Anna Ehrenstein (b. 1993) is a visual artist with German-Albanian roots and in her work, she generally reflects on a migration-related visual and material culture in the digital age. Her oeuvre ranges over many different media and is mainly centred around forms of installation and writing – through which she examines the crossings and divergences of ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures and their socio-economic and political entanglement.

In this interview with GUP, Ehrenstein talks about her multidisciplinary project ‘Tools for Conviviality’ – for which she recently won the C/O Berlin Talent Award 2020. This multi-disciplinary artistic work consists of a photography series, an installation and a 360° video. It is based on a collaborative visual and oral research conducted together with Awa Seck, Thibaut Houssou, Nyamwathi Gichau, Lydia Likibi and Saliou Ba.

The project was originally inspired by the Croatian-Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich (1926-2002), who was a critic of the institutions of modern Western culture. His same-titled book ‘Tools for Conviviality’ (1973) deals with the use of technology in relation to the field of education, infrastructure and other socio-political fields in Western environment. Ehrenstein considers Illich’s writings as still relevant regarding the way the systems and technologies to which he refers are applied by human beings today.

What initially started the project and why did you choose Dakar as your destination?

It all arrives from a mix of coincidence and destiny. I was very annoyed by the biased narrative on migration within Western media. At the time of starting the project, I worked for the Berlin Biennale and one of our curators did her PhD on the performance scene in the ’80’s in Dakar. Through further conversation, I found out that the city has lose entry regulations, providing the possibility to work there without needing a special visa. Afterwards, I decided to visit the Dakar Biennale where also work of good friends of mine was presented. I started contacting people and went to see the city during the biennale to check who is up for collaboration.

How would you describe your way of working as an artist?

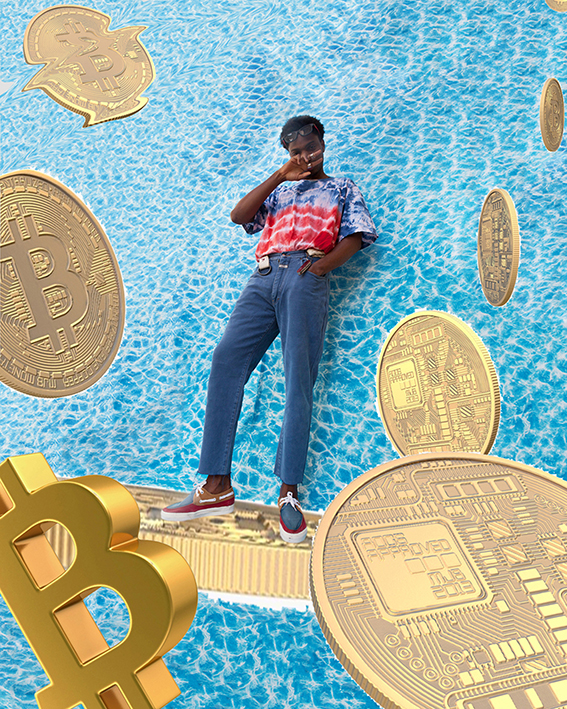

I usually work in research-based work cycles that are multidisciplinary and usually contain photography or video in some fashion. The actual way of producing works is always adjusted to the project and varies heavily. For ‘Tools for Conviviality’, each collaboration I initiated was based on a process-based partnership. For example, since we could not be in a physical space at the same time, “yoga warrior” Nyamwathi came up with the idea to send me to places in Dakar she would visit on a date with herself. Afterwards, I sent her a collection of photographs which she then edited. From that, and her online instructions, I created collage works.

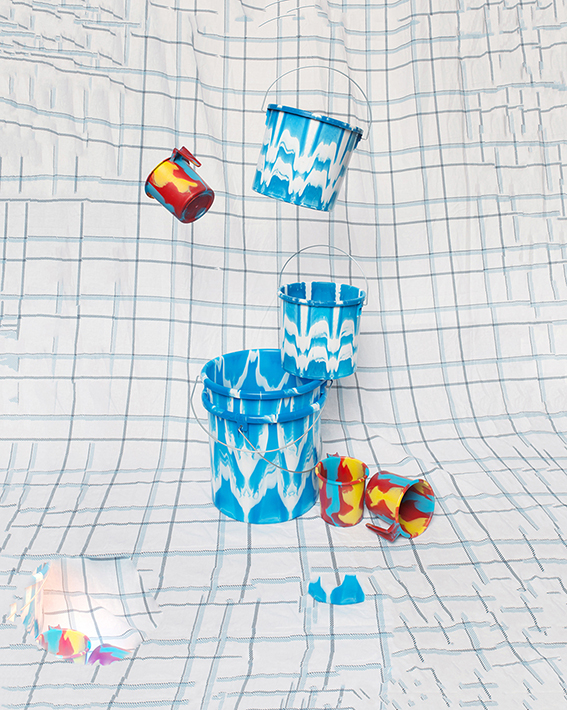

Or, to give another example: members of DONKAFELE, a fashion collective, went with me to the fabric districts in Dakar to choose the backgrounds and objects for the stills, and in return I made images they could use for themselves – for their own purposes. Now we are working on a small up-cycling collection together, that is based on my photographic work. In general, very important for this project was having some ideas of my own and then listening to the better ideas people had around me.

The whole process was coming together as a big hybrid: documentary practices like interviewing, together with staging, applying digital and physical collage practices, 3D rendering, stocks and cheap glitch apps, etcetera. If I can’t pay the people that I am working with, it’s substantial to find alternative ways in which our creative processes can be mutually beneficial.

“If I can’t pay the people that I am working with, it’s substantial to find alternative ways in which our creative processes can be mutually beneficial.”

Would you say that collaboration is a key element for creating socially engaged work?

Yes, for sure. The art market is based on the aura of an individual establishment, but I do feel that Eastern ideas of collective knowledge better align with how societies actually work. Simultaneously, I do not think it is possible to represent anyone else than yourself. If an artist or a journalist or whoever is trying to speak about issues that are aligned to social occurrences outside of their own experience, horizontal hierarchies and collaborative models should be the basis of the exchange. We all have major biases inscribed into our cultural DNA’s, but without collaboration you won’t surprise yourself or anyone else with your findings.

As you describe, your project is “a collection of visual ephemera about the usage of tools for various modes of human togetherness.” How do you see your project functioning now, during the global outbreak of the coronavirus?

I think this global madness is actually a good time to read Illich’s words and remind oneself that digitised tools per se are not the solution of our problems. But they can assist us to design our systems around truly globalised well-being. Covid-19 is urging us to strengthen debates on basic global healthcare and basic global income while it is hitting the already vulnerable among us much harder than anyone else. What we see now is that forms of remote education and work are possible, not completely impracticable, as schools and employees have insisted on previously. At the same time, it is infinitely scary how the conversations around the virus support xenophobic ideas, racialize disease and feed the mouths of fascists in times of horrific economic imbalance.

When I started the project, I was just mostly interested in how creative producers think about and use tools for their own techno-migrational journeys. But the virus keeps in check that these are questions of global significance. How, for instance, can we deconstruct our current application of digital tools to find more sustainable forms of communal understanding instead, in these mad times?

“(…) it is infinitely scary how the conversations around the virus support xenophobic ideas, racialize disease and feed the mouths of fascists in times of horrific economic imbalance.”

In your work – a vivid colour palette, an abundance of patterns and flying objects in the air, while also including a pinch of irony and humour – one can sense an underlying critique of the current system of surveillance capitalism, voyeurism and post-colonial exploitation. Is this to be seen or understood as a form of artistic resistance?

I certainly hope so! There is a long artistic and activist tradition of using the things, labels or tools suppressing you in favour of a subversive gesture. I don’t believe in a version of art saving societies by itself alone from the grave injustices they have been built on, and that’s also not the real task of an artist. But I feel that, even though the ‘memes’ as send out by alt-right movements are hijacking humour and can be understood as an attempt to bend irony towards neo-fascist messages, I still see irony as the most effective means to open space for potentially hurtful conversations that need to be stimulated in our society.