In his series Platforms, New York based photographer Natan Dvir (b. 1972, Israel) reveals the city’s subway culture through an almost painterly study of underground architecture and body language. Set within the frames of subway columns, each image is composed to give a larger narrative to a single moment; each platform portrays complex dynamics between seemingly unrelated passers-by. GUP had the chance to talk to Dvir about ‘non-places’, the influences of historical art on his photography and the complexity of modern day social isolation.

How did your interest in capturing New York’s city life began?

I first came here in 1997 and immediately fell in love with the city. I was working in computer science and economics but always had a thing with photography. So, a couple years later I bought a book and a camera and taught myself how to photograph. I almost automatically went to the subway to test my gear since that place had always fascinated me. But, no matter what I tried, I never felt that it was adding something to the conversation. There’s so much work that’s been done in the New York subways and I wondered what I had to say differently. Then, I thought of the subway as a place of transition and that’s kind of where it all started.

What did you find so interesting about the idea of ‘transition’?

When I was building my artist’s statement, a friend of mine pointed out the term ‘non-place’. It’s a concept developed by French anthropologist and philosopher Marc Augé that refers to places of transition, like airports. You don’t realise it’s actually a place, you’re just moving through it. In a place like that, I experienced that people stopped paying attention to themselves, they don’t pretend to be anyone different, they come as they are. I had never realised that this was exactly what I felt when being in the underground; it was a human and real space for me. A place where everything is democratic. It doesn’t matter if somebody has more money, you’re all even.

Your photography overall focuses primarily on human, political and social issues. Did that influence you in this particular series?

Platforms is a combination of things; it’s a visual exploration of the city but particularly about social isolation. Israel, where I come from, is a very warm country. People are friendly and minding each other’s business all day long. In New York it’s the opposite. Nobody is looking at anybody and it’s very inappropriate to invade someone’s personal space. Everybody is in their own little world trying not to meet each other. On top of everything, technology is taking it one step further, it disconnects people like they’re going into space. I always wonder what will happen when people start talking to each other or try to engage a bit more. You would think that in a megacity like this, no one would want to be alone, but it seems like people all the time try it anyway. That’s what baffles me sometimes. What are people afraid of?

Tell us about the types of things you saw or experienced there.

I explored how people reacted to my photography. What I’m doing is actually very voyeuristic. I’m invading people’s lives and portraying them as if they are in their own display window. It was interesting to see what they did to the 1.95-meter-tall guy in the middle of the opposite platform! Some of them hid behind the pillars, left the frame or started to pose, while others started to look around for what it was I photographed, not realizing it was them. It’s amazing to me that we live in the most visual times that have ever existed and people still aren’t completely comfortable with photography.

When I first moved to New York, I would go on the subway and record the time of how long it took me to make eye contact with someone. I found people were just trying to avoid me, and that was so weird. When you’re in Israel in a traffic jam, everybody’s looking into everybody’s cars. It’s not really polite to look, but in New York it’s extremely not polite to look. They will ask you immediately why you’re taking photographs, while in other countries, like in the Philippines, people try to shuffle in front of your photograph hoping you’re going to take the shot. It really depends on the culture and the norm, so I try to be as respectful as possible. I became a bit more sensitive and understanding of the city’s culture over the years.

You composed the images in quite a unique and new way by taking advantage of the geometrical architecture of the underground system. Could you tell us something about your approach?

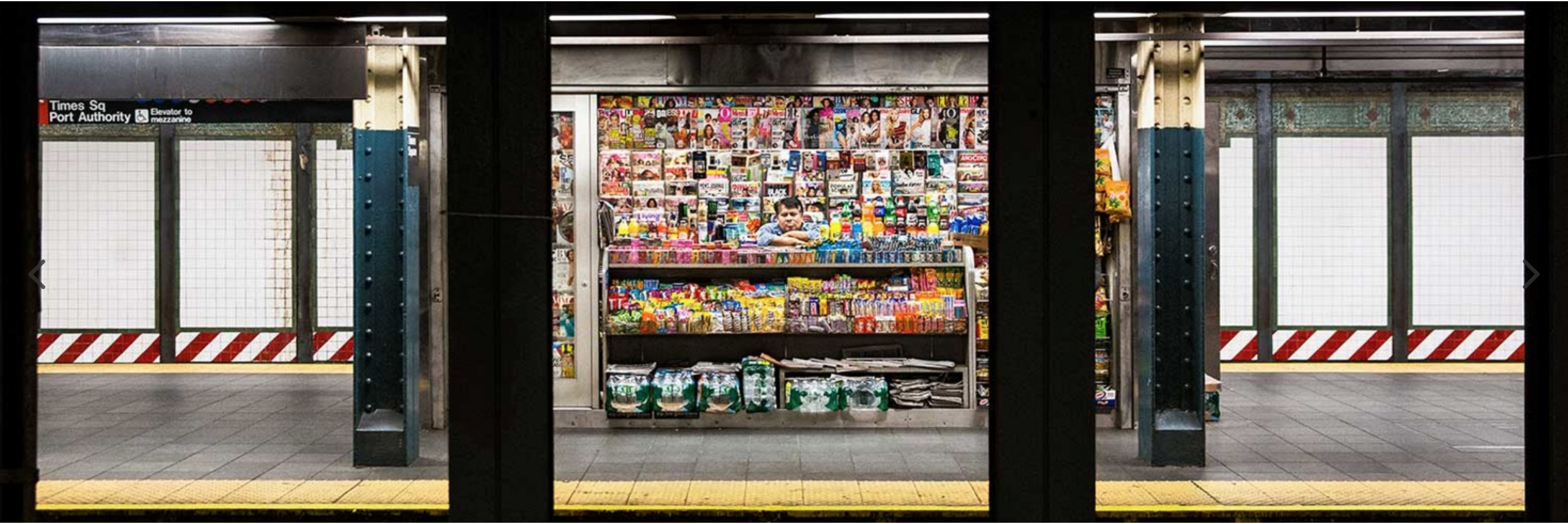

My photographs are based on the different languages of triptychs: panoramas that are build out of three squares. There are different strategies in this type of historical art, which I try to apply in this series. The first strategy is that both sides introduce the centre, which would be the most important frame. Sometimes the centre is empty and the lack of distance is actually the meaning of the picture. In other cases, all panels are equal or there’s a story to be seen from left to right or right to left. You need to understand this specific type of architecture; the social level merges with the architectural level. The graphics of this formula helped me visualize the idea of how people build virtual spaces around themselves. Besides that, the underground feels like a theatre to me. You have this stage at the opposite platform, the actors are coming in and you don’t know what will happen. You try to figure out the play and then suddenly a train comes in and the following act appears.

Considering how unpredictable it all is, how do you create these stage-like scenes?

As I do my research more on an anthropological level, I went to several stations at different times of the day to observe the different types of interactions. Last year, for example, I went to see how Halloween looked at the subway. After spending a long night without an actual scene that blew my mind, two girls dressed like Ghostbusters and a Batman figure walked in, and boom! I had my shot. Another day the salesmen in the kiosk fell asleep. I like those human experiences that you could never predict. The series might look like it’s staged but I could never imagine staging anything like this.