Cemre Yeşil Gönenli (b.1987, Turkey) is an Istanbul-based photographer, artist and visual storyteller. In her recently published book ‘Hayal & Hakikat’ (translating into Dream & Fact), Gönenli presents cropped images of prisoners’ hands found in the photo albums of Abdul Hamid II, the 34th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.

The Sultan had an interest in the medium of photography as it could serve as a proof of the Ottoman Empire’s modernisation at the start of the 20th century. Abdul Hamid II even built his own photo studio in the Yıldız Palace and frequently sent out photo albums abroad as a statement of progress.

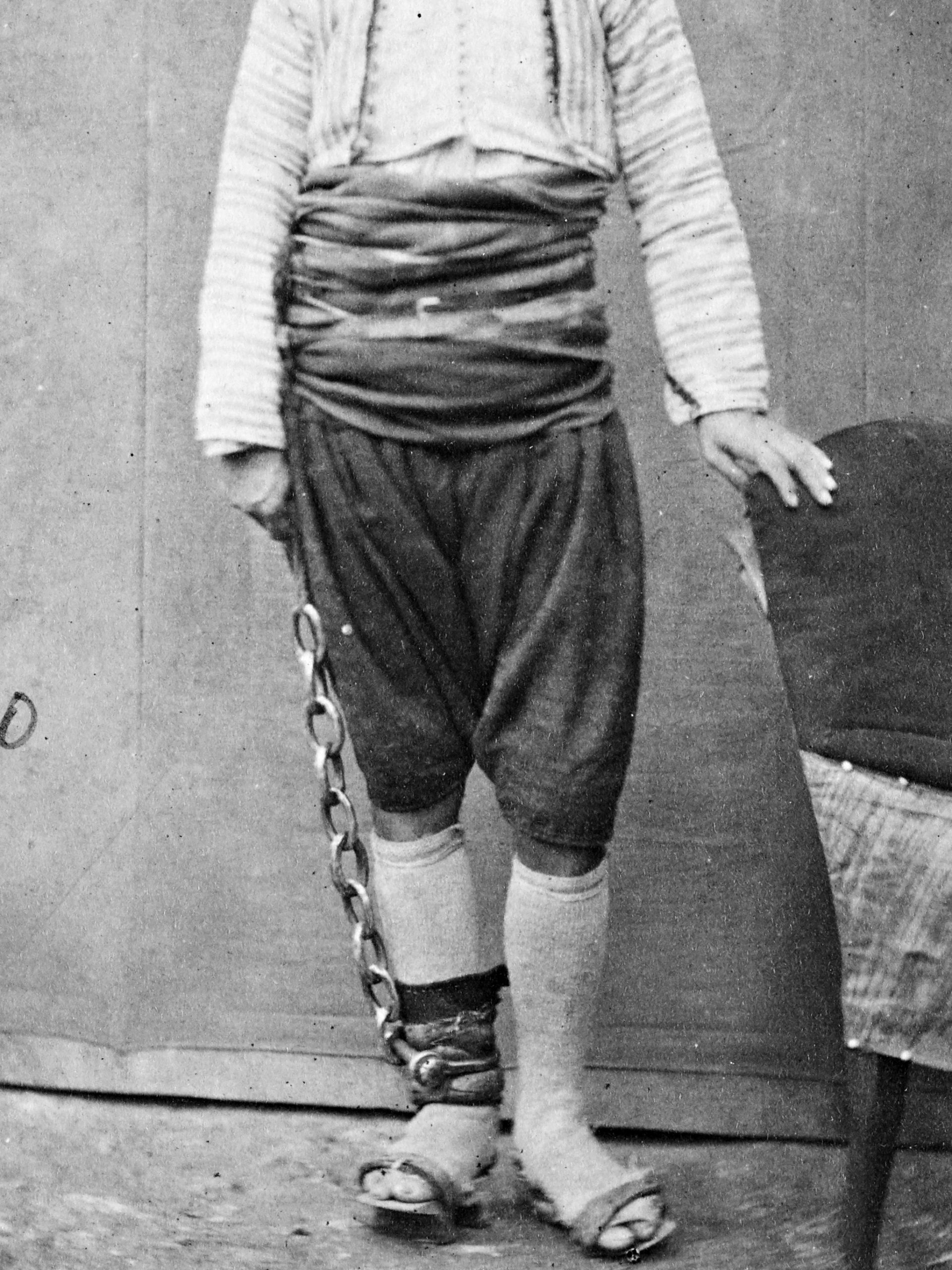

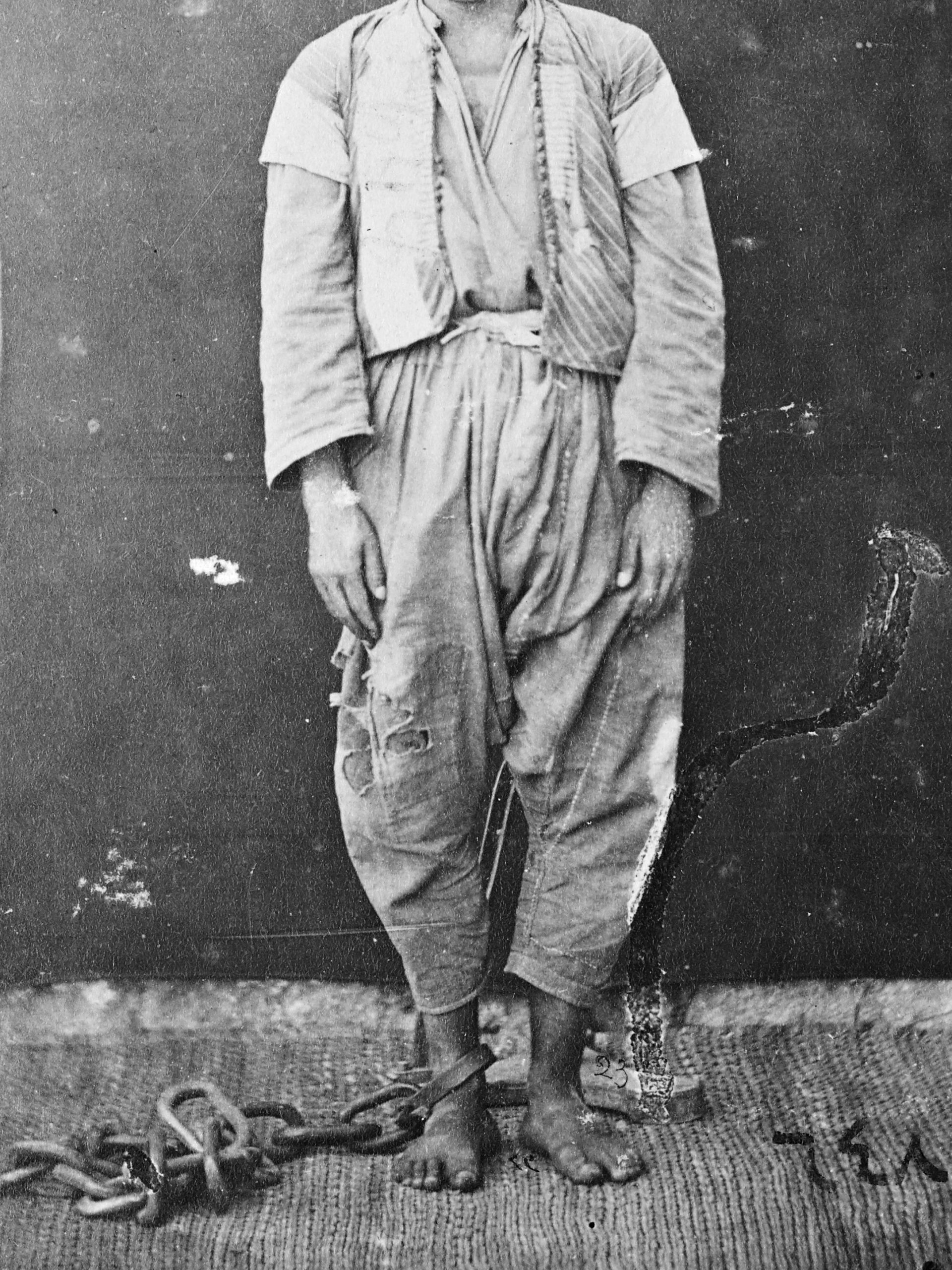

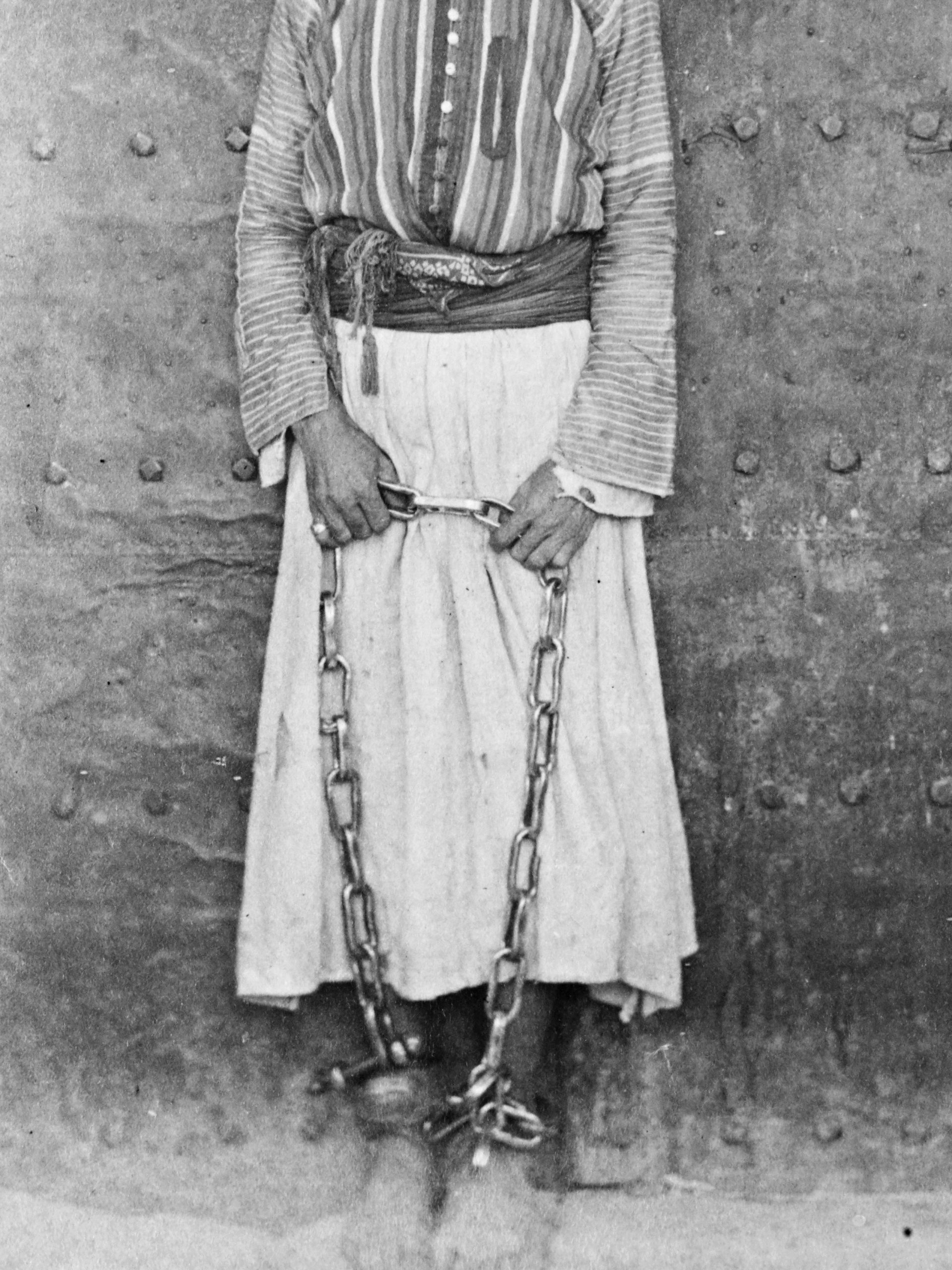

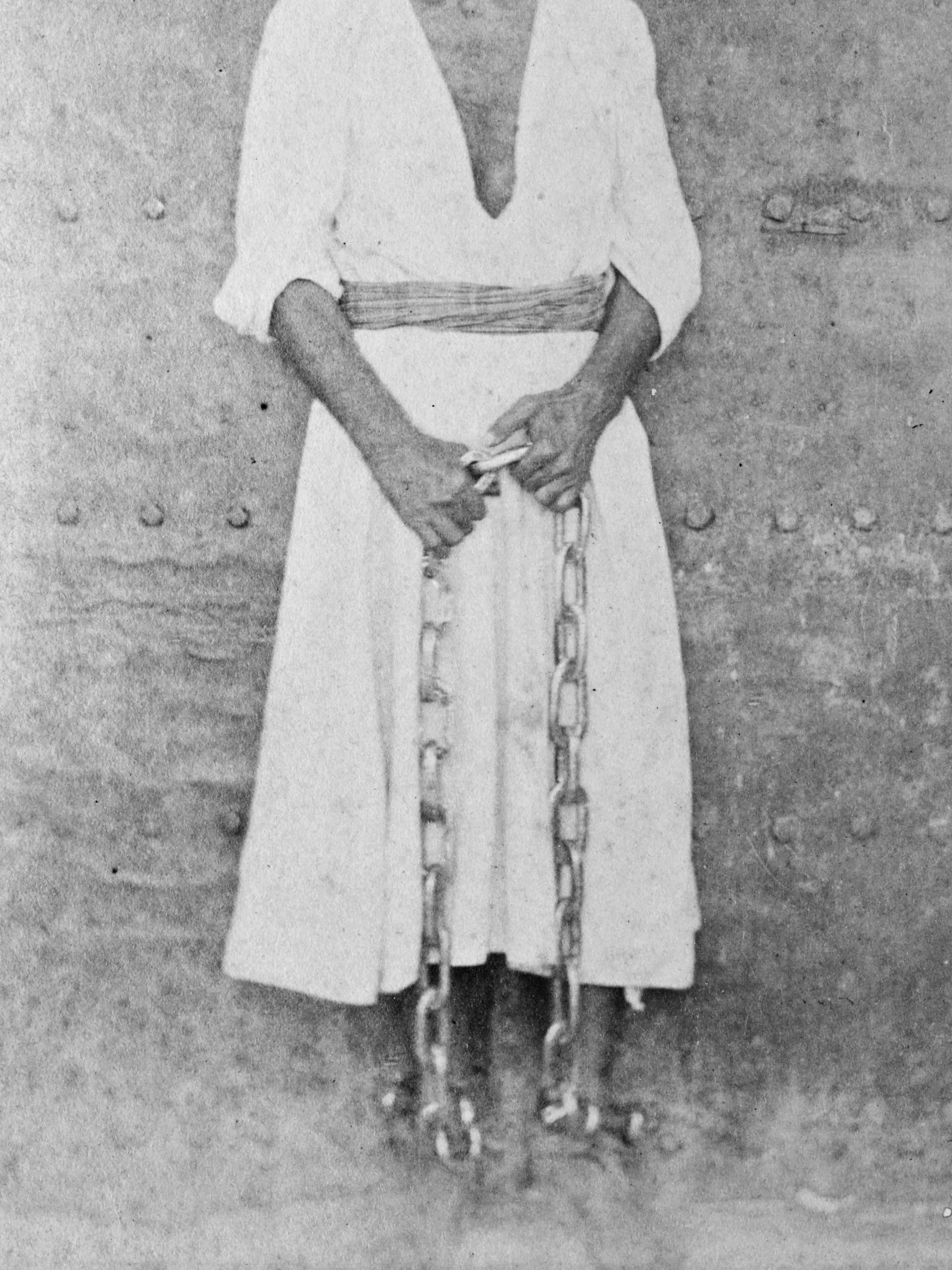

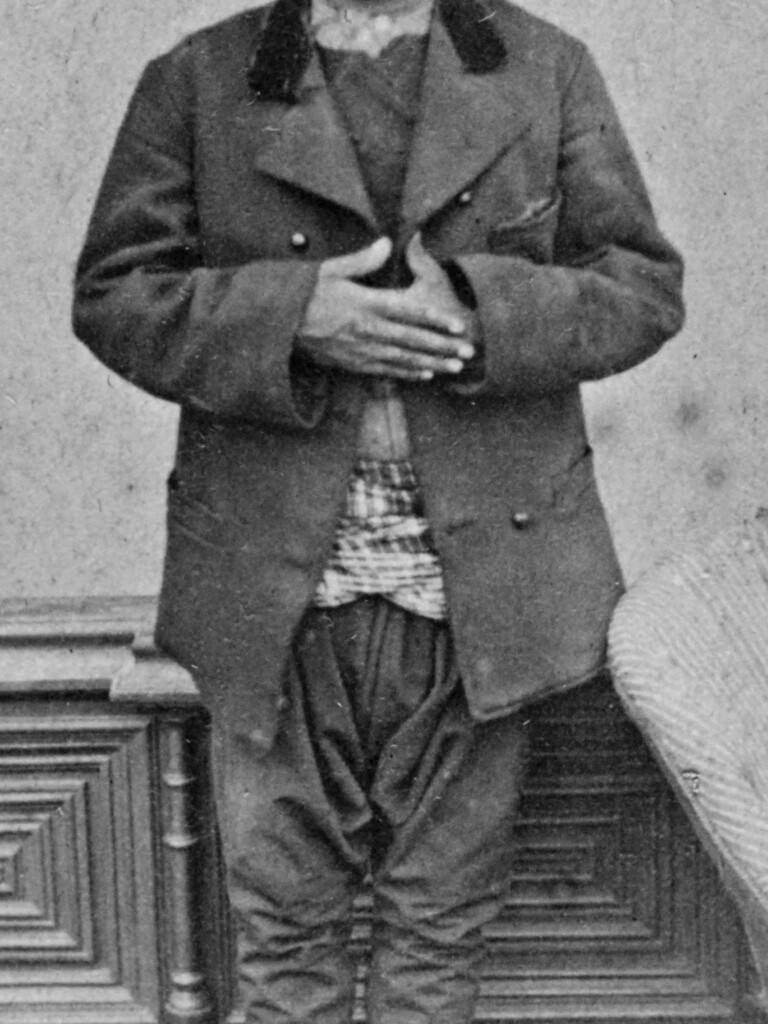

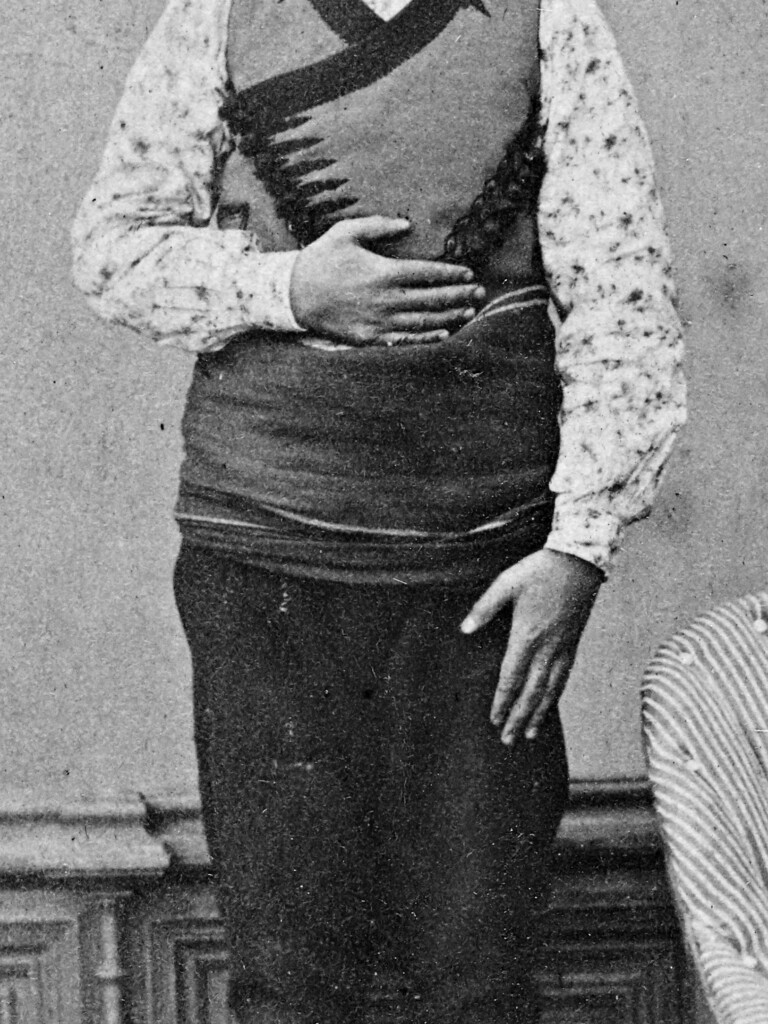

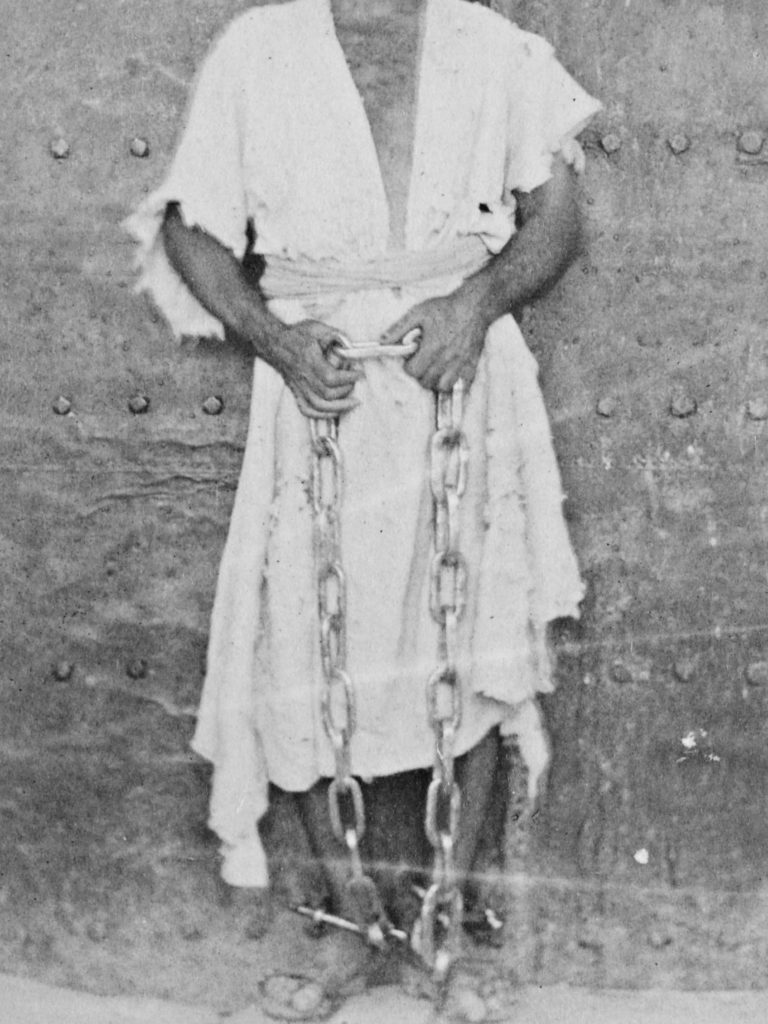

Besides that, during the 25th year of his reign, he ordered all murder convicts to be photographed with their hands visible because he was planning an amnesty. Inspired by a crime novel he read, he decided to judge the prisoners based on one characteristic: their thumb joint should not be beyond the index finger – as he thought that people with such a feature are more inclined to murder than others.

Gönenli decided to restate an interest in this fascinating history, if only to question certain mechanisms of power. In an interview with GUP, she reveals the process of creating ‘Hayal & Hakikat’ and points out its contemporary relevance.

How did you come across Abdul Hamid II’s archive?

The book was created during a workshop: ‘Interpreting the Encyclopaedia of Istanbul with Photographs’, organised by Geniş Açı Project Office and SALT in May 2019. The project was about gathering all the research materials that comprise the encyclopaedia of Istanbul, which was established in the years between 1944-1973 by Reşat Ekrem Koçu.

Yet, it doesn’t really function as an encyclopaedia as it was very subjective. Koçu wrote it in a way to reflect his understanding of the city, featuring his personal anecdotes as well as some fictional characters. Consequently, as a reader, you cannot really distinguish between what is real and what is fiction.

For the photography workshop ‘Interpreting the Encyclopaedia of Istanbul with Photographs’, I was assigned (alongside two other artists) to produce a body of work departing from one of the entries in the encyclopaedia and later lead a workshop for other participants.

We had only a limited amount of time, about three weeks to complete this project. Hence, I quickly flipped through the book because it was impossible to read it all. After a while, I instinctively went to the word “fotoğraf,” meaning a “photograph” in Turkish. In that section, I found an intriguing piece of information where Koçu stated: “On the 25th anniversary of the reign of Abdul Hamid ll, he wanted to make an amnesty, but he would choose himself who to free – based on the detainees’ photographs.”

I immediately started to question: how it is possible to make such an important decision just on the basis of a photograph?

I went to Istanbul University ‘Rare Items’ library and there, I found the archive I was looking for. I was really stunned by the pictures of the prisoners and immediately realized there was something going on with their hands. They were very much exposed, and it was not really a natural way of posing.

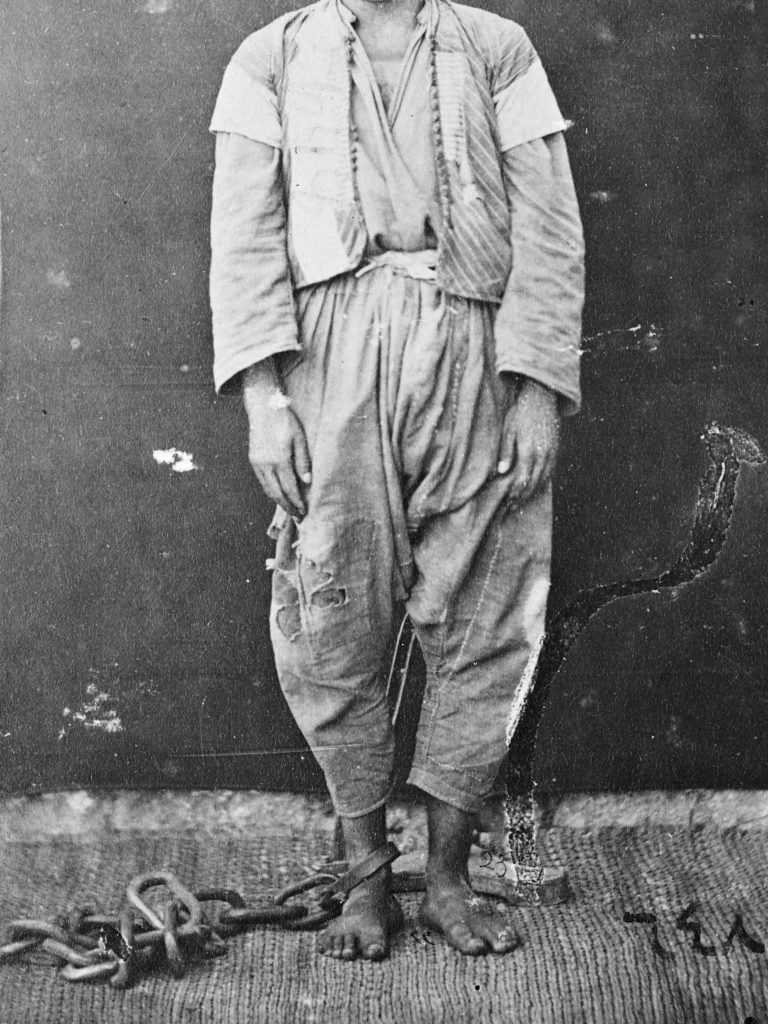

I have been attracted to photographs of hands for a long time, so they were a clear trigger for me. In the archive, I also found another collection of photographs displaying prisoners that had iron bracelets around their body parts which I also took home with me.

However, in the books, all annotations were in the old Ottoman Turkish language which I couldn’t understand. So, I had to research further and eventually managed to find a historian Prof. Dr. Melek Özyetgin who is an expert on Abdul Hamid II. She enlightened me and said he was very much interested in science fiction and crime-fiction theories. She also told me that she doesn’t know the source of the information but apparently, Abdul Hamid II believed that any criminal with a thumb joint being longer than that of the index finger joint, is more likely to commit a crime or kill someone.

Why did you decide to crop the heads of the detainees?

As a viewer, I didn’t even look at the prisoners’ faces. For me, it was all about their hands and I thought it would be way stronger to have their bodies speak for themselves than looking at their facial expressions. I didn’t want to portray them as criminals but symbolically give them a second chance in life and, perhaps, also their freedom. Although this was a brutal gesture, I justify it as a way to save and forgive them.

“I didn’t want to portray them as criminals but symbolically give them a second chance in life (…)”

Could you please explain the meaning behind the title ‘Hayal & Hakikat’?

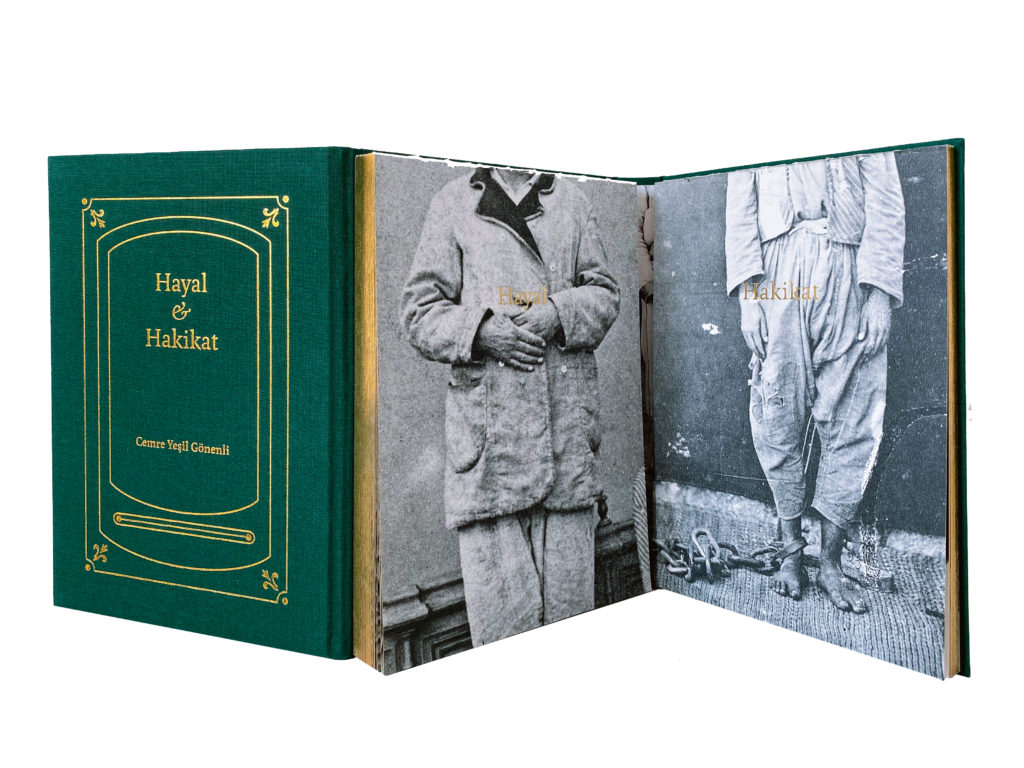

“Hayal” means “dream” and “Hakikat” means “the fact” in Turkish. With the title, I wanted to emphasize this clash between the people who are waiting for forgiveness with the images of heavily chained prisoners who do not have any chance to be free again. The chained prisoners were all sentenced to death as was revealed in the archive.

Therefore, the viewer sees this conflict between two different types of imagery. One side captures those that are going to be imprisoned for the rest of their lives whereas the other shows a glimpse of hope for the portrayed people who were perhaps freed due to the amnesty.

‘Hayal & Hakikat’ is divided into two booklets: ‘A Handbook of Forgiveness’ & ‘A Handbook of Punishment’. What were the main editing decisions when making the book and what is the ideal way to browse through it?

It was designed more or less as a didactic book so that the reader would just flip through it in a fast way. I made this choice based on the process of how the decision about their fate was made by Abdul Hamid II. Also, I show the two booklets in a physical way – one representing the dream and the other the fact – to collide into each other when closing the book. But at the same time, they are symbiotic.

By making this book, I had many thoughts about punishment and forgiveness in an abstract way and I hope that the reader can feel and experience it in a similar manner.

There is an underlining sense of repetition in the book but at the same time, one is triggered to search for details in each photograph. What role does repetition play in the publication?

Repetition is, indeed, a huge part of it. As I said, first, the readers are led to browse through the book quickly and once they become aware of the context then they are supposed to slow down and start to look at the images again. For instance, one image contains a large fingerprint of the person who processed the film. Then, regardless of the repetition, all images become unique through their individual details.

By questioning the authority of Abdul Hamid II, do you consider your publication as a form of protest?

‘Hayal & Hakikat’ re-contextualizes the archival images so that they would make a statement about the present. The whole process of making the book very much resonated with the general question of who is free and who is not.

The absurdity of decision-making, for me, mirrored the political climate in Turkey today.

A friend of mine with whom I was teaching at the same university, was sent to prison. Out of nowhere! I know that he is a good-hearted and intelligent person, he was one of us. No one actually knew the official accusation. He himself didn’t even know what he was charged for.

Him being locked down in prison became one of my motivations for making ‘Hayal & Hakikat’. This situation really touched me and for some reason, I felt that now this could happen to anyone. Many journalists, artists and intellectuals were recently jailed or deported from the country.

Speaking from my own experience, I would not define myself as a politically active person. However, in 2013, there was a wave of protests in Turkey (Gezi Park protests) and that was the only event that we, as a younger generation, engaged in. We were just trying to protect a small park in the middle of the city. This whole thing turned into a massive event and for a short period of time we believed that we were able to change some things for the better, but nothing happened. It was a huge disappointment in the end.

After this happened, I completely lost my motivation to go out protesting in the streets, it all suddenly became pointless. If you say something and then you are being teargassed, it’s not worth the pain. In this way, ‘Hayal and Hakikat’ is my way of a silent protest by trying to state that something is going wrong in today’s Turkey.

“‘Hayal and Hakikat’ is my way of a silent protest by trying to state that something is going wrong in today’s Turkey.”

‘Hayal and Hakikat’ is co-published by GOST and FiLBooks and was recently shortlisted for Aperture’s 2020 PhotoBook Awards. It additionally contains an essay by Refik Akyüz (translated by Orhan Cem Çetin). The publication can be purchased here.