GUP Magazine is media-partnering with Belfast Photo Festival this year. For the occasion, to underline our mutual interest in addressing global issues by way of photography and to make these works available to a wider audience, we have been given the opportunity to select and highlight a few submissions to the Open Call of the Belfast Photo Festival (now closed) from an already incredible longlist. We will feature these selected artists throughout the months of June and July.

Documentary photographer Louie Palu (b.1968, Canada) feels right at home in the perennial cold of the Arctic region. In a place where daily temperatures average minus 50 degrees Celsius, and one can go for days, if not weeks in near darkness, nature reveals its true, omnipotent power — and yet, the Arctic is warming up to three times faster than anywhere else on the planet, and in two decades may be faced with the first ice-free summer in history.

Palu has made over 24 trips to the Arctic since the early 1990’s, resulting in over 150,000 photographs, documenting the transformations taking place in this vast and isolated region. The unprecedented consequences engendered by our drastically changing climate have opened up a multitude of complex geopolitical and ecological issues: while the world’s most powerful nations scramble to gain a foothold in the North in an effort to secure access to natural resources, scientists are scrambling to understand what the rapidly melting sea ice and thawing permafrost will mean for the future of our planet.

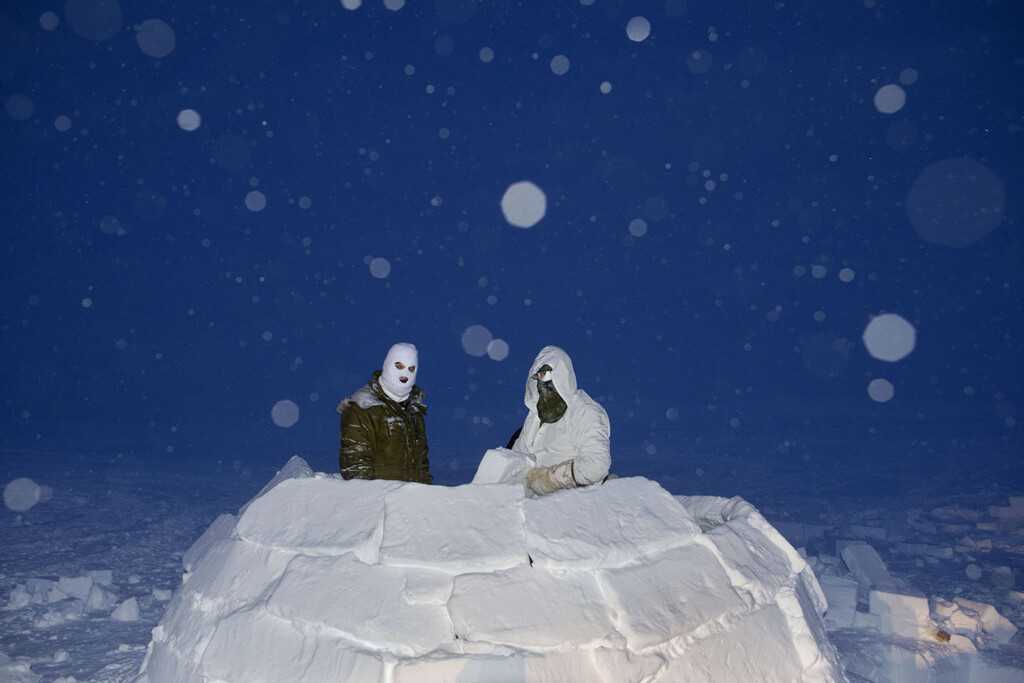

In an extended conversation with GUP, Palu reveals details about his experience documenting the gradual militarization of the far North for his project Distant Early Warning, and how he dealt with the many challenges that come with photographing one of the most inhospitable regions on earth.

To start off, what was it that personally drew you towards the Arctic?

I am from an Arctic country: the Polar region and being cold are both a part of my identity as a Canadian. The Arctic Circle is an imaginary line defined for now by temperature; soon, we will need to rethink where the line that separates the Arctic from the South really is. The landscape of Canada is mostly inaccessible, in which the Arctic makes up nearly forty percent of the landmass of the country and is one of the coldest places in the world. I was not drawn to the Arctic, but rather wanted to more deeply examine and express ideas that are a part of my identity, and how in photography and for geopolitical purposes people invent narratives. My first trips to the North started in 1991 and extended to James Bay and the Northwest Territories. The Arctic is many different things and places: it is not one thing or one place, but 100 different places.

The Arctic is one of the most inhospitable places on Earth, and I can imagine that there was some form of rigorous preparation — both physically and emotionally — involved before you made your way there. Could you elaborate on your experiences with the process of readying yourself for this long-term project?

I like feeling cold, wet and uncomfortable — this evolved out of my childhood where I followed my father on the land hunting and ice fishing. The most important preparation and education for this project was seeking out Inuit elders who taught me about the land, their history and science. Logistically, there was a lot of planning and preparation for this project, because for much of the fieldwork I went to places beyond the mainland of Canada and Alaska — into the high Arctic and across the ice on the Arctic Ocean. There were many areas where there were no roads, no buildings and no cell signal.

“I quickly learned to embrace the environment and see the beauty in being cold. At the end of it all, what you realize is that nature is the ultimate power, and it is something to be respected.”

If something went wrong, which in the Arctic can be everyday, one needs to be physically resilient and prepared. In one case I had to pass a test where I walked on a frozen lake where the air temperature was minus 36 degrees Celsius, walked out to an open hole in the ice and into the water, waited at the edge of the ice neck deep in the water, then pulled myself out of the lake, changed my wet clothes to dry and warmed myself back up. The key part of the test is psychological, and to not panic in those conditions. In the high Arctic, if you are on the land and your snowmobile goes through the ice, you need to remain calm, know how to recover yourself and/or the people you are with or you could die. I quickly learned to embrace the environment and see the beauty in being cold. At the end of it all, what you realize is that nature is the ultimate power, and it is something to be respected.

Can you elaborate a bit on some of the logistical challenges you faced due to the effect of the extreme cold weather?

The average winter temperature I worked in was minus 50 degrees Celsius, sometimes lower. In the Canadian Arctic everything happens slowly and many times not at all, because the weather prevents it, you can’t get to something or someone, or you are exhausted. Getting dressed with your outside clothing can take up to 15 minutes. Batteries die quickly, for which I carry 10 inside my parka (heavy winter coat), the vapor from your breathing can form ice on the back of your camera and all over your face. In some cases my eyelashes have frozen together, and on one trip I scratched my cornea wiping ice away from my eye, forcing me to wear an eye patch and use my non-photo eye to see and work with.

Another challenge is, if you go from outside at minus 50 degrees to inside a heated building your gear will fog with condensation and be unusable for sometimes up to 1-2 hours. Some locations can take up to 4 days to travel to for a 3-4 hour window of photography before you have to leave. At the end of it all, the isolation can take a heavy psychological toll in the winter months when nearly the entire day is in darkness. I like working in the extreme cold — I feel comfortable in it. The hard part is dealing with boredom, sleep deprivation from travel and waiting for days in a tent during storms. The way I have coped is I have learned to meditate and read a lot, but when that doesn’t work I’ll go outside for a walk in circles around the camp in the snow and use my imagination to pass the time.

“At the end of it all, the isolation can take a heavy psychological toll […] The hard part is dealing with boredom, sleep deprivation from travel and waiting for days in a tent during storms.”

You have been documenting the Arctic for some five years now. What observations have made during your time there, concerning the exponential transormations taking place there, regarding geopolitics and climate change?

I first travelled to the Arctic in 1993 when diamonds were discovered in the Northwest Territories. All my work in the 1990’s was connected to mining and resource extraction. In 1993, when I arrived in the city of Yellowknife — known as a hub for traveling North just below the Arctic Circle — I was confronted by striking gold miners who had been on a year-long violent strike against a mining company. It was a very tense situation, because a year earlier someone had planted a bomb in the mine, killing 9 miners, which taught me that the Arctic is not only a vast empty pristine space filled with animals. There are forces both commercial and geopolitical in nature that are in play, but are largely unseen, so we don’t know about them because of other dominant or invented narratives.

To your question about climate change, I can share what the original scientists of the Arctic, who are the Inuit, are telling me. What I am hearing is that the length of seasons is changing drastically and rapidly and for the worse, and that animals are not behaving as they once did. I have also been around a lot of what would be for us conventional scientists as well. From the data I have been shown, all governments need to act on the forces that are deteriorating our ecosystem as a stable environment which is required for life on our shared planet. Nature is the ultimate power, the planet is strong and will always survive, but it’s the conditions that we need to survive that we are destroying.

What I find particularly intriguing when looking through your photographs, is the extent to which soldiers — Canadian, American, UK, French — operating in the area rely on traditional Inuit knowledge and technology for their survival. I wonder about the power dynamics between this exchange of knowledge, and whether that was ever a question in your mind when you were in the Arctic.

This is a complex issue on which I could write pages of history and observed experiences. What I have learned from my Inuit teachers is that human beings have no power really — it is our own invented narrative that we have power. Anyone who goes to Canada’s high Arctic is faced with the raw reality of having to survive as soon as you set up your tent on the land and can’t stay warm or heat your food. Wind, temperature, snow and ice are beautiful and are forces to be respected, and they can tell you things. The ice, snow and animals can speak to you and tell you what’s going on: you only need to listen.

The Inuit are the voice of the far North, and anyone who doesn’t listen or understand the place gets hurt quickly with frostbite or is evacuated off with some weather related condition. It’s one of the only places where the air can kill you by freezing you to death.

Canada is the only country, which in any recognizable scale incorporates indigenous knowledge into any Arctic military program. The Canadian government has a long colonial history with many recorded cases of abuse all over the country. Sadly, the Arctic has its own dark history when it comes to the colonial era and early militarization during the Cold War of Indigenous people, and the communities in the Arctic each have their own story. I have tried where possible to incorporate some of the complex layers of how the Inuit are a part of this story.

“… it is our own invented narrative that we have power. Anyone who goes to Canada’s high Arctic is faced with the raw reality of having to survive […] The ice, snow and animals can speak to you and tell you what’s going on: you only need to listen.”

How does your experience documenting the increasingly tense political situation in the Arctic — which many have taken to calling the ‘New Cold War’ — differ from your experiences with other projects, such as Road Through War, and The Kandahar Journals?

The Arctic is a complex place that is very diverse: geopolitically, it is like a chess game instead of an actual war zone. The region is massive and exists within an invisible line defined by temperature that we call the Arctic Circle. The geopolitical tension over the Arctic is actually not happening there but rather in the media and in the southern capitals of nations looking to secure an imaginary slice of imagined resources like oil, mining or shipping routes. That is essentially what this project is about, which is the unknown. All of these layers and perceptions are based on imagined and invented narratives, related to the legacy of the Cold War. When you look at the details in my photographs and reflect, what you’ll see is impossibility and emptiness. The natural features like ice, mountains, temperature, water and darkness are what will defeat you, because there never is any real enemy to fight, except ourselves and our own imagination.

“The Arctic is a complex place that is very diverse: geopolitically, it is lie a chess game instead of an actual war zone.”

‘Distant Early Warning’, the title, is taken from the name of the radar line stretching from Alaska to Greenland, warning of impending bomber or missile attacks over the Polar Region. The word “impending” here strikes me as crucial, especially given the unpredictability of how global warming will truly affect this region. Could you tell us why you chose this as the title for your project?

The DEW Line or Distant Early Warning Line is now called the North Warning System, and has been operating for nearly 70-years based on an imagined attack on North America via Alaska, Canada or Greenland. There is a secret, but partially not-so-secret history of dueling Russian and American nuclear submarine operations under the ice. This should remind everyone that science can be used for both positive and negative purposes. Also, sailing below the ice allows for stealth using submarines, which can also be used as listening devices and espionage. Which brings me to my next point, which is that this project is also about communications by seeing and hearing. The Arctic is massive, it can’t be thought of like a country, so it can’t really be defined in any one way. Depending on how you look at it, up to the Second World War it was an impenetrable wall of ice. The Finns and Russians used weather and Arctic conditions as part of their strategy to defeat Nazi Germany in what was the first conventional war in the Arctic. Centuries earlier the Vikings conducted some of the first Arctic military operations and used the fjords in the North as hidden near Arctic bases. There are many ways to look at geopolitics in the Arctic depending on who is creating the narrative.

You mentioned in an interview with The Globe and Mail that it took you three years to capture the beautiful shot of US Army soldiers parachuting down to Fort Greely, Alaska — which you describe as an encapsulation of the project’s larger message of human beings trying to overcome nature in a place where nature is in complete control. Could you elaborate a little more on the story behind this shot, and the experience of capturing it?

The most important part of that photograph is not the parachutists, but the mountains in the background. A mountain is stronger than any tank or army, and trying to defeat or overcome a mountain or what it represents is impossible. That is a layer to this project, which is the absurdity of it all. That photograph is also a contrast between the beauty of nature and the intentions of some human beings or governments. A snowstorm can destroy any army, but no army can destroy weather — you must work around it because it is the true power on earth. Getting that photo took years because I had to rely on chance, weather and the positioning of the soldiers and airplane, of which I have no control over. I kept going to parachute drops for years until I found the idea I needed to express.

“A mountain is stronger than any tank or army, and trying to defeat or overcome a mountain or what it represents is impossible.”

You also speak of the profound importance of human connection in the Arctic. Could you tell us about the relationships you had with the people you were teamed up with?

There are times when you are on the land for weeks and going from one community or campsite to another when it’s dark for 20 or more hours a day. This can result in you feeling cut off from everything and everyone. In many places there are no ways of communicating to the outside world. Trust is an important thing when you are out on the land — you always have to be with people who have critical knowledge and experience. Small mistakes can have a big impact and count for a lot when you have nowhere to go in an emergency: there were no hospitals in many of the places I worked in, and actually sometimes there is nothing around you at all but fields of snow and ice.

When you are sleeping and someone is on fire watch, you trust they won’t let the tent catch on fire, which when it’s minus 50 degrees Celsius could be catastrophic. Also, sometimes you need someone to be on predator watch looking out for polar bears; they need to know what they are doing and know how to use a firearm safely.

“Trust is an important thing when you are out on the land — you always have to be with people who have critical knowledge and experience.”

People were killed by bears, including boats and ATV accidents near where I had worked. Your snowmobile could break down, or you could fall off the back of a snowmobile without the driver realizing it, and then you are lost on the land (this nearly happened to someone on our trip). One of the most memorable moments was with one Inuit elder I spent time with who pulled our boat up to a swimming polar bear and talked to it as it swam beside us. Something many photographers don’t talk about are their relationships with photo editors. I started this project on my own with a Guggenheim Fellowship. Then, National Geographic magazine partnered on it and Sadie Quarrier was my main photo editor, who reviewed every one of the over 150,000 photographs I took, along with Sarah Leen who both challenged me in new ways and gave me creative tasks to find images to explain the complex themes of this often misunderstood place.

Finally, do you think your experience in the Arctic has changed how you now approach documentary photography?

This project was another part of my evolving and changing idea around documentary photography and how it can be more than only a print or jpeg. Before this project I published a series of newspapers and a book (Front Towards Enemy, Yoffy Press 2017) that the reader could deconstruct, really take apart and re-edit the narrative. When I was researching this project I came up with an idea based on a doomed expedition in the Arctic in the 19th century in which the camera was never found. So I created an installation for the SXSW Festival of large prints frozen in large ice blocks that melted over the course of a few hours outdoors as a statement on climate change. It’s ideas like that that I have embedded into the deeper themes of this work like signaling, the body, technology, temperature and the power of nature that are experiential elements in the photographs.

‘Distant Early Warning’ was supported by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation & Pulitzer Center. All images in the slider have been generously provided courtesy of Louie Palu ©. For extended captions of the images in the slider otherwise unmentioned, please visit the photographer’s website.