Aaron Schuman (b. 1977, USA) is a photographer, writer, lecturer and curator based in the United Kingdom. In 2019 he published SLANT, a photographic investigation of police reports as featured in the local newspaper of Amherst, Massachusetts: a small, quiet town in New England. SLANT can be viewed as an intriguing interplay of text and image where the concept of ‘slant rhyme’, originally introduced by the 19th-century poet Emily Dickinson, is implemented. In slant rhyme, words that appear to rhyme do not necessarily match verbally, exactly. Schuman uses this idea to loosely weave the mediums of photography and text together in an oblique way.

In conversation with GUP, Schuman reveals the captivating details behind creating this publication, and his perspectives on photography practice and education.

What inspired you to make a project specifically about accounts of speculative crimes?

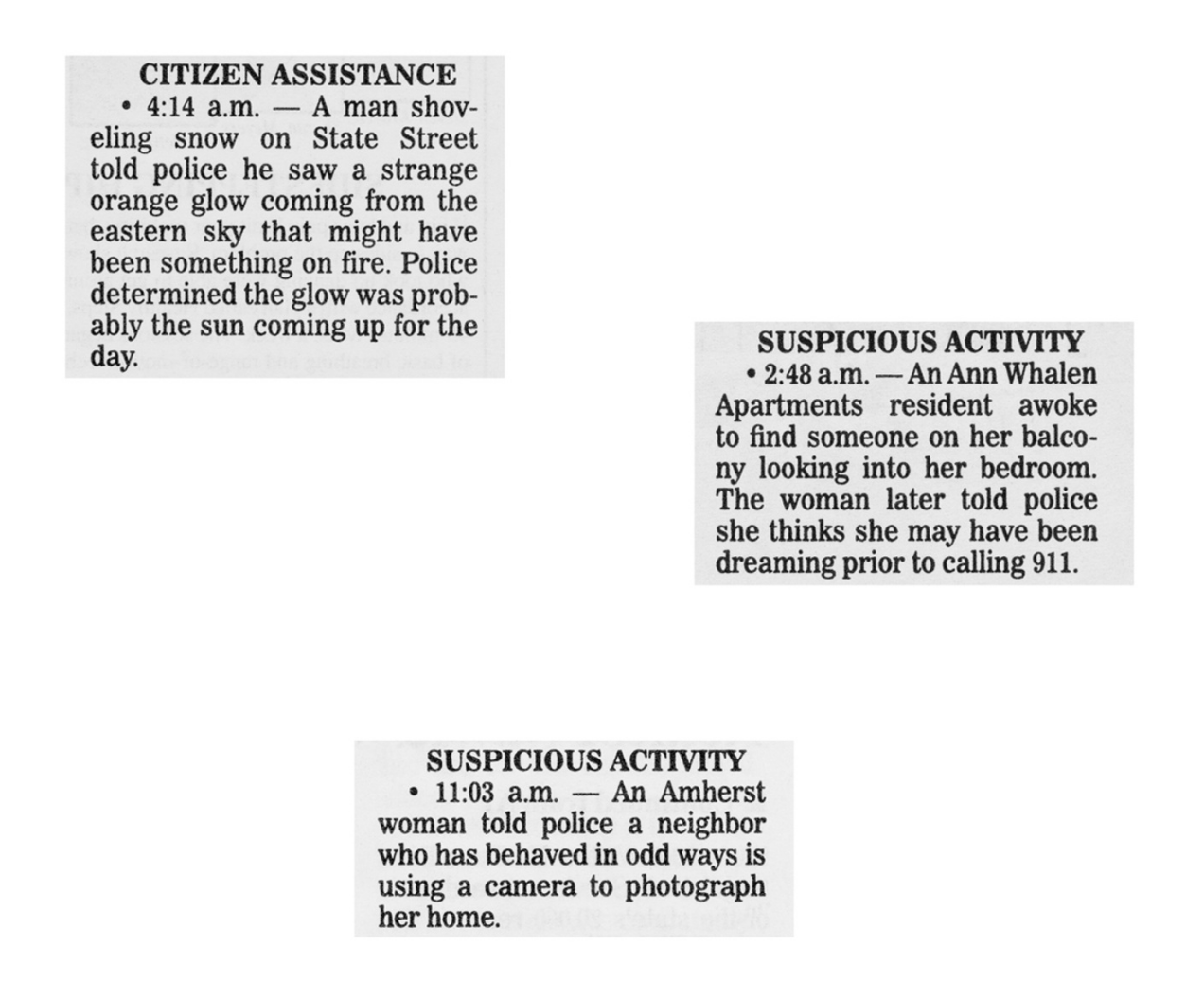

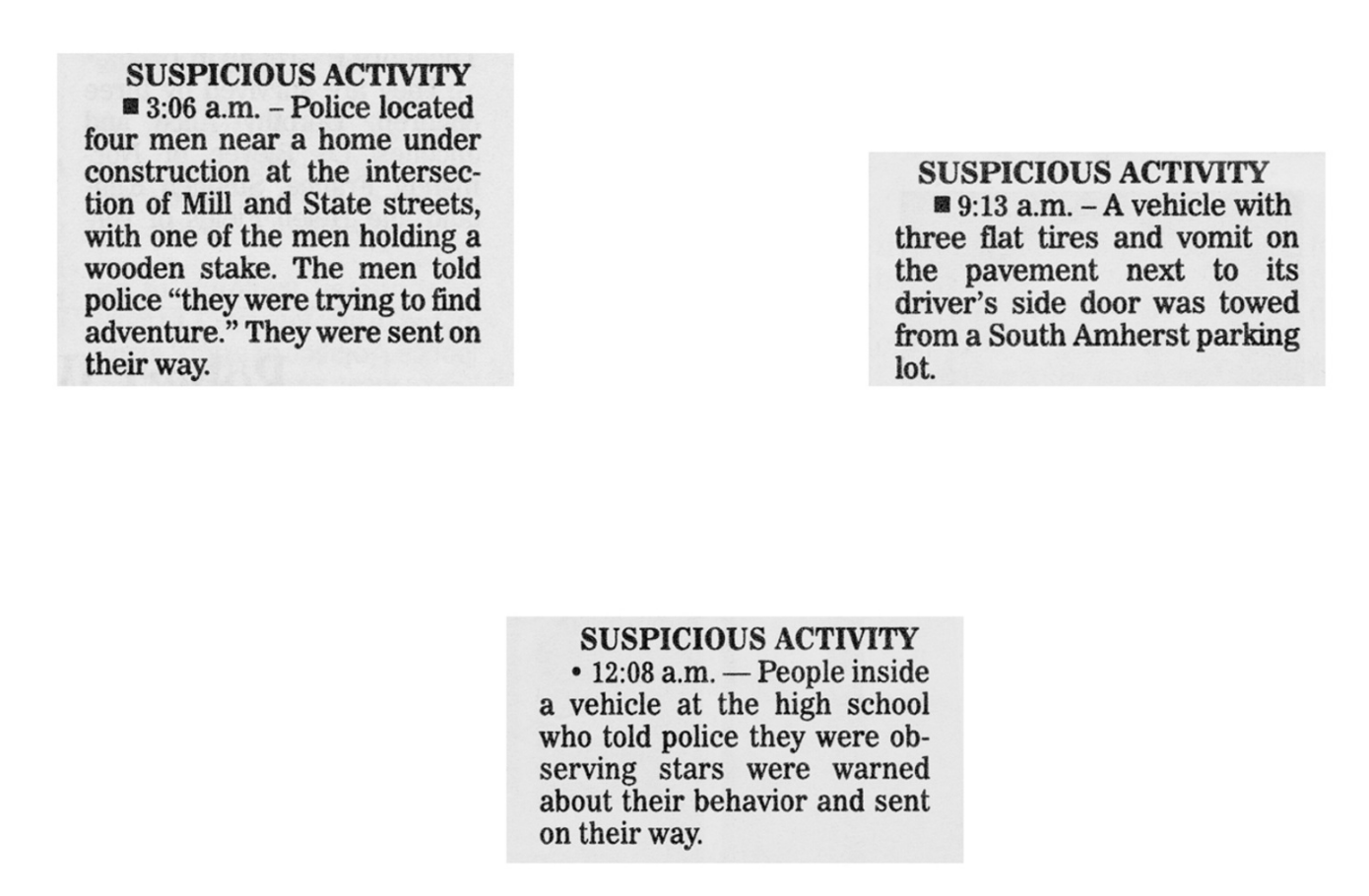

As a project, SLANT began in 2014, when I was visiting my parents in Amherst – a small town in Massachusetts. One day, I saw a copy of their local weekly newspaper – the Amherst Bulletin – sitting beside their sofa, and picked it up to see what was going on around town. As I went through its pages, I discovered a section entitled ‘Police Reports’, where various arrests were listed, and where the weekly activities of the local police were reported. Some of the reports were quite predictable or boring – there was a fight outside a downtown bar, or something like that – but others were really strange and intriguing. And quite often, it seemed that the ‘news’ within these police reports wasn’t really news at all, because nothing had really happened. For example, one read: ‘CITIZEN ASSISTANCE: 4:14 a.m. – A man shovelling snow on State Street told police he saw a strange orange glow coming from the eastern sky that might have been something on fire. Police determined the glow was probably the sun coming up for the day.’ These bizarre reports were often funny, but they certainly didn’t really seem worthy of attention from either the police or the newspaper, and for that reason I was drawn to them, and felt that they contained something really interesting that I might be able to work with conceptually.

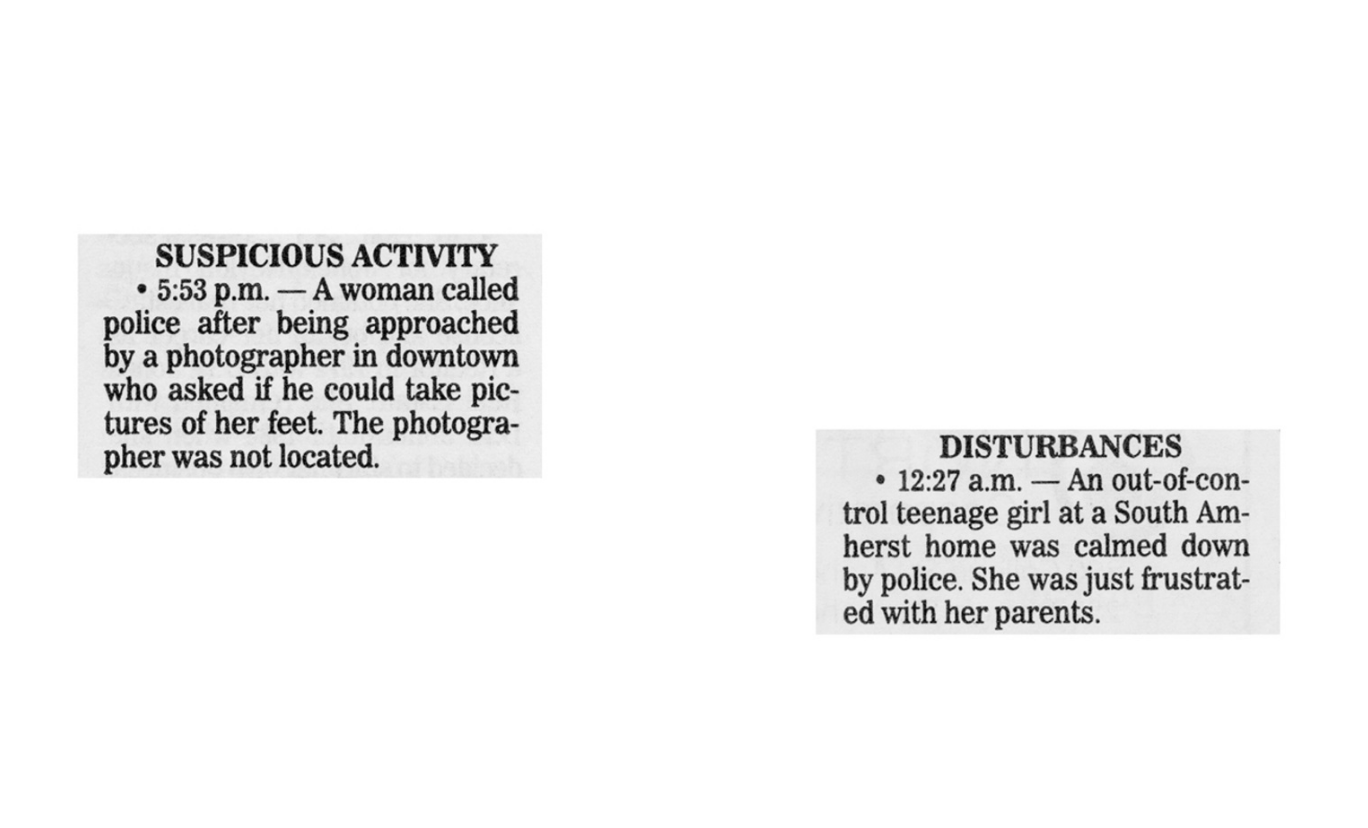

I’ve been living in England for more than fifteen years now, and I was just visiting my parents for a few days at that time, so when I was leaving I asked my dad to collect the ‘Police Reports’ section of the paper every week and send them back to me, allowing me to build a catalogue of these instances. What drew me to them, photographically, was the fact that often when I read the reports, I instantly imagined a visual image of the situation in my head. Also, many of the reports featured the character of a photographer – for example, ‘SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITY: 5:53 p.m. – A woman called police after being approached by a photographer in downtown who asked if he could take pictures of her feet. The photographer was not located.’

(…) I instantly imagined a visual image of the situation in my head.

Do you think that Amherst became an inspiration to you, precisely because nothing much is actually happening there?

Very much so. I grew up in the area – in Northampton, Massachusetts, which is a town only seven miles away – and my parents now live in Amherst. When I was a teenager and just getting into photography, I thought of it as being the most boring place in the world; that there was nothing to take pictures of there. Instead, I was desperate to move to New York City, where all the ‘action’ was happening. It’s rather ironic to me that now, twenty-five years later, when I go back to this place, I find it fascinating. Having moved away so many years ago, and having lived outside of the United States for so long, I now can see all the strange and intriguing details that I hadn’t noticed before.

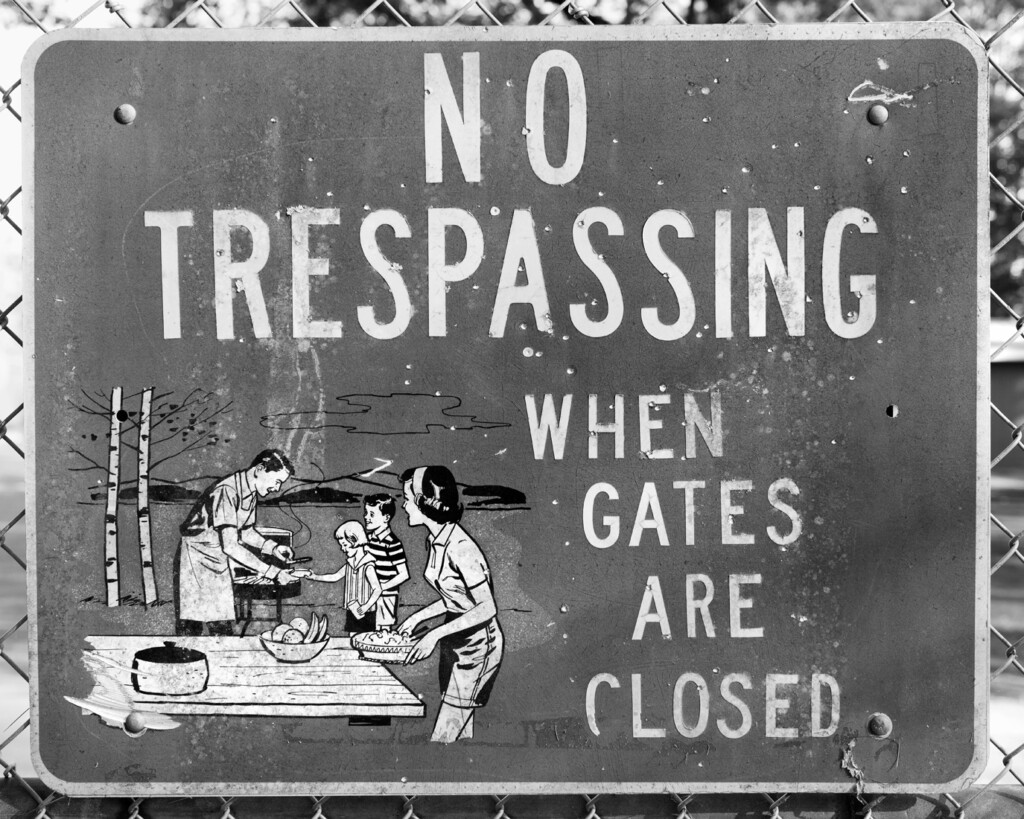

So now, I find the town so inspiring – from the outside it has a quintessential, small-town New England feel, but all these amazingly bizarre things are happening just beneath the surface. Of course, when I showed my parents some of the pictures that I was making while I was working on SLANT, they often asked me why I was even bothering to photograph these things – they pass these things every day, so of course they don’t appear strange to them. But to my eye they’re so odd, and telling, and full of potential meaning.

(…) having lived outside of the United States for so long, I now can see all the strange and intriguing details that I hadn’t noticed before.

Also, in my experience, New England is a part of the States that doesn’t usually get much attention, or is not explored very often in photography. Generally, when photographers are exploring America, they mainly focus on things like suburbia, or urban environments, or the American West, or the Deep South, and so on. I think that because New England is so ‘quaint’-seeming, it often gets overlooked because it’s ‘not American enough’ in that stereotypically twentieth-century way that we’re all familiar with through films and television; it almost seems too sweet and old fashioned to be photographed.

For me, New England is strongly connected to its colonial history and European foundations but it also represents many of the fundamental pillars of American history – wave upon wave of immigration, westward expansion, the search for religious freedom as well as religious puritanism, the conquering and decimation of native populations, the industrial revolution, anti-slavery movements, labor movements, and so on. Many of these both positive and negative aspects that came to define American history and culture originally happened within this small part of the country, and then expanded and became more rampant and accelerated as the country grew. Therefore, although Amherst looks on the surface like this idyllic and old-fashioned place, underneath it lies representations of almost the entire history of America.

Is there a specific reason why you photographed the series in black and white?

Initially, the idea to photograph in black and white came from the fact that the police reports were printed in black and white, and maintaining that form made a lot of sense to me. But part of it also had to do with the nature of the descriptions, and the style in which they are written – no matter how crazy-sounding the reports are, they’re presented in this very deadpan, matter-of-fact and concrete language. Even though they might be describing some bizarre or surreal event (or non-event), they do it in such a flat, black and white way.

Within the history of photography in America, there is a tradition of what’s known as ‘straight’ photography. Photographers such as Walker Evans and Paul Strand were referred to – and referred to themselves as – ‘straight photographers’, and photographed in a very direct manner, mostly in black and white. They employ this unassuming and seemingly objective approach and perspective, and often focus on the most ordinary and everyday subject matter, but there are subtle details within the pictures – or in their sequencing, groupings and editing of these pictures – that hint at what the photographers are actually, subjectively, trying to say. I really like that – this sense of blunt directness mixed with a subtle, multi-layered ambiguity – and therefore I wanted to adopt a similar approach within SLANT, as well as have the work speak to that particular approach and history in photography.

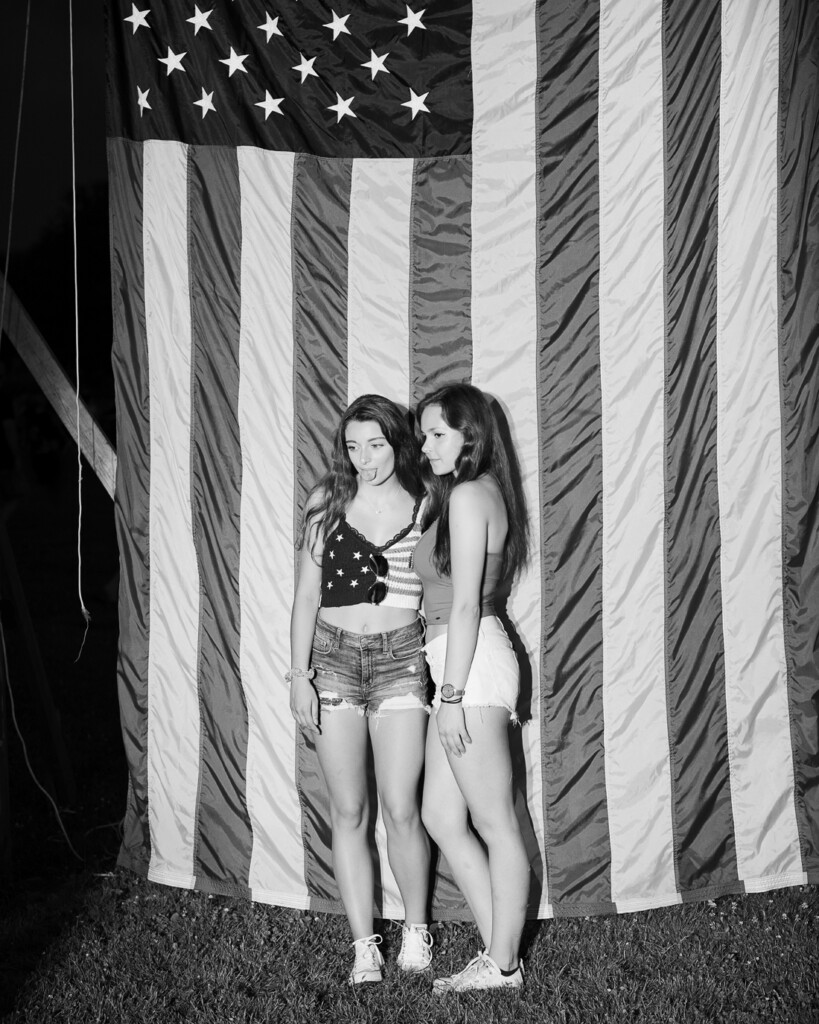

And lastly, I think that as a country, the visual representation of America came of age in the mid-twentieth century – alongside the rise of advertising, Hollywood films and television – and therefore within contemporary visual- and pop- culture it has mainly been described and defined in colour. In our shared visual imagination, America is often seen with this slightly over-saturated, glossy, almost sickly-sweet cinematic neon glow. I wanted to quiet that representation of America down a bit, and instead look at aspects, details and so on that might otherwise be overwhelmed by colour, and all of the cultural presumptions and visual baggage that comes along with it.

(…) America is often seen with this slightly over-saturated, glossy, almost sickly-sweet cinematic neon glow.

What relation do you see between photography and text in your work?

At the beginning of the project, my first instinct was to pair the texts and images together as diptychs, making photographs directly related to each individual police report. For example, I have a photograph of a giant foot, which aligns perfectly with the report about the photographer wanting to take pictures of someone’s feet. But after a while I realised that this was imposing limitations on both the photographs and the texts, because from the viewer’s perspective, it insisted that you read the relationships between the texts and photographs in only one way. I started seeing that one photograph may actually bear a variety of interesting relationships to several different reports, and that one report might bear a variety of different relationships to several photographs. So relatively quickly – about a year into the project – I abandoned the strictures of the diptych approach, and began to try to find ways to pull the two mediums apart, making the photographs more loosely related to the texts, and vice versa. And that’s when the concept of ‘slant’ came in.

One of Amherst’s greatest claims to fame is that it’s the hometown of the nineteenth-century poet, Emily Dickinson, who’s former home (which is about a five-minute walk from my parent’s house) is now a museum entirely dedicated to her. While I was making SLANT, I visited the museum, and during the tour the guide gave an excellent explanation of how Dickinson incorporated ‘slant rhyme’ within her poetry. In poetry, ‘slant rhyme’ consists of having two lines in a poem end with words that almost rhyme, but don’t, creating a sense of dissonance – or a ‘slanted’ relationship between them. When he said that, it was a bit of a eureka moment for me, as this slightly off-kilter, ‘slanted’ relationship seemed like the perfect way to think about text and image within this project.

Would you say that SLANT has a socio-political undertone when taken within the context of American politics?

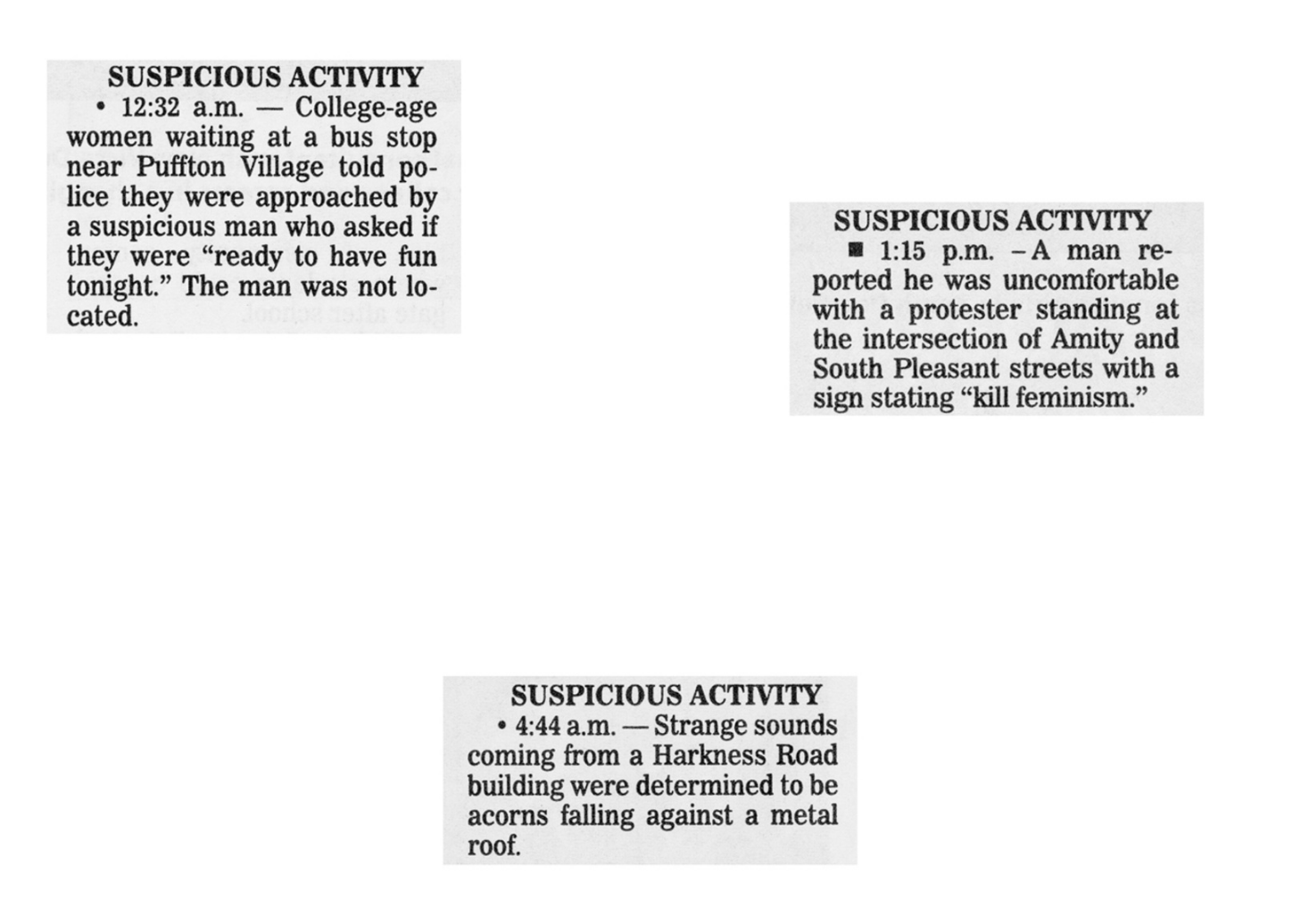

Yes, definitely – but in a rather subtle way. At first, the project was intended to be a loving and light-hearted, slightly ironic take on the place where I grew up. However, when I started to gather together all of the material and looking at it collectively, I began to see that there were quite a few themes arising that were disturbingly serious, and especially pertinent to the times in which the project was being made.I embarked on the project in 2014, just as the campaigning for the 2016 American election was kicking off, and finished the project in 2018, two years deep into the Trump administration.And the themes that I noticed being hinted at within the material collected over this period of time included a rising sense of paranoia, xenophobia, misogyny, misinformation, and so on. All of these themes that were arising and bubbling up on the surface made me realise that my project was actually more serious and politically charged than I originally intended it to be.

Furthermore, for me it was especially strange to observe these themes arising in this particular part of America, because western Massachusetts is extremely well known for being one of the most left-leaning, liberal and progressive regions in the country. There are many universities, students and academics based in the area; ‘hippies’ and countercultural movements flocked there in the 1960s (not to mention in the 1860s and 1760s) and have been present ever since; there are longstanding traditions of feminist and political activism that originate in the region; there’s a long-established and thriving LGBTQI+ community (according to Wikipedia, my hometown – Northampton, Massachusetts – ‘has the most lesbian couples per capita of any city in the US’), and so on. On that basis, as well as on my own experience of the place as a child, I’d always thought of it as very different from the stereotypical clichés associated with American culture and politics. The realisation that, today, reflections of the darker sides of contemporary American culture (and humanity in general) are starting to bubble up to its surface became quite disturbing to me. Nevertheless, I only came to understand these political undertones once the project was already well on its way, so they played more of a role in terms of the editing, sequencing and underlying structure of the book rather than in the making of the work itself.

Thank you very much for disclosing intriguing details about your publication SLANT. Now, I would like to ask a few more personal questions concerning your diverse career and hybrid approach to photography. As Programme Leader of MA Photography at UWE Bristol, what advice do you give to students who aspire to pursue a career in photography?

I’ve been working as a Senior Lecturer in Photography at various British universities since 2005, and about three years ago I was invited to join the team at UWE Bristol in order to help to design, establish and deliver a new post-graduate programme in MA Photography. In many ways, our programme at UWE Bristol is designed with a ‘hybrid approach to photography’ in mind, in that from the outset students are encouraged align creative experimentation with in-depth research, in order to identify not only what kinds of pictures they want to make, and what subject-matters, aesthetics, ideas, histories, theories, concepts and strategies that they are genuinely interested in, but also to identify how they might creatively approach these things in a way that is true and unique to themselves. Then, once they’ve conceived of and produced an extensive body of ‘personal’ work using these strategies, they are asked to think creatively about how to contextualise and disseminate this work (and themselves and their practice at large) within a wide variety of contexts and disciplines that are well-aligned with their work. I think this self-searching process is a crucial pillar in the students’ creative development, as it helps them to reflect on themselves, their work, their ideas their perspectives, their ambitions and their careers in a profoundly holistic way.

In today’s culture, it can often feel like everything has already been done. Very regularly, when someone is pitching an idea for a project to me, I can easily point them to at least three or four different photographers, past and present, who have or are working on projects along similar lines. This is not meant to be discouraging in the sense that I’m saying, “It’s been done”, but rather is intended to be encouraging in the sense that they can explore the diverse variety of approaches that other practitioners have taken in order to make a common theme meaningful and individual to them, and take inspiration from that. Also, for photographers who are just starting out, it is very easy to feel pressured to mimic or imitate a certain type of photography, or certain trends in photography. Therefore, I think my main words of advice to students would be to really identify and understand themselves, their own perspective, their own practice, and to then use this to explore the world, express oneself, and engage with photography in their own unique way.

“In today’s culture, it can often feel like everything has already been done.”

Another piece of advice that I have for photographers just starting out is to understand that their journey may last a lifetime, and photography is more rewarding if you see it as a ‘long game’. In other words, it a marathon, not a sprint. Being a photographer is a life-long pursuit. Besides being dedicated to this medium, the community and the profession, you also need to be patient, resilient, proactive and have the confidence to put yourself out there. The process of trying to get your work out there often results in rejection or criticism, but those are learning experiences as well, so take advantage of them, and don’t be in a rush. It takes time to grow and build, to mature, and to find your way.

Do you think it is important to study photography at an academy or not necessarily?

Of course there are many great photographers who never studied photography, so no, it’s not absolutely necessary. But I do see photography education as an opportunity to not only advance one’s own work, but also to gain an in-depth understanding of the culture of photography – it’s histories, theories, meanings, possibilities, relationships to other fields, contemporary developments, and so on – and personally, exploring these things is both important and inspiring to me as a practitioner. Photography education allows for engagement with photography not only as a maker, but as a member of a cultural community; people can learn and gain a lot from trying to make work while also exploring the landscape and history of the medium that compels them alongside others that are similarly invested.

“Photography education allows for engagement with photography not only as a maker, but as a member of a cultural community (…)”

Certainly, you can also explore all of these things independently – but if you are in an environment where you are surrounded by people that are truly curious, engaged and excited about the same things you are, and are participating in that culture and community on a very regular basis, it’s inspiring and can certainly help in advancing one’s work.

How did you experience your photography practice as a fresh graduate and how has this changed in the past years? Are there any mistakes you regret now or wish you would have avoided at the start of your career?

The biggest change I encountered during my photography career was the transition from an analogue to digital culture – and I’m not just talking about cameras and technological advances. Also, I graduated university in 1999, which was really the last moment when there was any semblance of a stable financial market for photography; for being able to imagine a secure ‘staff’ job in photography.That said, the rise of the Internet has also introduced huge possibilities in terms of engaging with and disseminating work; all of a sudden there were so many new avenues, contexts and formats. Hence, while some opportunities closed down, many new opportunities emerged.

In terms of the mistakes I made early on, I was initially chasing other people’s careers, especially those of photographers I admired, and at the beginning tried to replicate what they did. I quickly learned, however, that I needed to find my own path on the basis of what I want and need and love, instead of trying to pretend to be someone or something I’m not.

The other thing is that, when I graduated from university, I suddenly felt that I was in a very competitive environment, and was all alone. But within a couple of years, I understood that I didn’t need to operate totally independently in such a strenuous environment, but rather I could engage with, collaborate, and become a proactive and supportive member of the photographic community. I realised that one person’s success doesn’t result in someone else’s failure; in fact, if one of us succeeds in making or doing something great, we all benefit. The biggest mistake is to feel that you’re on your own. Instead, you can support and help one another while building a culture and career, in a community that is collaborative and positive.

“The biggest mistake is to feel that you’re on your own.”

You were the founder and editor of SeeSaw Magazine, which existed between 2004 and 2014. What has this experience brought to you? And why have you stopped producing further issues?

Three or four years after I left university, I began SeeSaw Magazine – which was basically me saying that I was sick of this competitiveness, that I loved and admired the work of many other photographers, and that I wanted to support, celebrate, and share their work with the photography community and the wider world. Many of the photographers that I included in the first few issues of SeeSaw were completely unknown at the time, and were often simply friends from university, or people I met through the photography community. When I first moved to London in the early-2000s, I joined a photo-collective called PhotoDebut, which was really just a bunch of struggling photographers in their twenties who were trying to build a collaborative network that supported one another and worked together – and they would often appear in the magazine. In fact, the first issue of SeeSaw features Richard Mosse and Esther Teichmann, both of whom were a part of the collective, and like I said, were completely unknown at the time, but have since gone on to make incredible contributions to photographic culture. And I still collaborate with many of these people to this day, more than fifteen years later – a few of them are still some of my best friends – so like I said before, it’s a long-game for sure, but one that it incredibly rewarding if you join forces and work together with others.

Anyway, over the years the magazine’s reputation grew – it was one of the earliest photography magazines that was presented exclusively online, so various people in the photo-community took notice –and it led to many other incredible opportunities for me: to write about photography for books and magazines, to interview photographers for other publications, to curate exhibitions for various festivals, galleries and museums, to teach at various universities, and so on.Also, within those ten years I also got married and had two children. So by 2014, my life was incredibly busy – in many ways thanks to the multitude of opportunities that I’d had via the magazine – but I no longer had the same amount of time to dedicate to the magazine, and I felt it was time to move on; ten-years seemed like a pretty good run, and a good landmark at which to stop…but you never know; I might bring it back one day!

On the 3rd of February, you will be speaking in Amsterdam. Could you please briefly tell us what the attendants can look forward to?

Yes, on the 3rd February, at Pakhuis De Zwijger, I’ll be presenting and artist-talk, followed by a Q&A and book-signing. The talk itself is going to be specifically about SLANT – where it came from, the research behind it, the process of making it, what influenced it, and what it represents and means both personally and culturally. In short, it will be an in-depth, enlightening and entertaining exploration of SLANT, and more generally beneath the surface of the contemporary American psyche.

You can register for Aaron Schuman’s upcoming talk and book signing here.