What is the status of the photograph in the context of imprisonment? Can a dossier of collected files and documents help us arrive at the essence of incarceration when questions of visibility, ethics and aesthetics intersect? Two recent publications touch on this dilemma in seemingly opposite ways. One is related to the bureaucracy of an institutional complex that surrounds the concept of custody; the other is more concerned with the emotional aspects of being put in isolation. Both, however, unshackle their content from a confined perception.

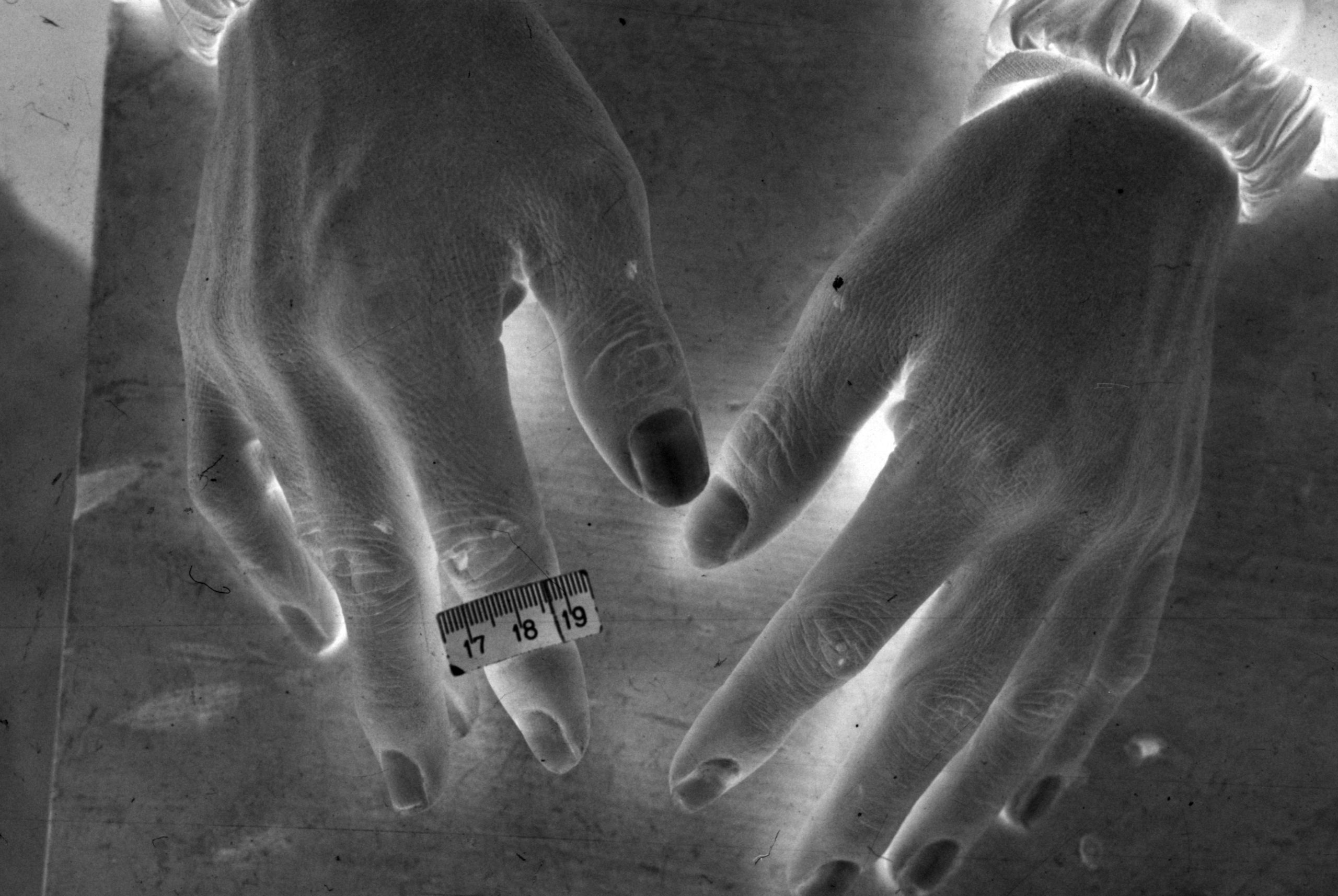

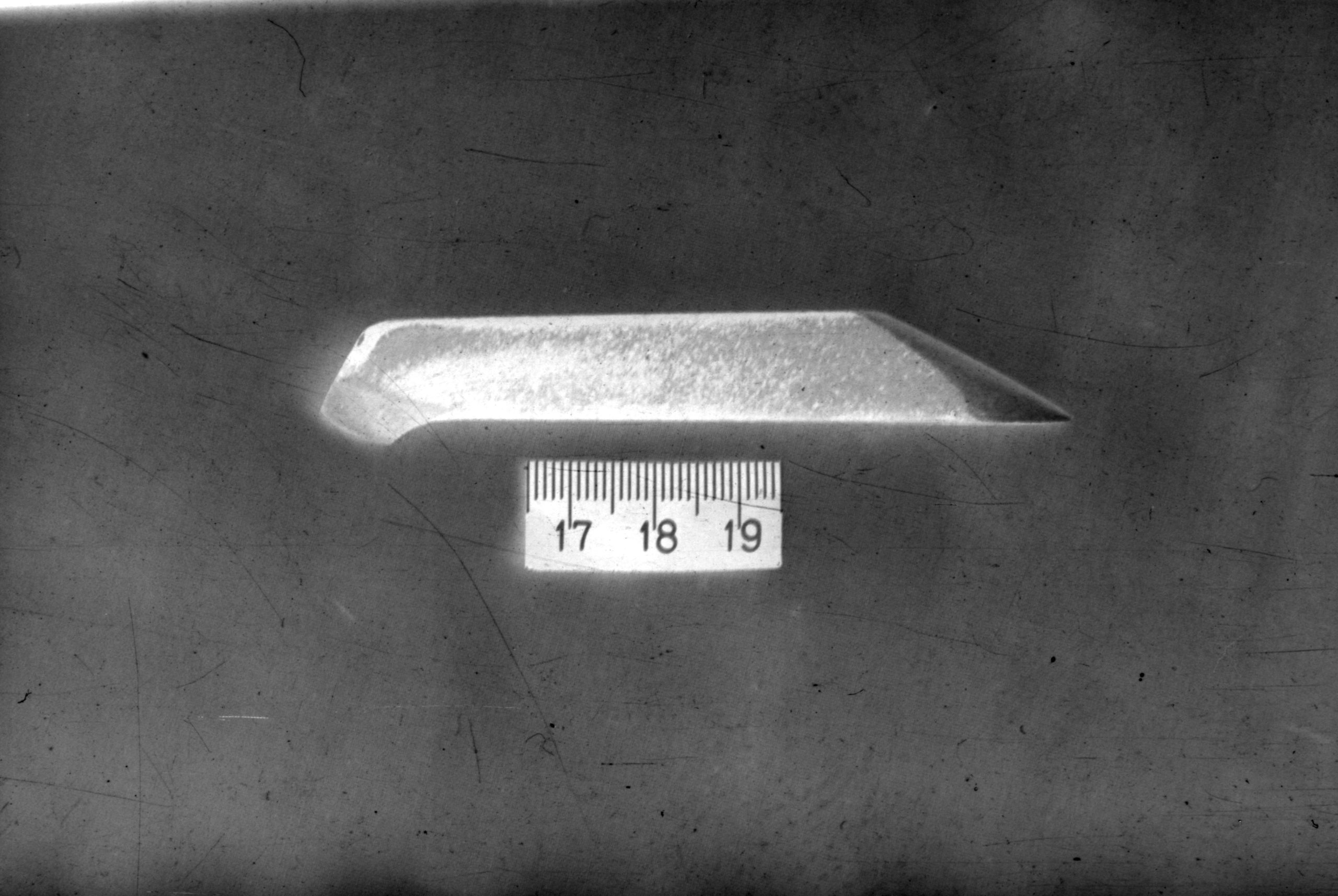

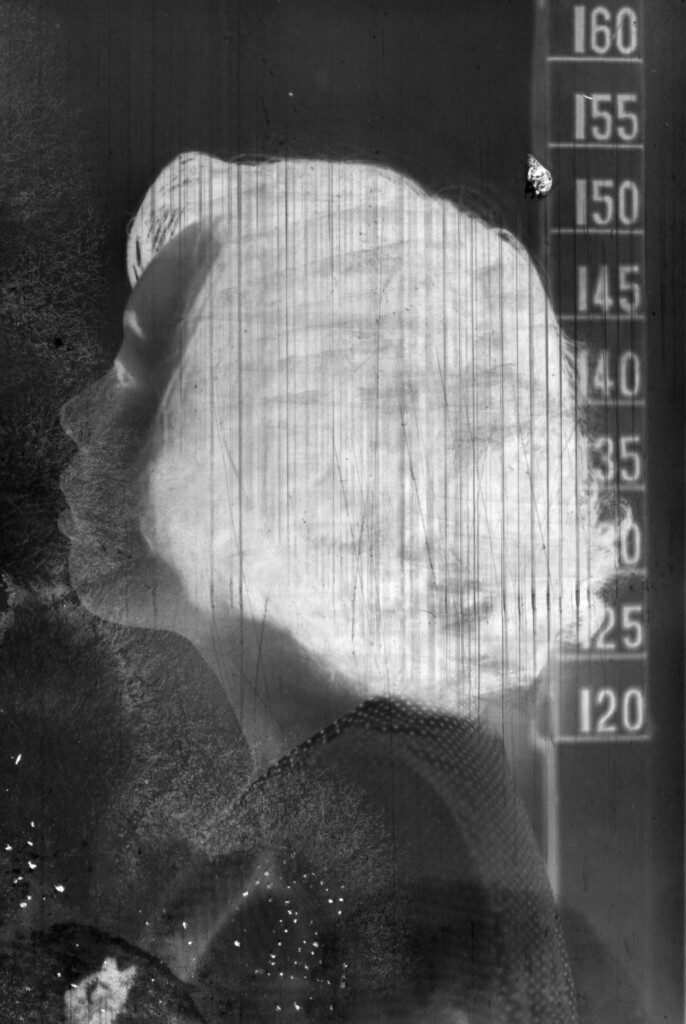

In 2009, Thomas Sauvin (b. 1983, France) salvaged discarded negatives from a recycling plant on the edge of Beijing in order to repurpose them as visual art objects. The negatives, which he purchased by the kilo from the plant’s owner (their silver nitrate content made them valuable), have been taken out of their original context and successfully transformed into amazingly aesthetic artist books. Sauvin’s ongoing Silvermine Project – which by now encompasses more than 850,000 anonymous photographs spanning the period from 1985 to 2005 – has resulted in several publications, with 17 18 19 (Void, 2019) being the latest. The book is concerned with the practice of Chinese police department photographers, and displays objects seized from convicted inmates.

One of Sauvin’s discoveries was an archive of more than 15,000 scratched black and white negatives, shot at one of Beijing’s detention centres between 1991 and 1993. At the time, scanning rejected official Chinese material could have jeopardised the Silvermine Project, which he’d already started. Sauvin therefore kept the material un-scanned for almost a decade while living in China. Now, many years later, he has decided that a selection of those negatives is ready to be released. They come across as ambiguous visual puzzles with an excess of meaning; a hyper-potency that leads only to more uncertainty rather than bringing us to a point of “knowledge”.

What are the stories behind each item?

The images themselves are factual, and were only ever made with utilitarian intentions. But what are the stories behind each item? Thanks to Sauvin’s appropriation – and that of the designer (the book, printed with silver ink on black paper, is an aesthetic object in itself) – it’s a pleasure to look at these images with intensity, yet, the longer you look at something, the more meanings you’ll find. To paraphrase British art critic John Tagg – a significant voice when it comes to critically reviewing the aspect of “truth” in photography – what we are dealing with here is a “burden of representation”.

But wasn’t that already the case, at the time of the original production of the negatives? Photographs were used as documents, evidence and records of everyday matters in courtrooms, hospitals and police stations, on passports, permits and licences. What sorts of agencies and institutions had the power to give them this status? In the late 1980s, delving into 19th- and early 20th-century collections of photographs assembled by prison administrators, the police, hospitals and city planning bodies in France, the United Kingdom and the United States, Tagg built a thesis on how photography was applied as judicial, social or medical “proof” of something that would benefit a certain power mechanism – most significantly, the State.

Tagg questioned how the meaning and understanding of documents and archives were always constructed (by an authority). Since then, this kind of critical review has become common practice – although it’s often not as academic while being incorporated into a more open discourse.

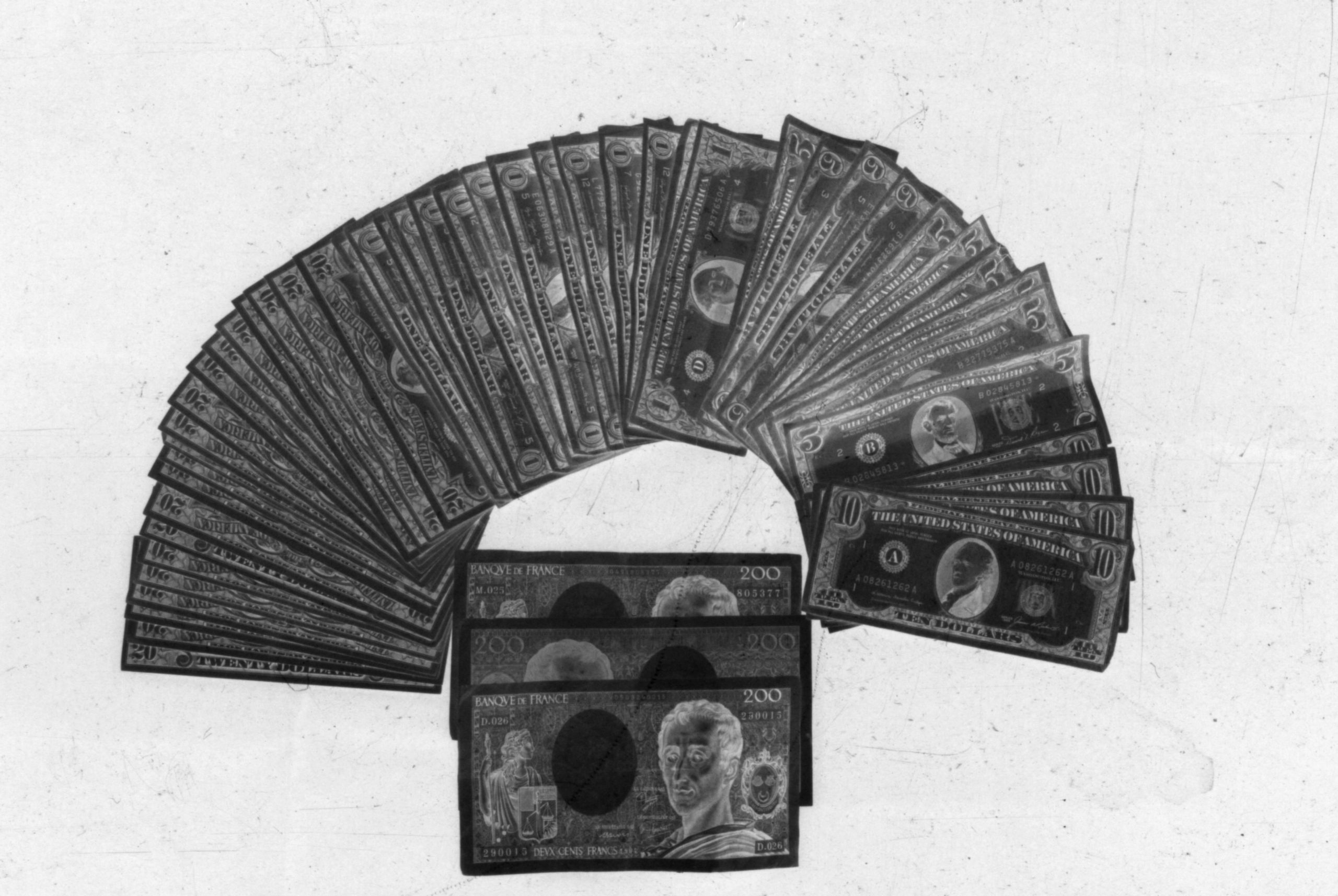

Sauvin’s 17 18 19, for instance, is concerned with a forensic aesthetic, as found in the Chinese judicial system, but he also puts various tropes of evidence under scrutiny without providing any explanation; impassive presentations that trigger speculative conclusions.

The book’s title – 17 18 19 – derives from a ruler (3 cm long, marked from 16.5 cm to 19.5 cm) used in the photographs by the Chinese authorities to provide a scale for some of the seized goods depicted: various knives and other sharp objects, clothing, cash (most often of small denominations, which seems to indicate the “petty” nature of the crimes committed). Assorted consumer goods (cassettes, televisions, cameras) also appear, hinting at the date when the photos were taken. These are excavated cultural artefacts serving an archaeological purpose – to be observed and to be studied with great curiosity.

17 18 19 is enigmatic in how it shows the originally bureaucratic content: the black pages allow the photographs to be printed as negatives and the metallic silver ink ties the content to its genesis, the Silvermine Project. But the hermetic nature of the book also triggers a critical awareness, a notion of recycled submission. The authority of the Chinese penitentiary institution has been replaced by the authorship of the artist, who remains in full control of the “arrest” of our interpretation – by the lack of context.

The negatives in Sauvin’s book thus speak another, more evocative language. Nevertheless, in the words of the French philosopher Roland Barthes (Camera Lucida): “It is precisely in this arrest of interpretation that the Photograph’s certainty resides.”

Can a photograph reference something that it doesn’t depict?

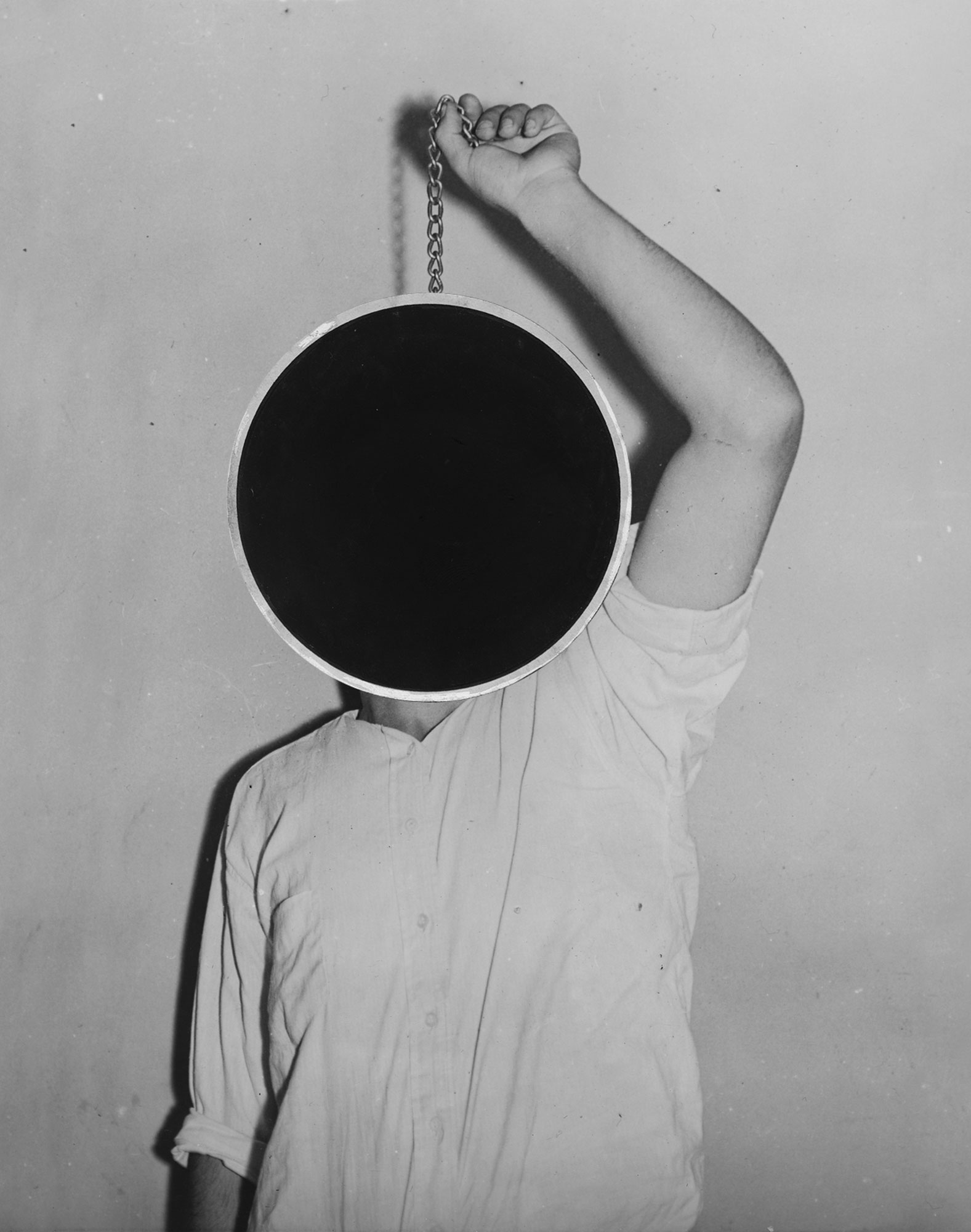

How is it possible to explore what prison does to a prisoner, without photographing inside the prison walls? By giving a voice to inmates and their families and addressing prison as a set of social relations rather than a mere physical space. This is how Edgar Martins (b.1977, Portugal) proposes to rethink and counter the imagery normally associated with detention. A multi-media body of work, What Photography & Incarceration Have In Common With An Empty Vase developed from a commission by Grain Projects (a UK arts organisation) in collaboration with HM Prison Birmingham and its inmates serving long-term sentences. Martins also interviewed the prisoners’ families, as well as a variety of other local organisations and individuals.

Composed of three distinct sections, and making use of film, audio, sculpture and installation, the work shifts between image and information, between fiction and evidence: “strategically deploying,” according to Martins, “visual and textual details in tandem so that the viewer becomes aware of what exists outside the confines of the frame.”

Believing that photography often sensationalises prisons and the lives of inmates, Martins vowed to tackle the subject differently. From a humanist perspective, the work seeks to reflect on how one deals with the absence of a friend or family member, an absence brought on by enforced separation. But it also touches on philosophical questions such as: how does photography represent a subject that is hidden from view? Can a photograph reference something that it doesn’t depict?

People have always aimed to overcome (or at least to reduce) the power of photography to replace living, emotive memories with static and historical images, and they were mainly drawn to the physical presence of the photograph itself. By contrast, the two-volume book What Photography & Incarceration Have In Common With An Empty Vase addresses prisoners’ fear of being forgotten, and it does so effectively by not showing them – thus further enquiring into notions of visibility and invisibility.

Martins uses visual representations of violence and absence to allude to the condition of the prisoners, their feelings of emptiness and their relationships with their families. He also made friends with a few of the inmates, and explores photography’s ability (supported by diary notes from the prisoners and appropriated newspaper imagery) to evoke a kind of nostalgic sadness, a warm feeling towards anonymous yardbirds. At the same time, he probes the medium’s ability to contain what exists outside the confines of the frame. Who – which actual people – are the subjects of the images subjected remains an enigma, but what is made evident is the significance of their non-appearance.

_

Since its inception, photography has established new forms of creative expression, but it is only very recently that artists are concerned with reactivating socio-political processes that for long were deemed as “fixed”. Together, these constructs propose a new agenda for theorising photography as a heterogeneous medium that is becoming an ever more dynamic and complex discipline. In return, the viewer becomes more actively engaged, in order to arrive at a better understanding of these transformations, paradoxes and ambivalences within contemporary photographic practice.

Photography and memory do not mix.

The critical reflection is not a new phenomenon in itself. Some of photography’s most insightful critics, including Roland Barthes, have already argued, decades ago, that photography and memory do not mix, that one even precludes the other. Barthes even claimed that “the Photograph is actually blocking memory, quickly becoming a counter-memory” – that is, the image replaces the memory – but he was nevertheless impressed by the ways in which the medium could still ignite feelings and release sensations.

The phrase “arrest of interpretation”, as suggested by Roland Barthes, marks the evidentiary power of the photograph. It can be understood as captivating the attention of the viewer, but also in the sense of “arresting” – stopping – further questions. However, the onlooker is not stripped of his critical view. We still witness certain structures that have shaped the meaning of Sauvin’s negatives, evidence that cannot be erased; they carry the silhouettes of the Chinese prison system, and the traces of a consumer culture as shaped in Beijing in the early 1990s.

Likewise, Edgar Martins successfully addresses the essence of institutionalised imprisonment, be it that he explores photography’s ability to “unlock” its potential with a more empathic approach – by means of abstraction. It can be expected, considering the contemporary experience of state-ordered “lockdowns”, that other visual artists will soon follow with not only laying bare the phenomenon of systemic “quarantine” but also, significantly, the burden of its visual representation.