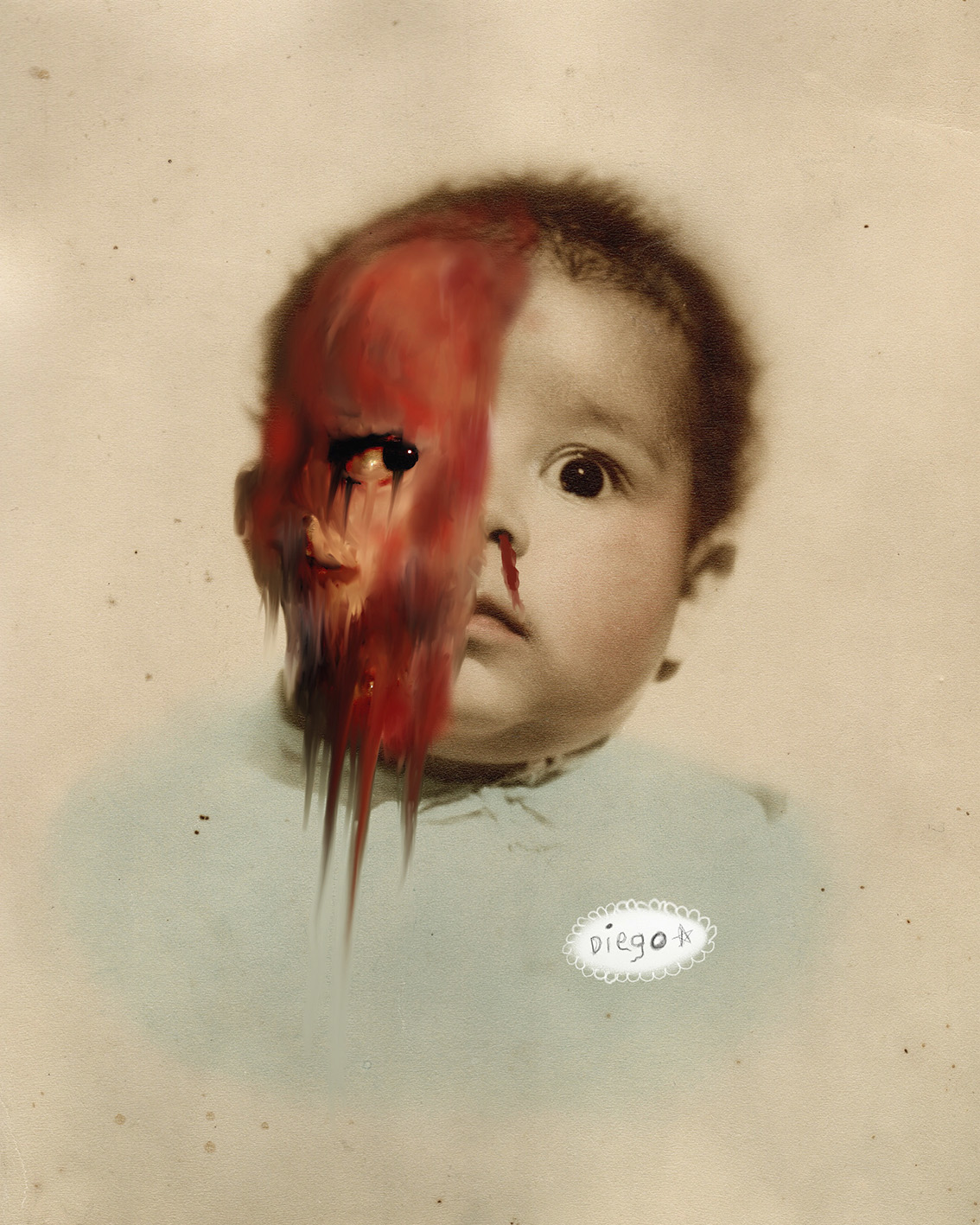

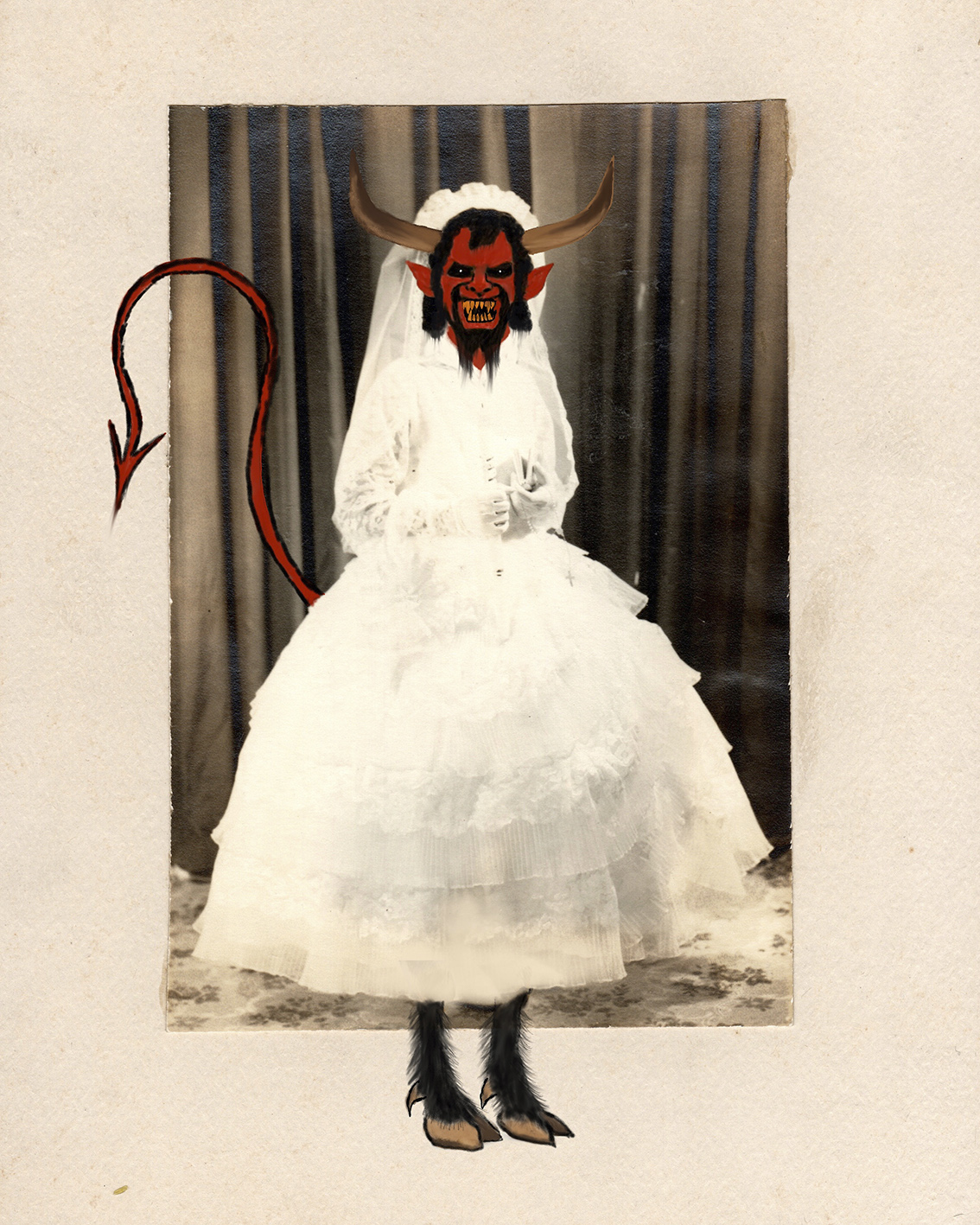

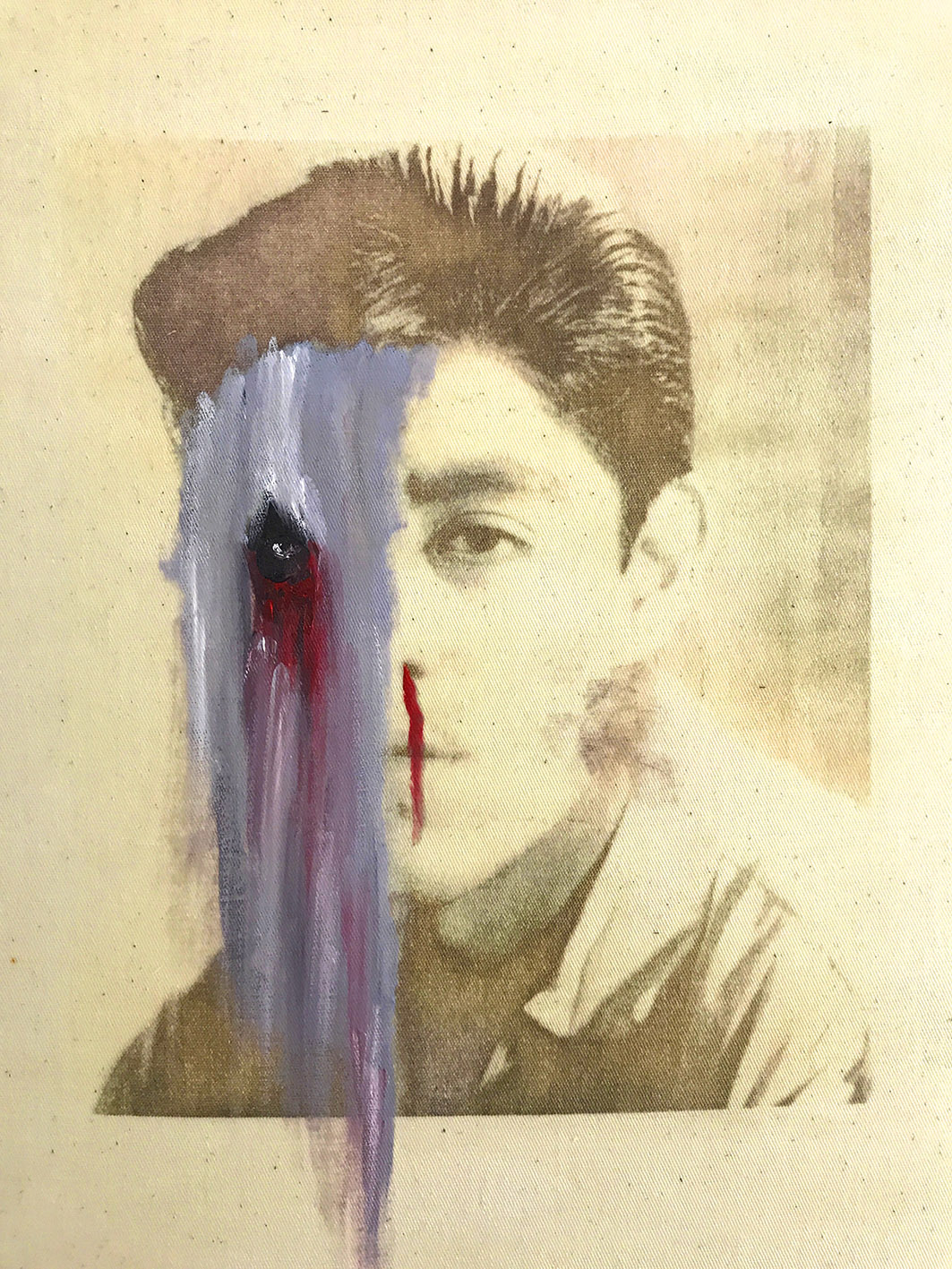

Diego Moreno’s (b. 1992, Mexico) imagery dives deep into his psyche to reflect on the heavy presence of the Catholic church in Mexico and his subsequent struggle of expressing his sexuality. In the project ‘Malign Influences’, he graphically intervenes his family archive through the use of coloured pencils, graphite, Chinese ink, markers or materials such as chlorine or even vinegar to mirror his fascination with terror and monsters.

‘Malign Influences’ was created during the confinement period. How did the idea of applying a family archive come about?

I’ve been working on graphic interventions since 2017, with another photographic project about witchcraft in my family. In this project, called ‘SPECTRUM’, I started to transform the photographic archive and erase the men in my family inspired by botanical illustrations.

My beginnings were a little slow because I was afraid of ruining the photographs. Only from 2018 onwards, I decided to intervene with more precision. Losing respect for the aura surrounding the photographic archive has been a great triumph for me.

The family system is very badly structured. I intervene in the family album because the album is a lie, only ‘the happy moments’ are there, the ones in which we pose and smile even though we are broken inside. At the same time, those celebrated moments are the ones that give us identity in front of the world.

I have conflicted with the male members of my family already since childhood and I have always been associated with the demonic due to my rebellious character. I was strongly maltreated by my family and at school and the image of the monster or the freak was the only image I had empathy with because of the constant rejection. I became a lonely person who took refuge in my imagination to survive.

During my childhood, I also served the church for twelve years, I was an altar boy. The Catholic church was also indirectly abusive towards me because of my sexual orientation – it is a sin to be non-heterosexual in Mexico. So, I grew up with this ideology of the church, the sin and the subsequent suffering.

Where does your inspiration for all these uncanny characters come from?

The characters that I draw on the photographs are beings that live inside my head, and surely if they would live among us, our life would be more fun.

Mexico is extraordinary in the sense that it has a strong connection with the death and the way it personifies evil. But my biggest inspiration for my characters comes from my own fantasies. The imaginary beings I co-exist with, I am not afraid of them. On the contrary, I want to understand their indifference because they were rejected just like me.

I give life to rejection, to what is different, to what many are afraid of. I am fascinated with our own fears and how the collective imagination decides what is beautiful and what is grotesque, I enjoy playing with the viewer’s unconscious.

“(…) I give life to rejection, to what is different, to what many are afraid of.”

The project is based on an apocalyptic vision of the Catholic Church, your highly religious upbringing and the subsequent suppression of your sexual identity. Would you say that your artistic practice is an attempt of subversion and resistance to religious doctrines?

I think religion is a system of silent violence. And art is a way to show our stance on life.

Serving the church hurt me a lot. I was brought up feeling guilty for who I was, I even came to think that I deserved to be rejected, that God was punishing me. You see, religion divides countries, creates wars, destroys human beings. The church condemns the LGBTQI+ community and since its history, it has also condemned women.

For me, this project is funny revenge, it’s my way of seeing the world, of using humour to denounce a system that has damaged humanity. I believe that rebellion is a powerful weapon to generate empathy.

“(…) I believe that rebellion is a powerful weapon to generate empathy.”

Has your family seen your alternative ‘album’?

I have had both good and negative comments from my family. Especially my mother and some of my aunts have been very supportive, and they have even donated me more images to meddle with. On the other hand, my grandmother is not so keen on the idea of me intervening in the family memory. She always says that many of the people in the photos are very special to her, that many are already dead, and we must respect them. As she is ultra-catholic, it is difficult for her to understand my way of seeing the world in this project, but her unconditional love for me always overcomes that rigid religious position of hers and sometimes she even makes jokes with me about it.

Do you feel that these creative interventions or appropriations have helped you accepting your identity?

Totally! Now I find myself living another story, I can inhabit a present without being disturbed or lonely. Photography has helped me to create a posture towards life, to rebuild my family and to know that I want to be happy. It sounds very cliche, I know, but I think that thanks to deepening these photographic projects I have been able to empathize with the human complexity, pain and differences.