Linda Zhengová

Monsoons Never Cross the Mountains

Softcover, 167 x 237 mm, 84 pages

€25

In the past five years, Camillo Pasquarelli (b.1988, Italy) has been intensively working in the valley of Kashmir, a disputed region between India and Pakistan since 1947 and currently one of the most militarized zones on the planet. ‘Monsoons Never Cross the Mountains’ is now published as a photobook that, alongside showcasing the portrayal of local citizens and their surroundings, serves as an introspection of the artist.

What exactly was it that made you want to explore and document the area of Kashmir?

It was 2011 when I visited Kashmir by chance – during my first trip to India with my girlfriend. Struck by both the poetic beauty of the land and the tragic dimension of the regional conflict, I realized how the journalistic representation of the international dispute too often dimmed the inhabitants of the valley with their political aspirations and sufferings.

I was attracted by the strong cultural, religious and geographic differences of Kashmir. The title of the book comes from a verse by the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali that describes the distinctive local climate which — due to its surrounding mountains — is quite a world on its own compared to the binary rainy and dry seasons of the rest of India. I would say it is a powerful metaphor of the “natural” repulsion to the Indian nation.

In 2015, I spent six months in Kashmir to work on my master’s thesis which explored the separatist movement and the daily life of locals and their political struggle from an anthropological point of view. At first, photography was only a tool to collect visual data, a kind of notebook for my research. But soon, the process urged me to develop this further and after the fieldwork and months spent in the valley, I was just emotionally attached and couldn’t resist coming back.

How did you approach the people you photographed? Did you have a fixer on your journey?

The photographs of people were created during very different situations. Some portraits were the result of causal encounters while others are good friends of mine that I’ve known for years.

In general, I try to avoid having a fixer. I feel a bit uncomfortable in that kind of relationship – asymmetric in a sense – and I also really enjoy walking around the places I am working at, giving space to a bit of serendipity during my process. If you can really immerse yourself in a place by simply being present, you don’t really need a fixer.

Moreover, hanging around with local journalists or fixers might get you in trouble with the security forces who will notice very easily that you are a foreign journalist and start tailing you (at the beginning), arrest you or kick you out of the country in the worst-case scenario.

“If you can really immerse yourself in a place by simply being present, you don’t really need a fixer.”

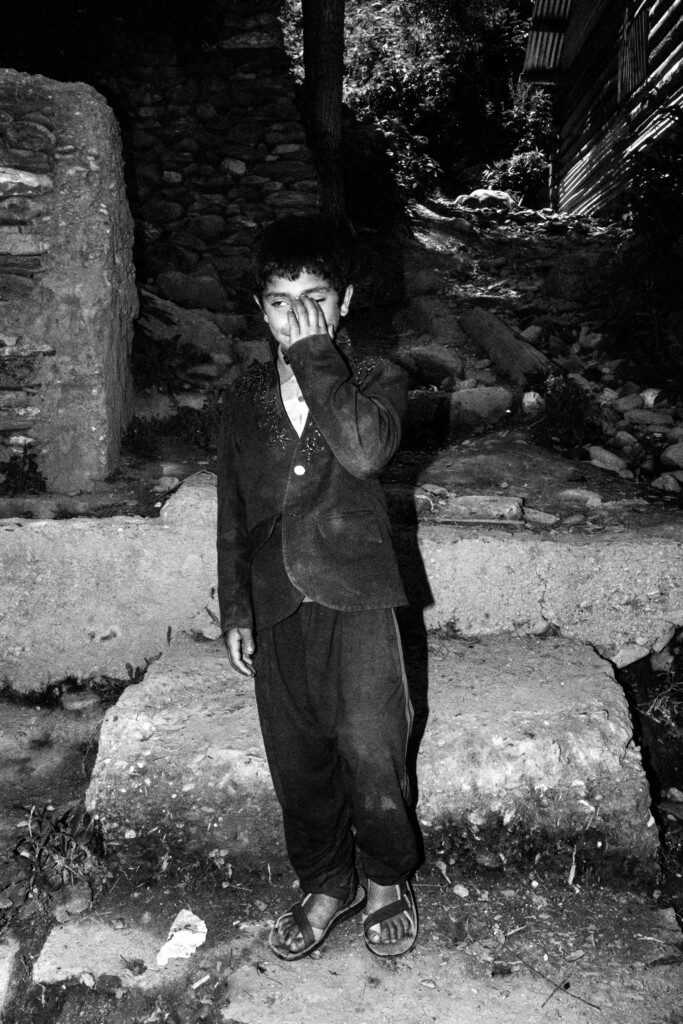

Many of your photographs are portraits of children. Why did you decide to focus on the youngest generation?

After some point on my trips to Kashmir, I started to feel very uncomfortable with the body of work I had in my hands. In 2016, I attended an MA in Photojournalism and this was the first visual vocabulary that I applied to approach the issue. However, after some time many questions troubled me:

How do I depict a conflict zone? How do I photograph violence and suffering from the perspective of a privileged white European man? How do I deal with the “violence” of my gaze? And ultimately, what is the relationship between the image and the spectator when I depict violence?

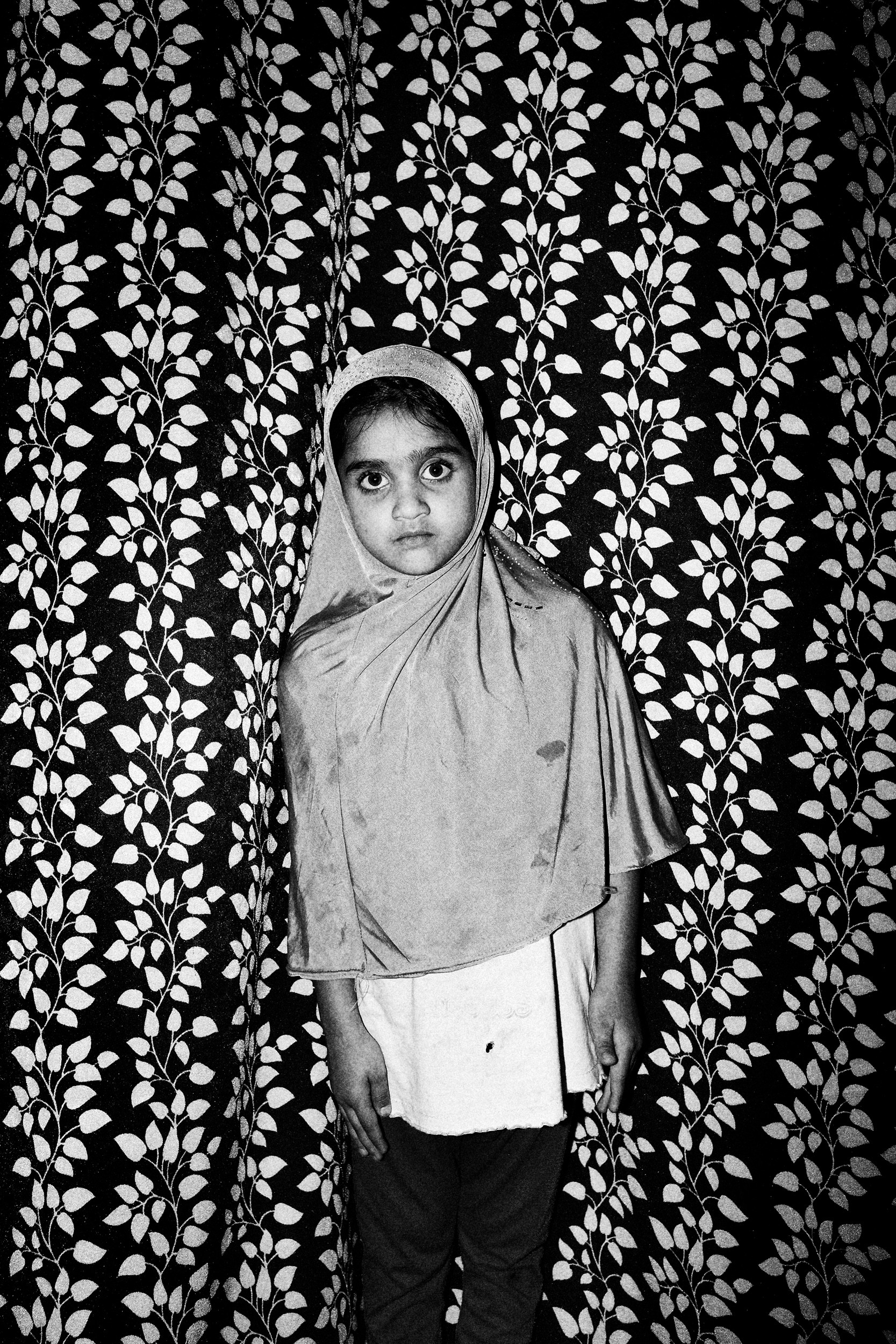

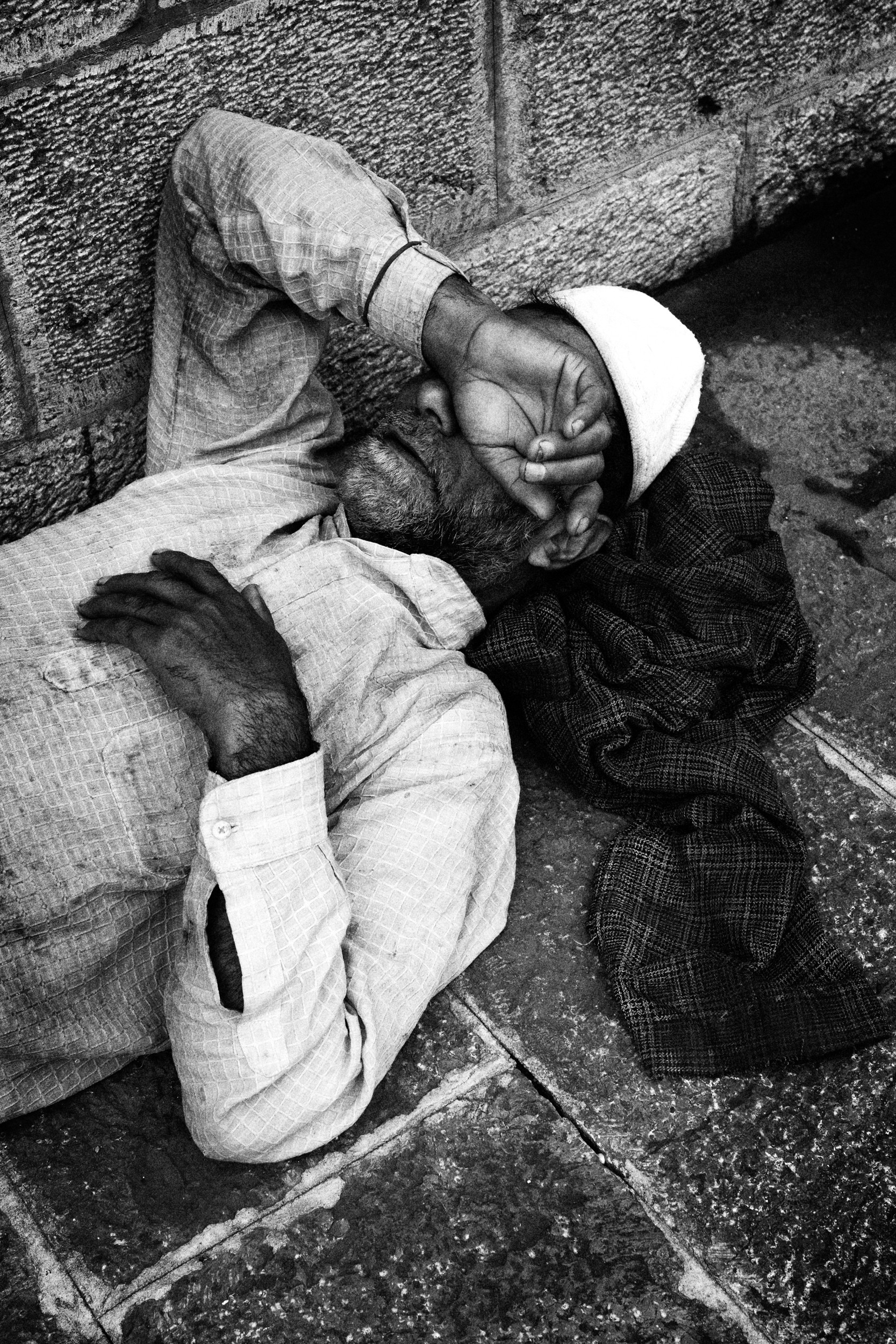

So, I went back and decided to completely change my way of working. I tried to photograph in the most open way that I could – to remove all the documentary structure from my vision, abandoning the need for informative image and following a more innocent and naive practice of reacting emotionally and through the senses of my body to what was happening in front of my eyes.

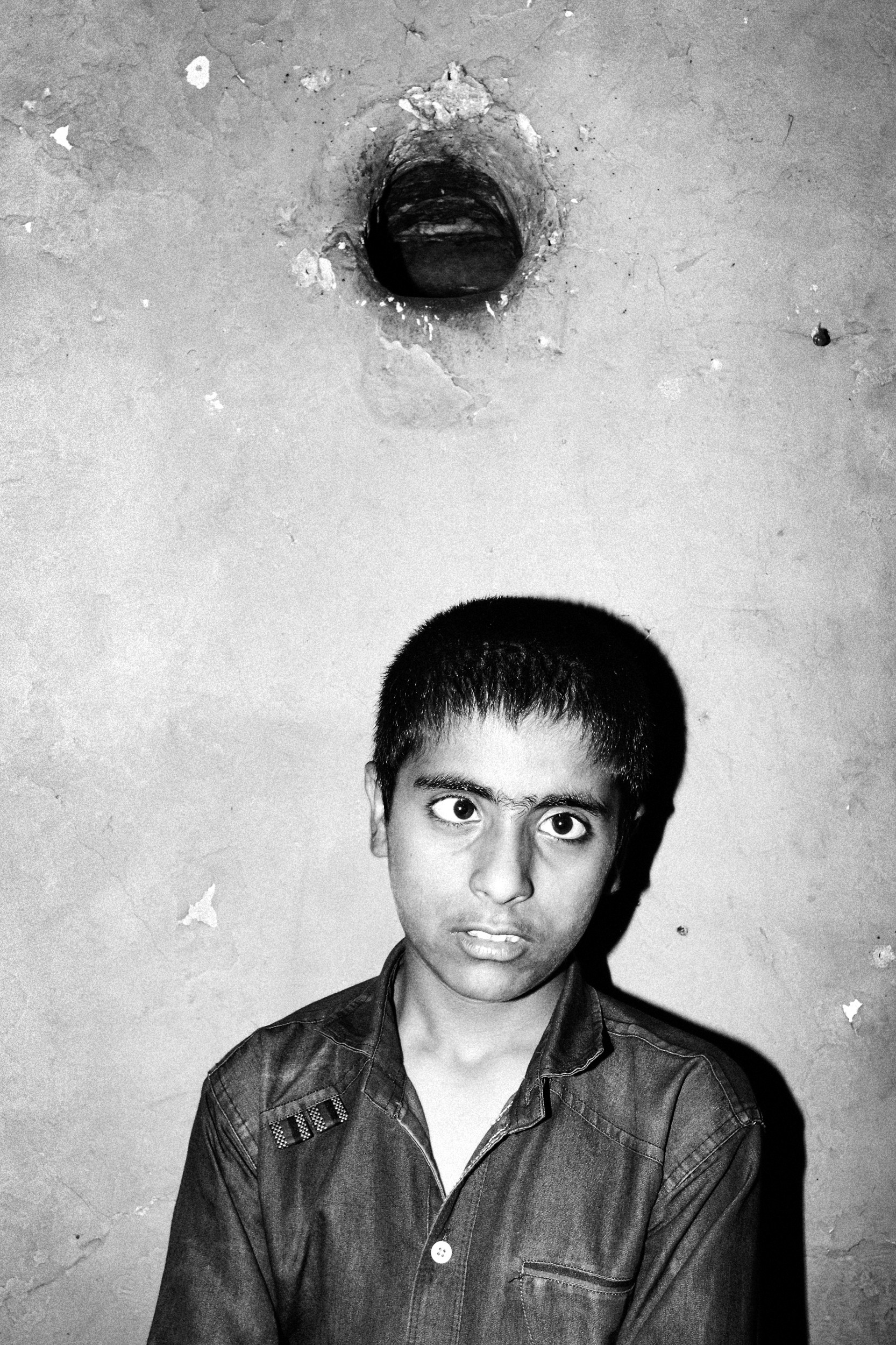

It was never my intention to realize a self-referential project, like: “this is my point of view on Kashmir.” I felt that I needed a more specific and honest point of view, and that is when the idea of the children’s gaze came up. Through their eyes, I was able to create an emotional landscape where things are not observed in a rational way – exactly as children perceive reality – reflecting a sense of disorientation and triggering an eerie experience. Their restless gaze allowed me to transmit a claustrophobic atmosphere that pervades all the images; reaching a point where what you see is completely decontextualized and until you reach the last image of the book, you never see what Kashmir actually looks like.

“Their restless gaze allowed me to transmit a claustrophobic atmosphere (…)”

In your book, you combine colour and black and white imagery. Do different types of imagery have distinct roles in the book?

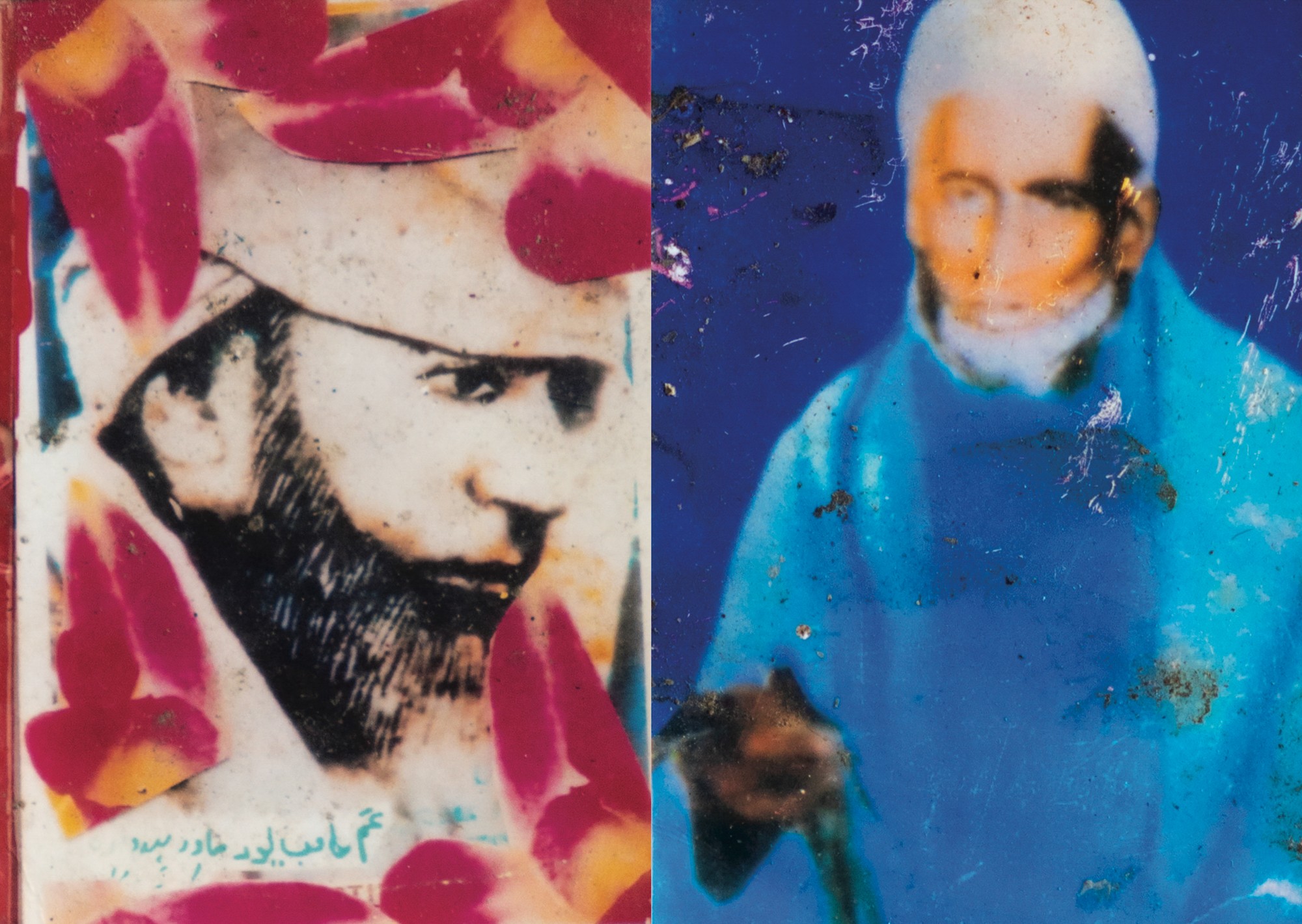

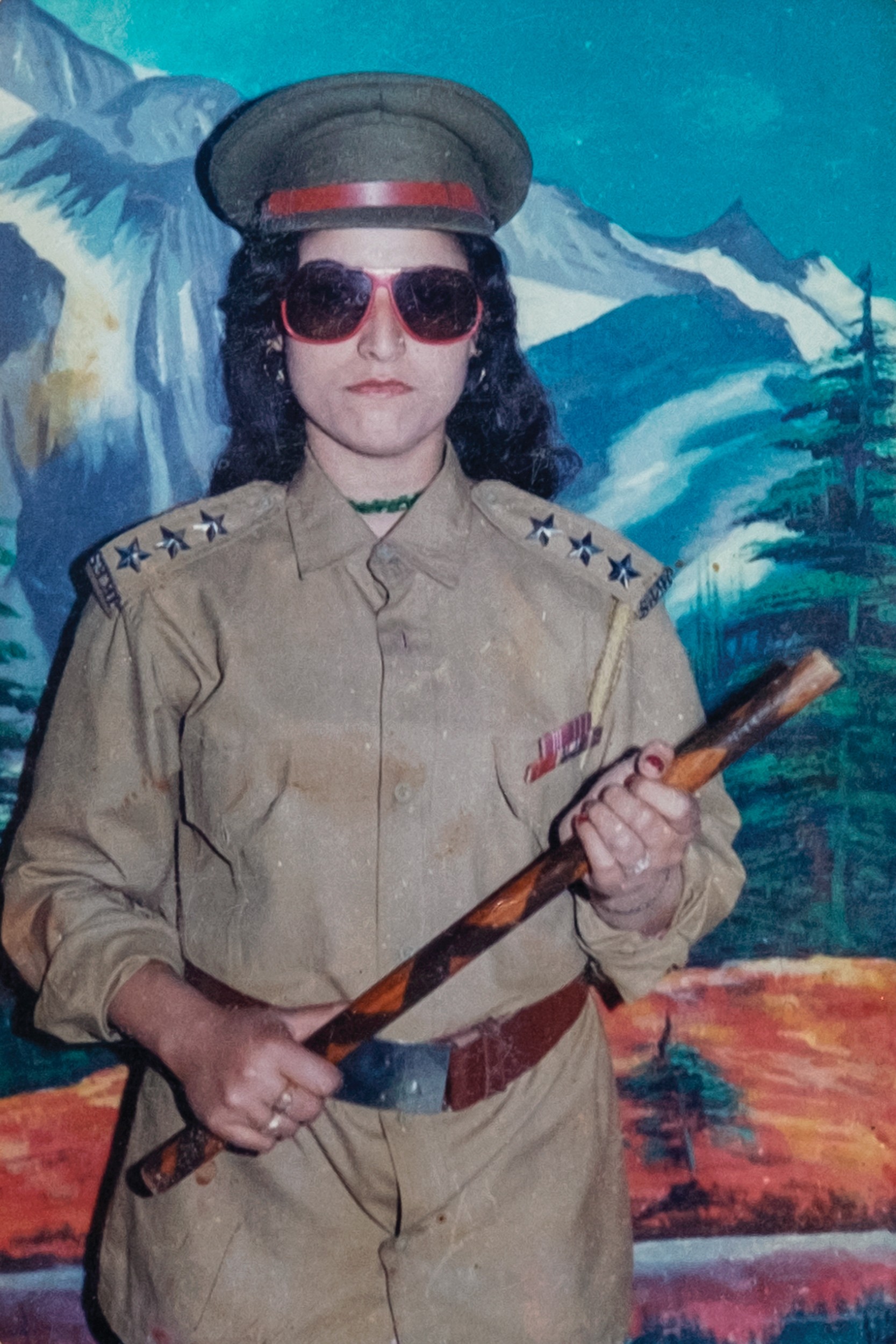

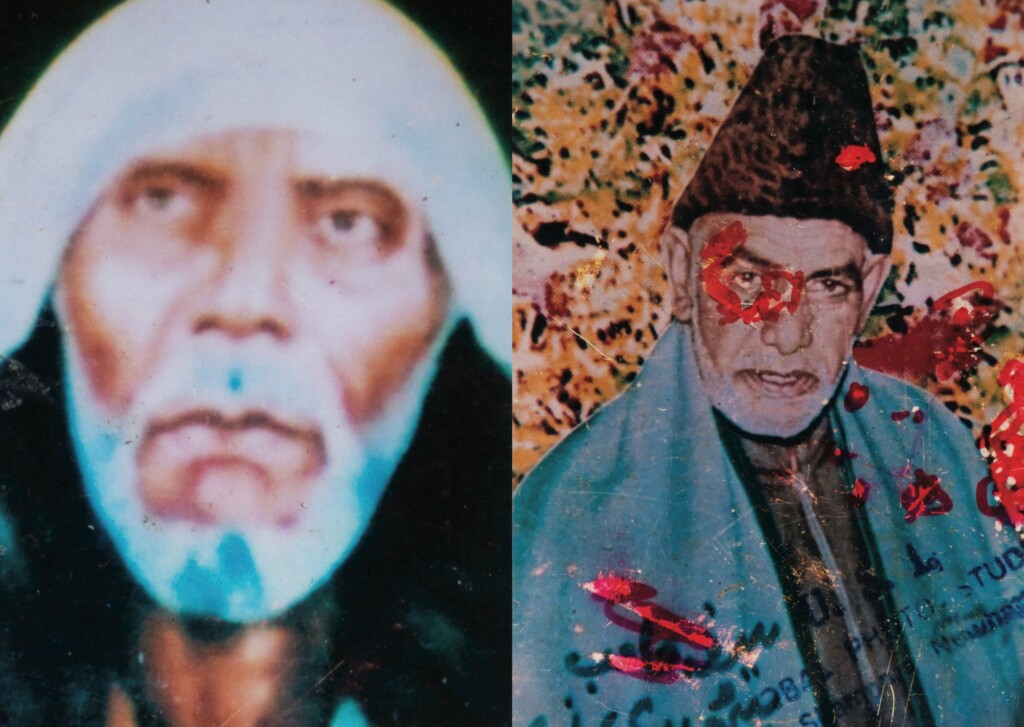

The black and white photos are intertwined with cards depicting deceased Pirs (Sufi saints), which are sold at shrines by street vendors.

Kashmir is primarily a Muslim region and Sufism is a mystical Islamic belief and practice that is very widespread there. Nowadays, the veneration of the martyrs who sacrificed their lives for the pursuit of Azadi (“freedom” in Urdu) seems to be following up on the popular cult of commemorating Pirs, suggesting that honouring the dead is inherent to Kashmiri culture.

During my travels, I collected many of these “holy cards”. Besides finding them visually appealing, they also remind me of the Padre Pio cards — a popular Catholic saint — that everybody in Italy used to have in their wallet and hanged on the wall at home. Additionally, the texture of the Sufi cards is fascinating as they are stretched, damaged and they look like a child scribbled all over them.

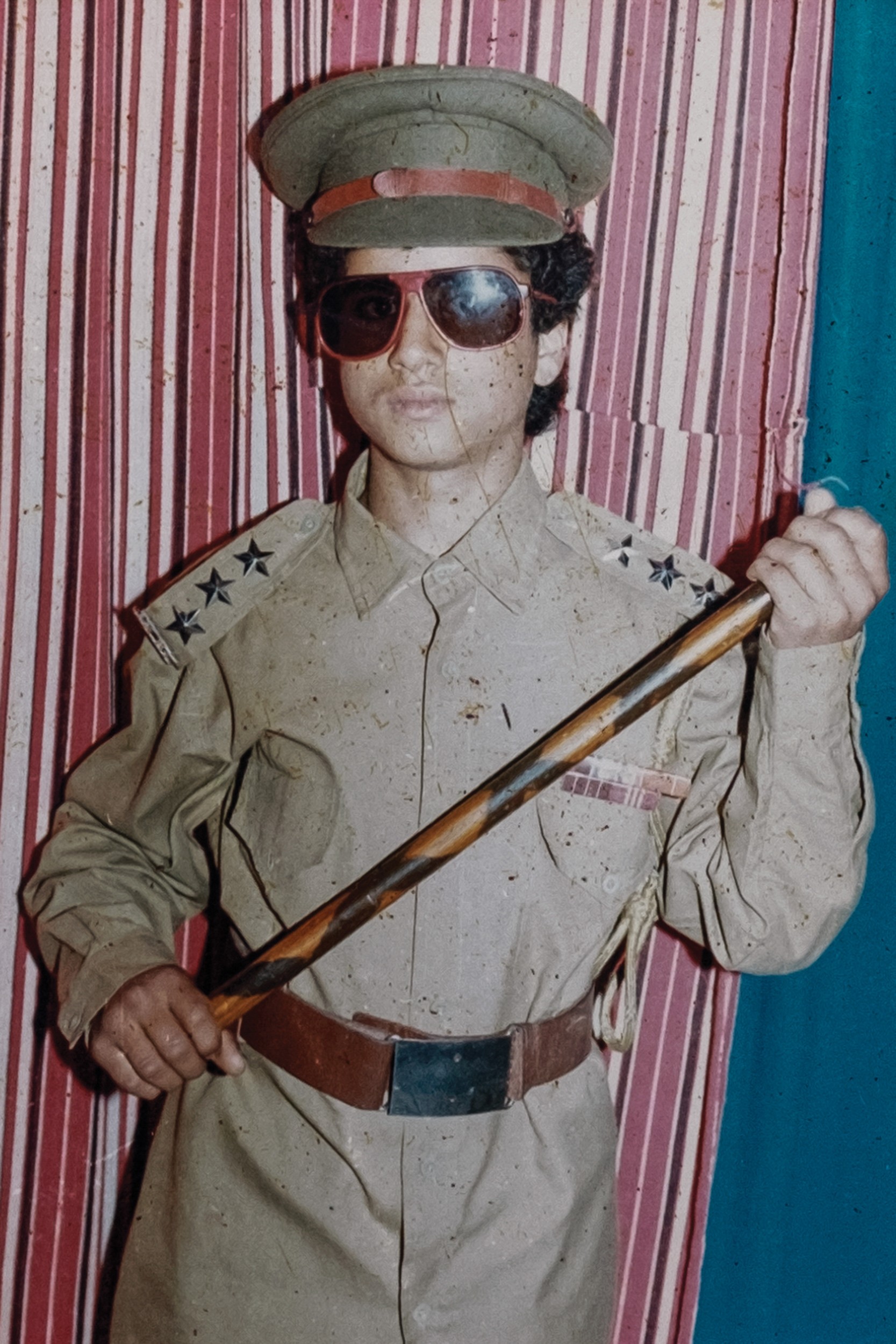

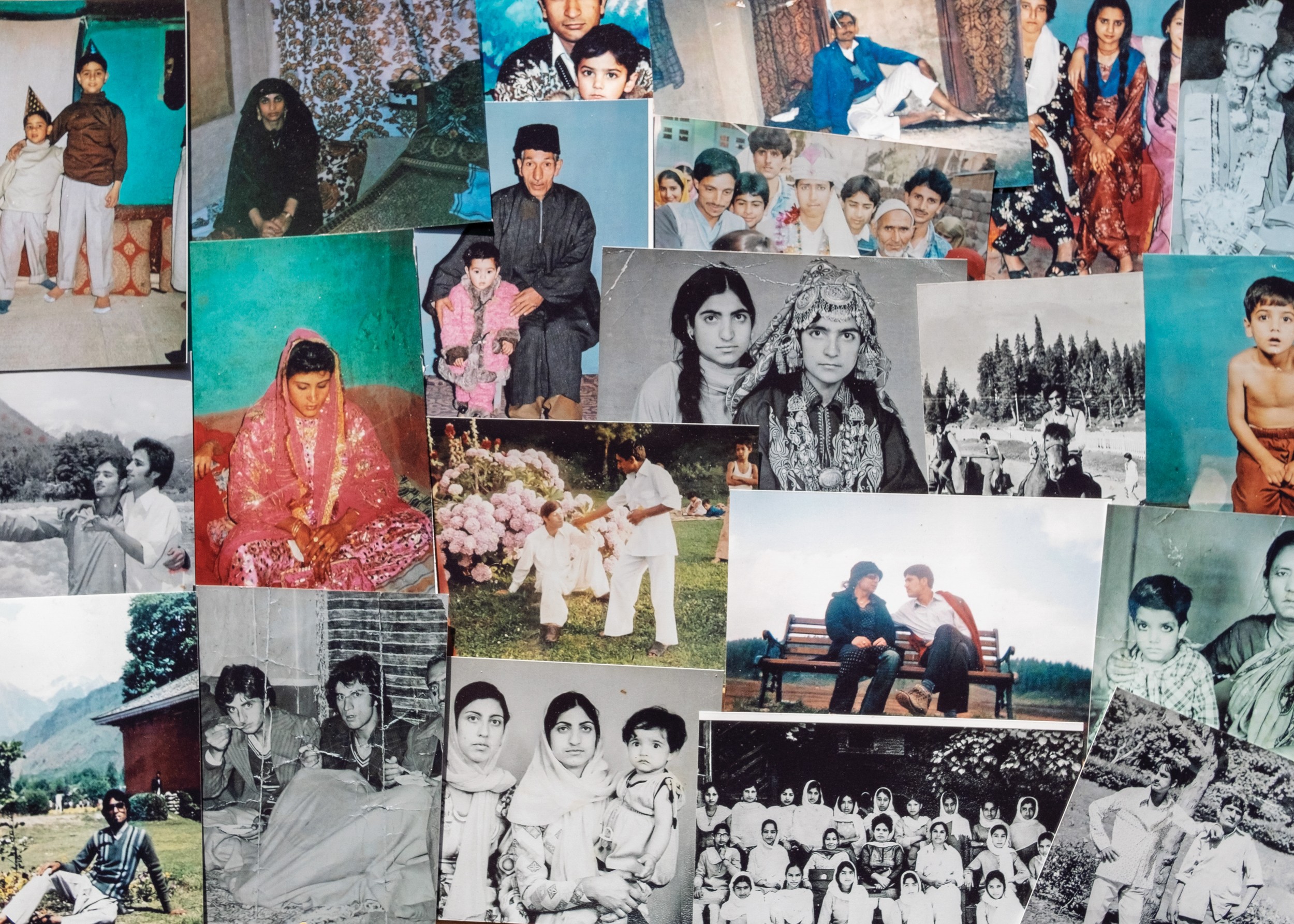

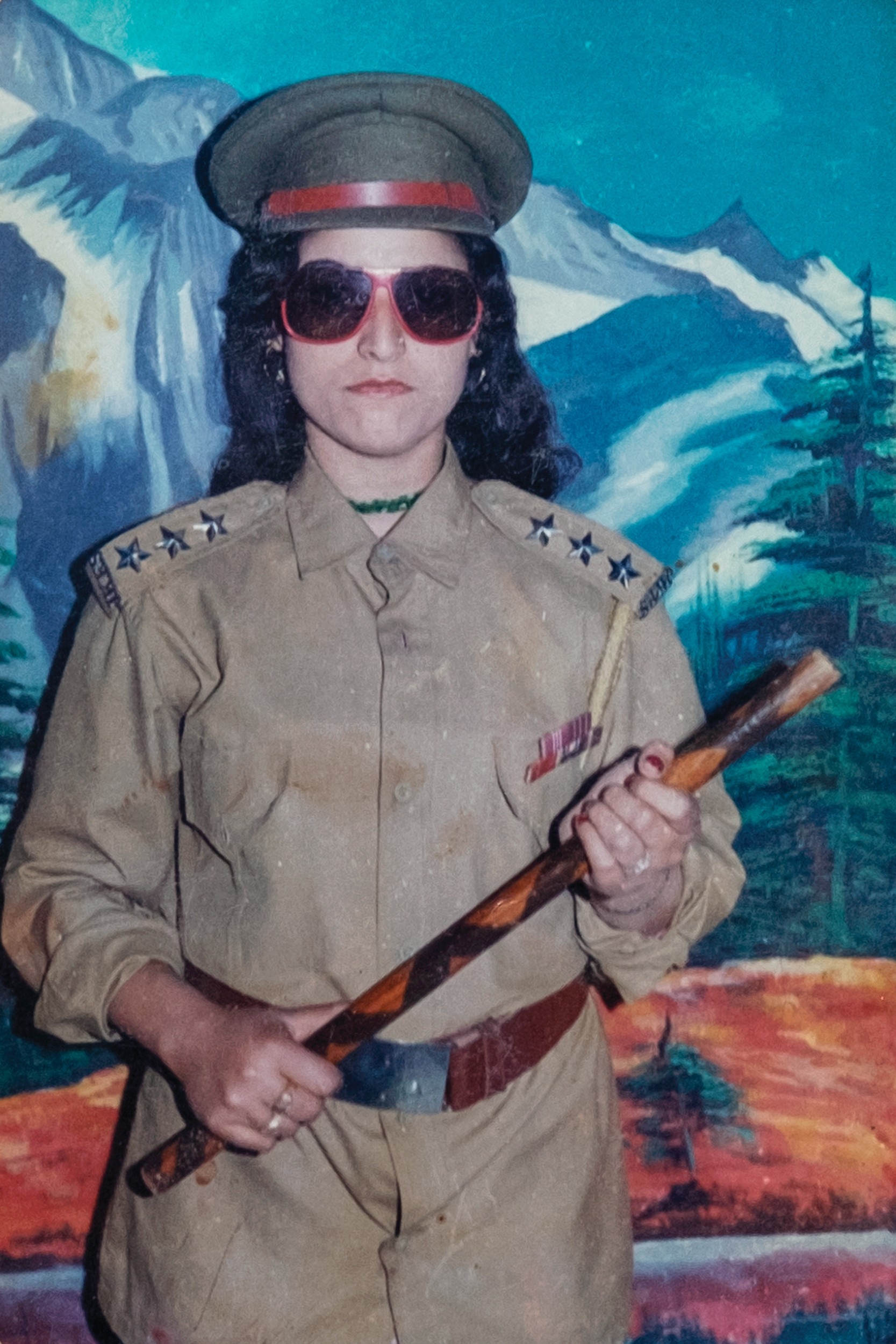

At the end of the book, there is a collage composed of family photos of my friends who were born in the early ‘90s — the decade when violence broke out between Kashmiri armed groups and security forces. In the memory of those who lived through those times, I expose the traces of a violent past that were never resolved, those that remain unredeemed.

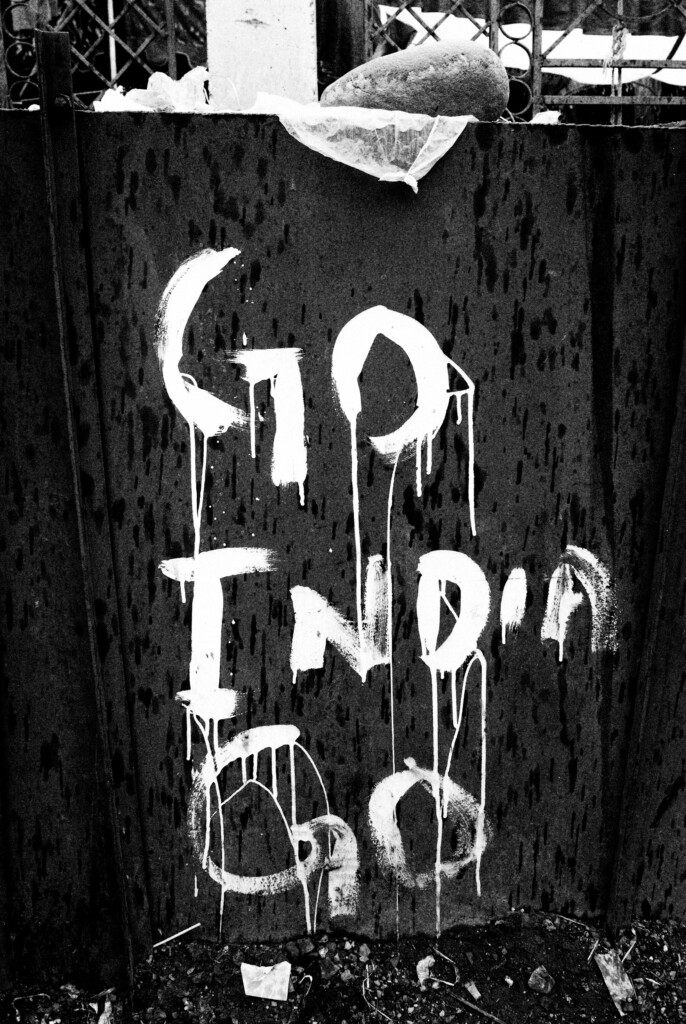

Taking in mind the political nature of your project, do you consider this book to be a form of protest?

It aims to contribute awareness about the situation in the Kashmir valley, and the violations of human rights happening daily — something many people in Europe or Western countries are still unaware of.

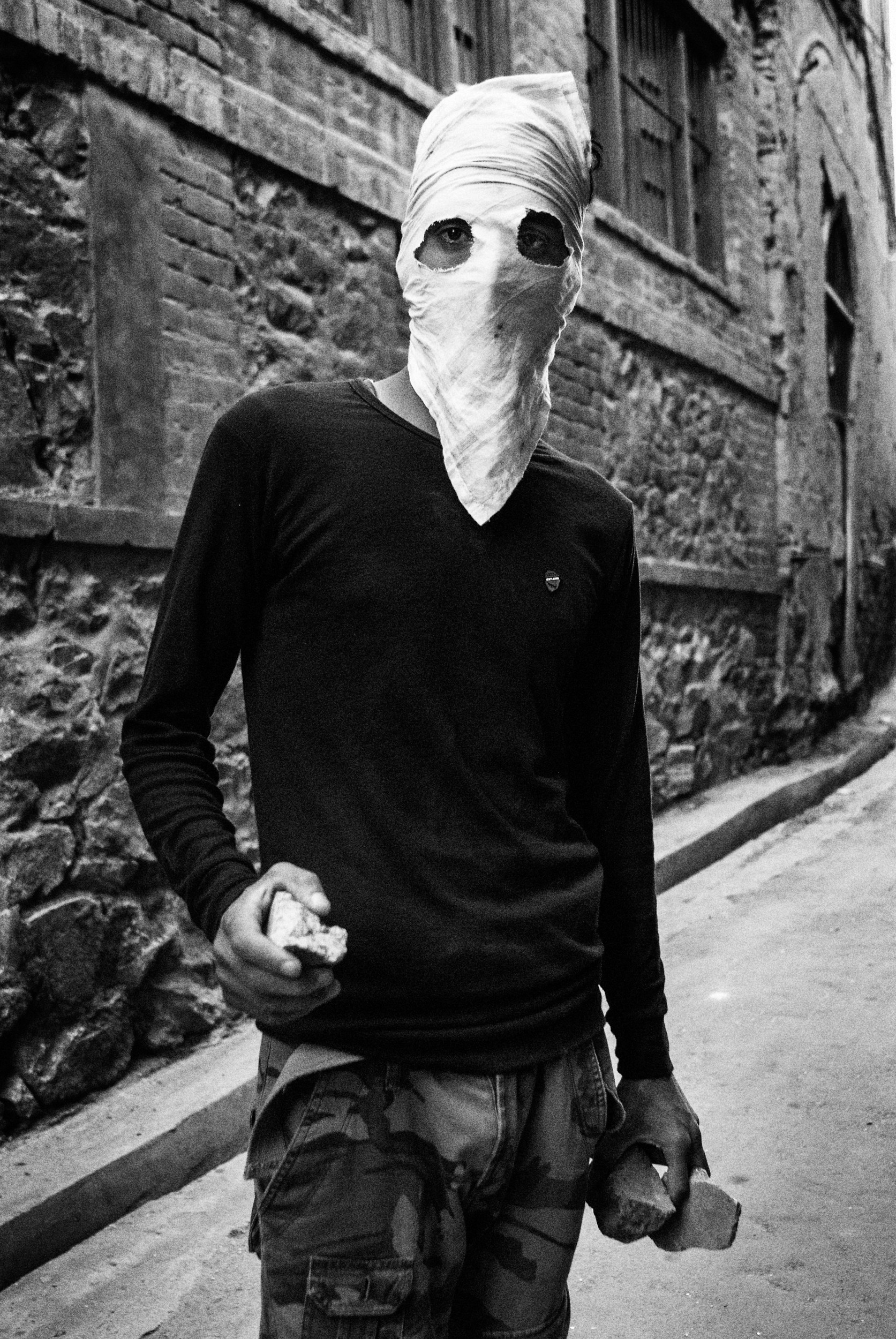

I believe that all my doubts concerning the political role of representation pushed me to propose an alternative approach to the classical depictions of war zones. For example, if you just google-search “Kashmir” you will be overwhelmed by images of soldiers, barbed wire and urban clashes. I tried to overcome these visual stereotypes. For instance, by completely avoiding showing Indian soldiers. The only reference to them is a scratched graffiti on the wall with drowned soldiers.

In the end, this body of work is meant to be seen as a critical stance towards traditional documentary photography, questioning the assumption of the genre’s untouchable bond with reality and truth while embracing subjectivity and authorial self-revelation.

Monsoons Never Cross the Mountains is available for purchase here.