Lu Yufan (b.1991, China) is a writer and photographer currently based in Beijing and Tianjin. She graduated with an MA in Photography and Urban Cultures at Goldsmiths in London, where she acquired skills in combining photography practice with academic research.

Since 2018, Lu is doing research on the topic of the Chinese plastic surgery industry. In the last 20 years, the number of performed plastic surgeries plummeted in the country. The facial interventions are particularly popular among females below the age of 30. Intrigued by the facts and rising social pressure, Lu decided to photographically explore this phenomenon – both the thought processes of patients and surgeons.

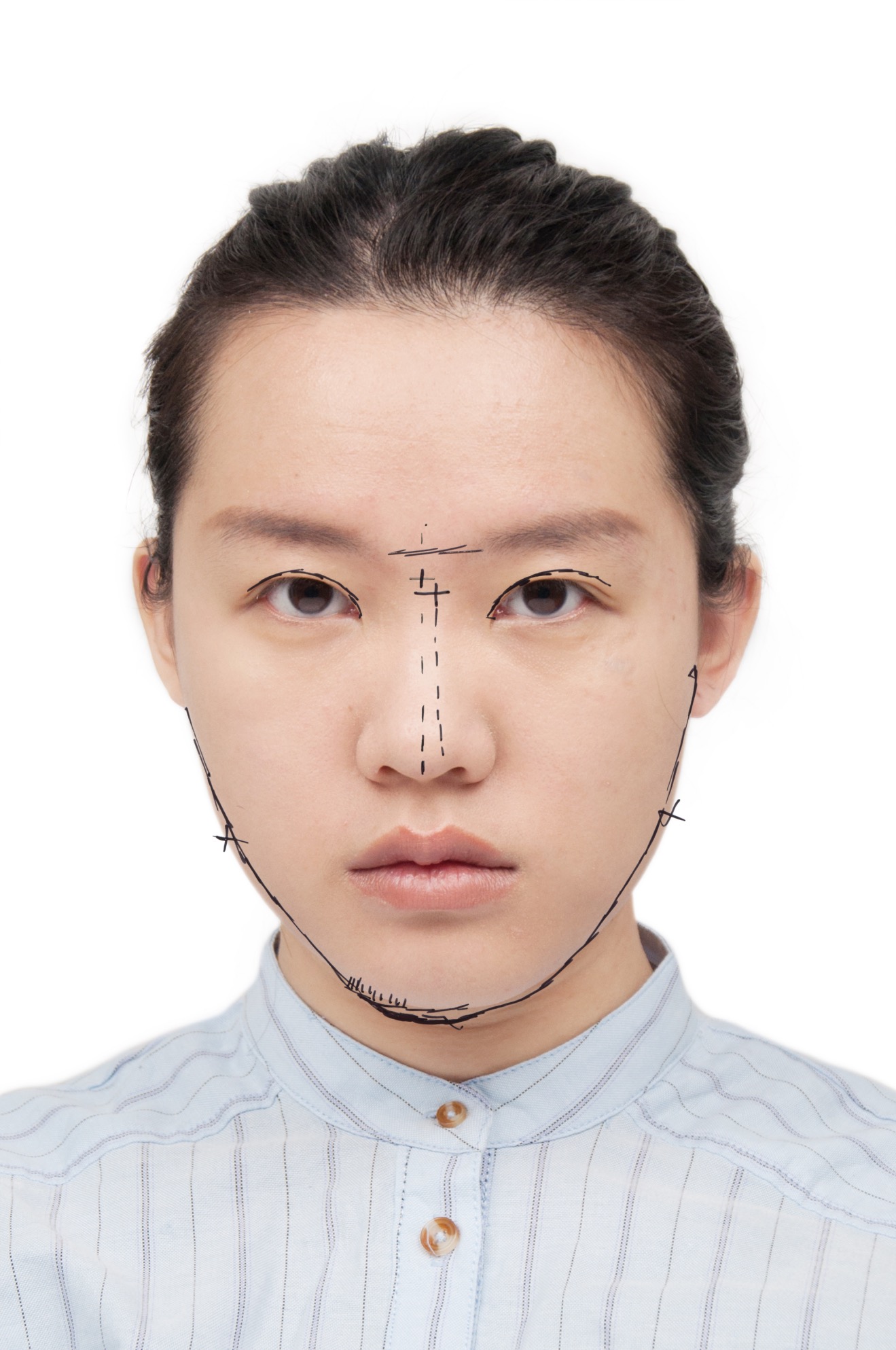

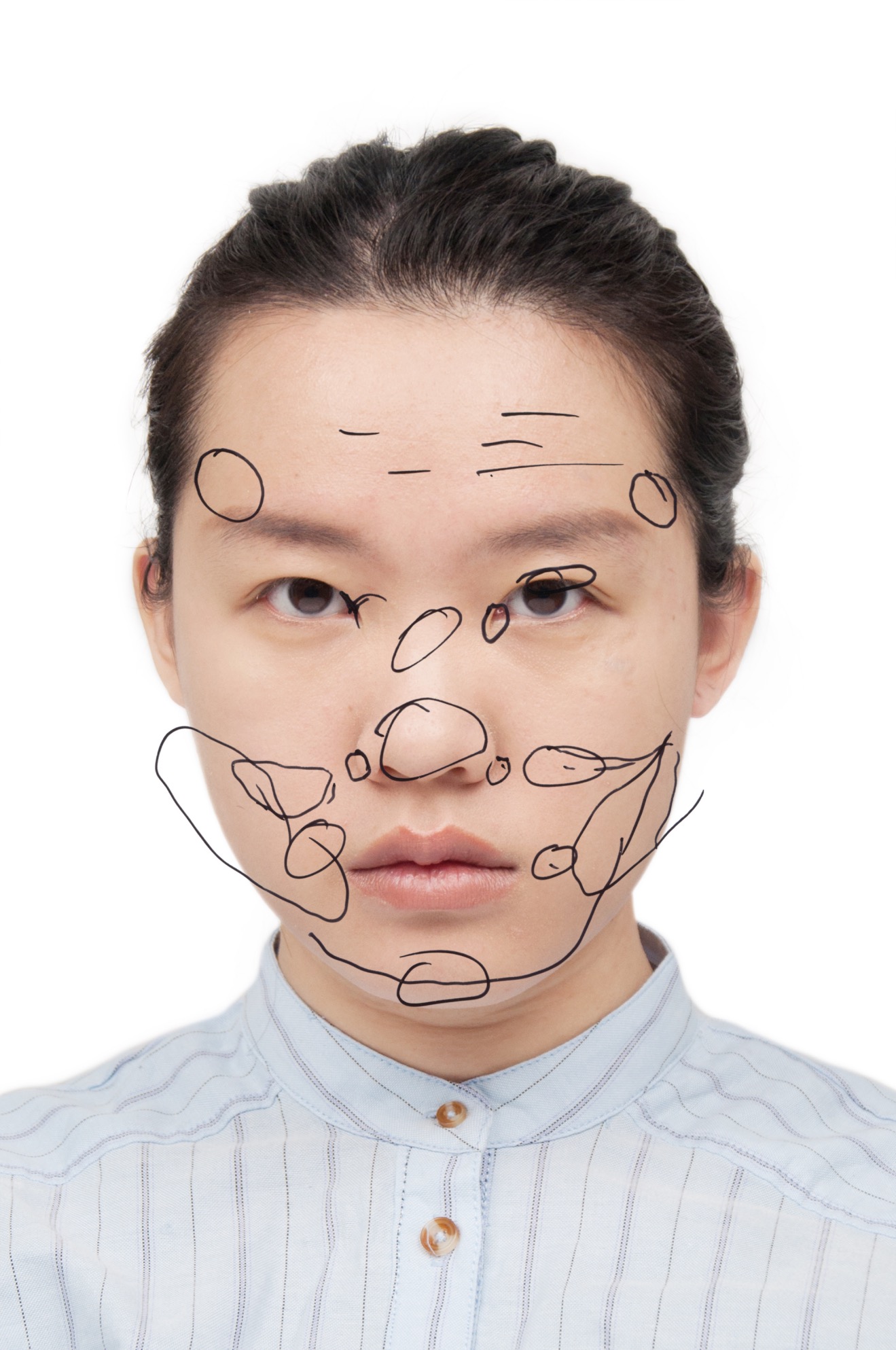

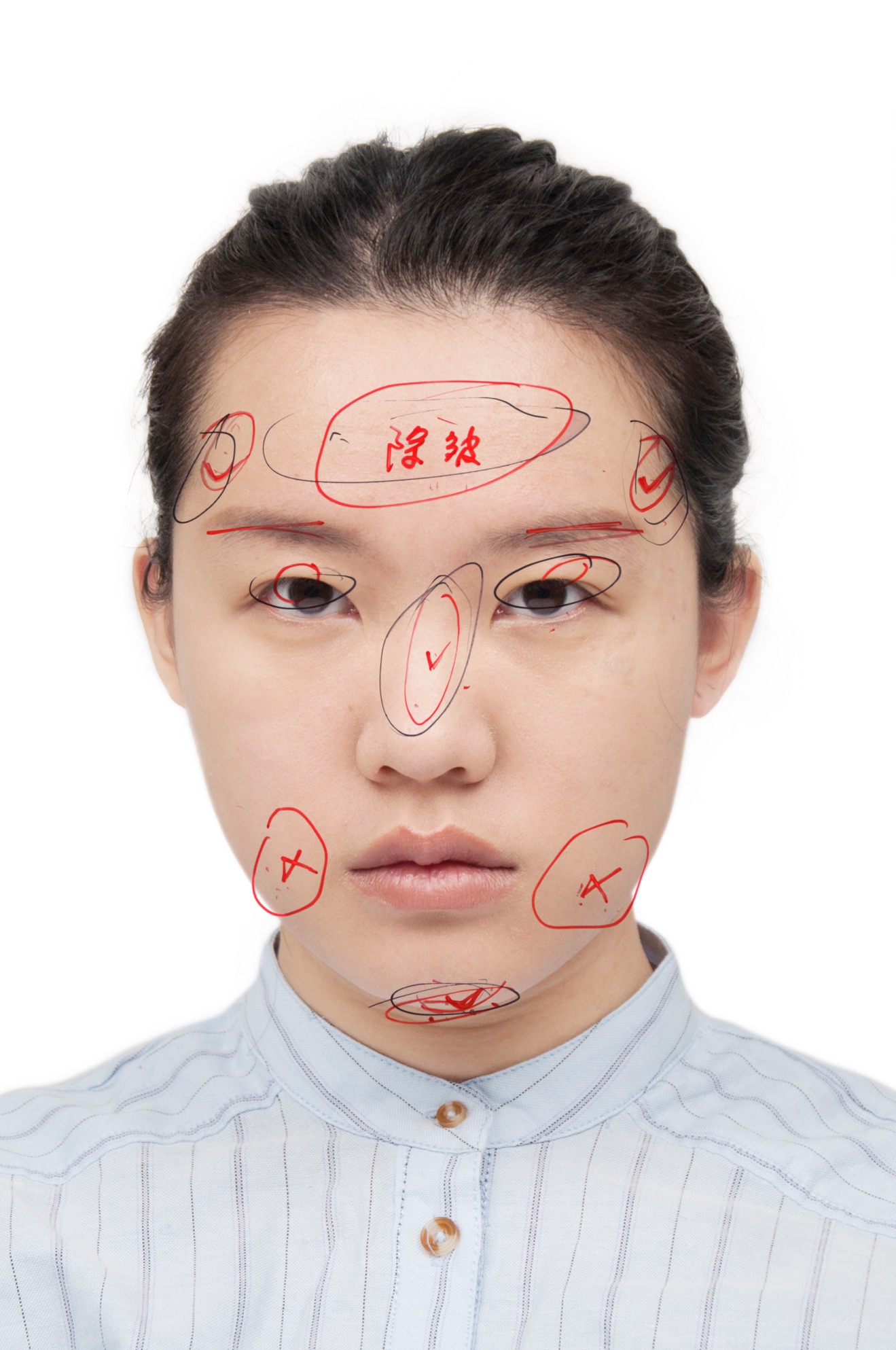

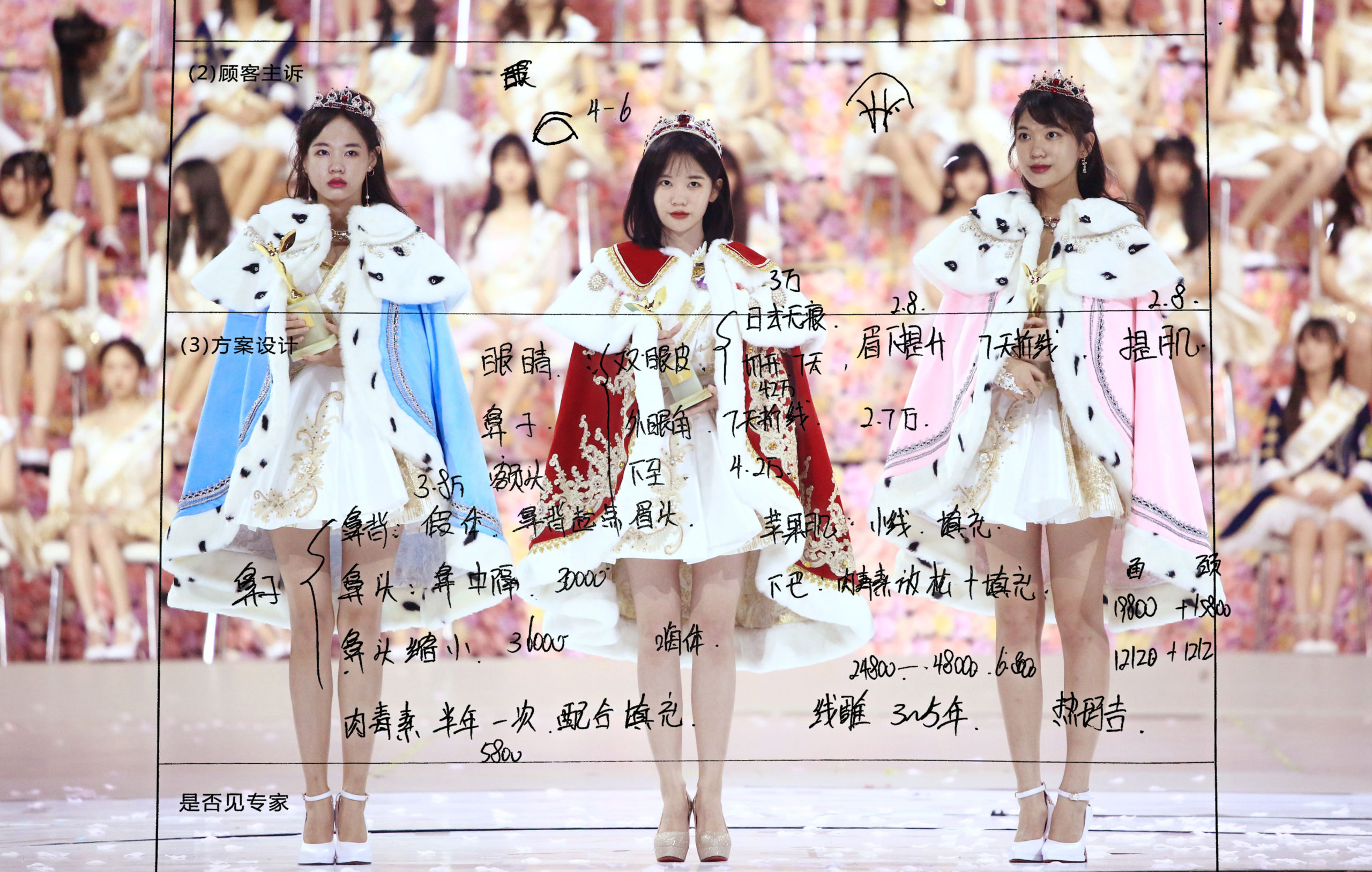

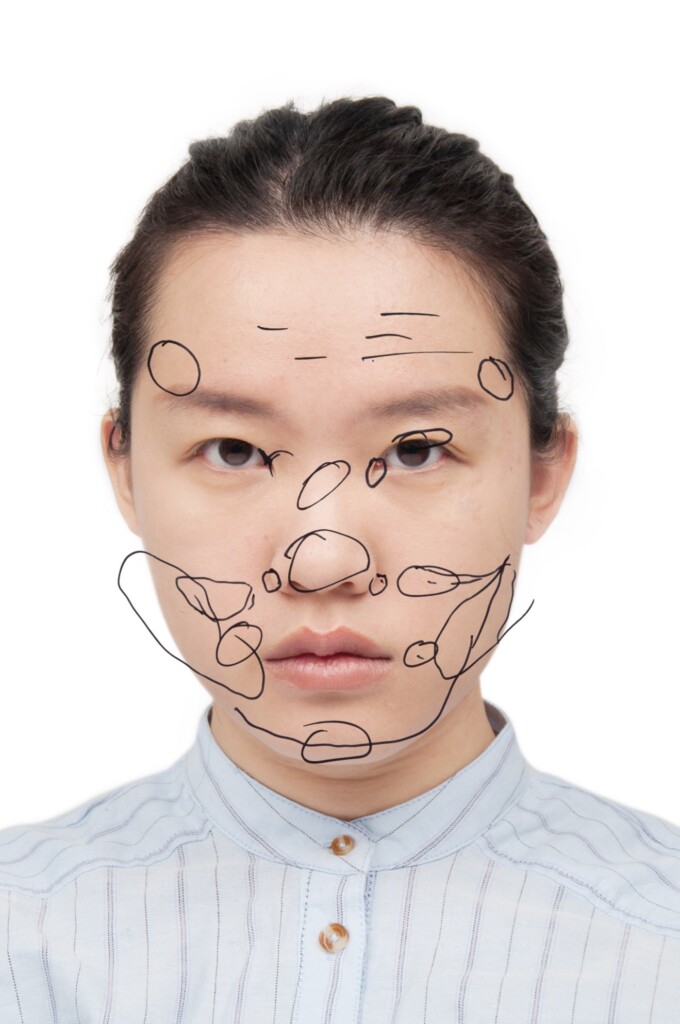

The series consists of both annotated self-portraits and portraits of people who already underwent cosmetic surgery that Lu found on the cosmetic surgery websites. In an interview with GUP, Lu talks about the context of her project and her way of working as an artist.

How did you start the process of creating ‘Make Me Beautiful’?

It started with my impulse to bring my portrait to the cosmetic surgeons and see how they will comment on my face. I intended it as a photographic project, but I also personally desired to know how my appearance would be judged by the people who represent the “beauty standard” in China. That said, I think I already had some answers in mind before I started the process. Growing up among the gaze from peers, relatives and strangers, I built my self-recognition mostly from other people’s comments – a great part of them was about face. Those comments are internalized and accompany me every time when I look into the mirror. Letting cosmetic surgeons write on my face is an enhanced version of those comments. I think I was also intending the project as an experiment – I want to see how I will recognize myself after intentionally facing myself with these scary comments about my appearance.

You sent your self-portraits to different cosmetic surgeons. How did it make you feel when you received the annotated photos back?

Many annotations are similar to each other – I can’t say I was surprised by the results. It only offers a visual proof that there exists an overarching beauty standard. But there are some diagnoses that surprised me. Other than pointing out my “defects”, some surgeons volunteered to offer me different solutions according to my preference. I could choose from the most popular types of faces, such as innocent and pure style, Internet celebrity style, high-level style – a type of face owned mostly by top models, etc. Although most surgeons told me I could only make changes based on my own conditions, there were also surgeons promising me that I can become whatever I like, as long as I’m willing to have several courses of operations. It feels the same as choosing products on a shelf. I could sense my weakness in front of the overwhelming consumerist culture.

What would you say is the role of text in the project?

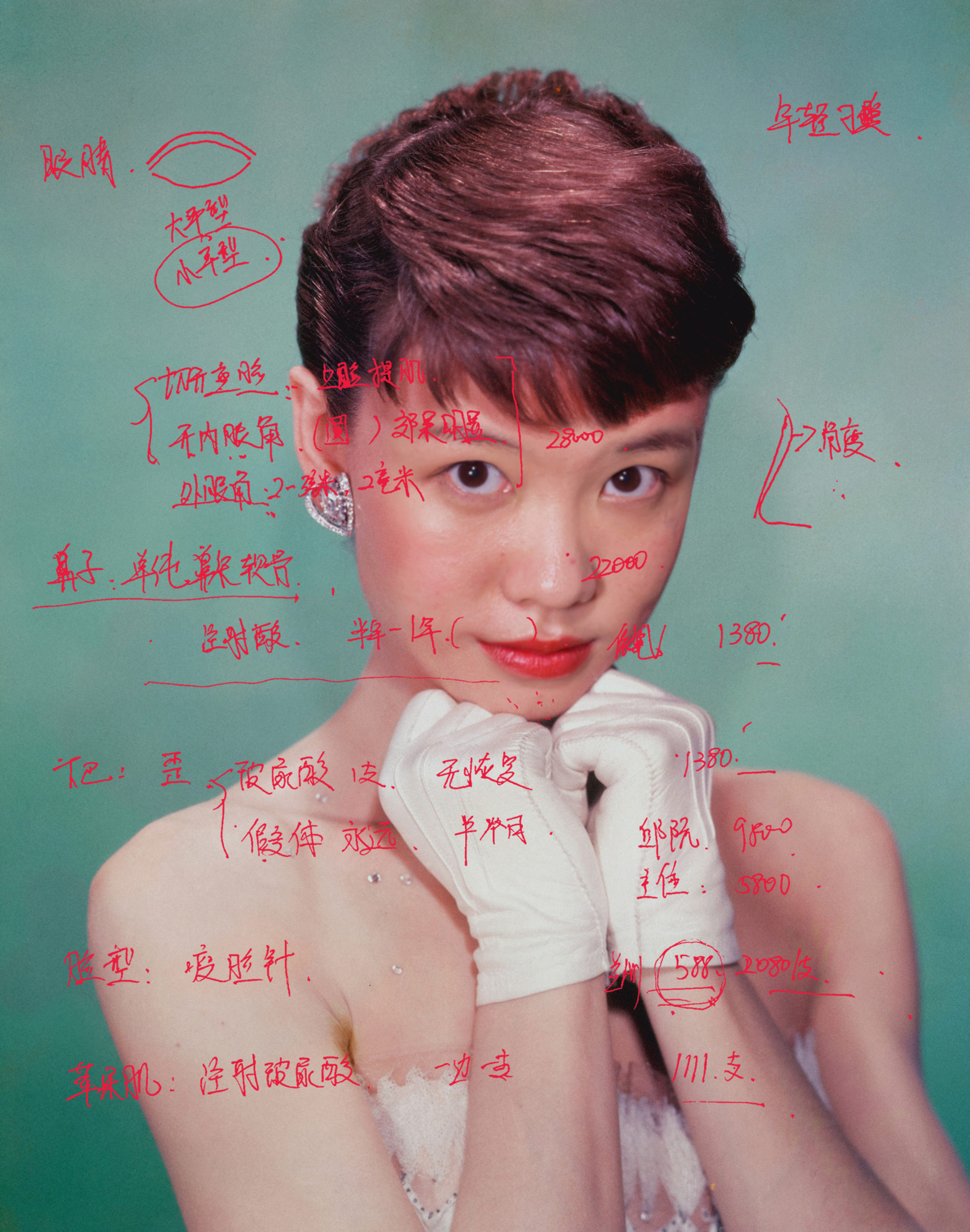

I matched hand-written text (written by people who have had cosmetic surgeries, or text faked by cosmetic surgery clinics in the disguise of people’s thoughts in my own handwriting) with the pre-surgery portraits of people who had done the surgeries. On the one hand, I think by doing that I was showing my empathy for them. Or it’s more accurate to say that I’m one of them. The only difference is that I didn’t undergo the surgery after putting myself through the diagnoses. On the other hand, I think the portraits taken by hospitals and my handwritten text form a contrast with my self-portraits and text written by surgeons.

I was also thinking of making a photobook while working on the project. That’s why I think the way the images and text are bound in the pre-surgery portrait part may not work that well in exhibitions but would work in a photobook.

“(…) It feels the same as choosing products on a shelf.”

In the series, you additionally include portraits of women that have carved out patterns on their face. What was your intention with this visual strategy?

These portraits are pre-surgery photos of people who already underwent cosmetic surgeries. When I first saw the portraits on cosmetic surgery websites, I was almost instantly drawn by the richness of the faces. Although, there were watermarks all over the portraits added by the website, and despite that these photos were taken by the surgery usually right before they entered the operation room as cold, medical evidence, I could tell the complex emotions on these faces: hope, insecurity, determination, farewell, secret…Of course they have so many things to say, because a moment after the photo was taken they were going to say goodbye to the face, and even the identity and memories attached to that face. I think those are really, really sad photos. And I think people who decide to undergo cosmetic surgeries are very brave. I know some of them are teenagers who were originally afraid of even having injections; some borrowed money to do the surgeries; some decided to do the surgeries anyway despite that they did thorough research in advance and knew about the risks they were going to face. And it makes me think: what makes people still go for cosmetic surgeries so firmly despite all these obstacles?

The portraits also remind me of post-mortem photos and even all the photos – the moment they are being made suggests the past and the lost. I guess I just really want to restore the portraits to their original look. So, I removed the watermarks. But I also want to reflect the pains that they are about to go through, and the insecurity about appearance that stays the same after the surgeries, so I tried to keep their original look despite carving out patterns on them.

“(…) I could tell the complex emotions on these faces: hope, insecurity, determination, farewell, secret…”

What were the reactions you received in response to ‘Make Me Beautiful’? And what do you think are the ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ in addressing this subject matter?

A distant friend came to me after she saw the work and told me that she recognised herself in my portraits. She also had the experience of visiting different cosmetic surgeries trying to find anti-aging solutions. I was surprised but also very grateful to hear her sharing this experience with me because usually, people tend to keep it a secret. Also, since I did the project mostly from my own perspective, I didn’t have much chance to know if my experience is universal except from other people’s responses.

I think such subject matter can be very tricky because it involves intertwining power structures between the gazer and the object of the gaze, both existing in the visual culture behind cosmetic surgery and in the photographic practice. In my case, I was standing along with the people who have undergone cosmetic surgeries from the beginning and put myself under the gaze instead of in the position of the gazer – or to put it more accurately, I was mixing the two roles via selfie. This special standpoint naturally obliges me to consider the sensitivities involved in the issue. I think it’s important not to objectify the subjects in visual representation, especially when the cosmetic surgery they have undergone is already a kind of self-objectification. I also try not to show my attitude towards cosmetic surgery in the work, because I know a lot of people who are aware of the self-objectification involved in their recognition of themselves, and the risks of cosmetic surgeries, and still couldn’t help but go through them. I sense this helplessness in myself too.

Another issue that intrigues me is the ethics of portrait photography involved in this subject matter. I think many projects on cosmetic surgery involves the deformation of faces, virtual faces, algorithm-rendered faces that theoretically does not match any real subjects. But I don’t feel this grant the photographer immunity to do anything to the image. What matters here is not a specific face, but the issues behind the face that everyone is confronted with.

“(…) I think it’s important not to objectify the subjects in visual representation, especially when the cosmetic surgery they have undergone is already a kind of self-objectification.”

In ‘Make Me Beautiful’, you are personally involved while pointing to an issue that is universal. What has this project brought to you and what do you still aim to achieve with it?

The project unexpectedly developed into a kind of therapy for me. I feel it’s as if I separated the part of me who is unconfident about my appearance from the part of me who used the less personal, objective photographic eye to observe the journey of an unconfident person seeking cosmetic surgery solutions. When I look into the mirror now, I feel that I’m looking at myself from the two perspectives, and it helps me to keep some distance with my low self-esteem. And I do hope this flickering reversion of power structures could empower people who have a similar experience.